Kelly is a former librarian and a long-time blogger at STACKED. She's the editor/author of (DON'T) CALL ME CRAZY: 33 VOICES START THE CONVERSATION ABOUT MENTAL HEALTH and the editor/author of HERE WE ARE: FEMINISM FOR THE REAL WORLD. Her next book, BODY TALK, will publish in Fall 2020. Follow her on Instagram @heykellyjensen.

Jamie: Regulation 43.170 was created by the SC State Board of Education and automatically went into effect August 1, 2024, after it failed to receive a vote in the SC General Assembly. It establishes a pathway for citizens to appeal a school district’s review committee decision directly to the SC State Board of Education. The Instructional Materials Review Committee (IMRC), comprised of 5 members of the state board, receives submitted complaints and votes to recommend retention, restriction, or banning. The full State Board then votes to adopt the IMRC’s recommendation, thus establishing a way to ban books (and any other instructional materials) from every public school in the entire state. Local school districts can also choose not to consider locally-submitted complaints and instead send those directly to the IMRC for consideration. (This option is described in very positive language, as if the state board is helping districts lessen their work loads by removing the local democratic process.)

There are a few crucial components of the regulation that are important for people to be aware of. The regulation only concerns what it attempts to define as age inappropriate sexual conduct, which directly conflicts with SC obscenity law (16-15-305). It also does not provide any consideration for the variations in appropriateness between a kindergarten student and a high school senior. The IMRC does not require itself to read the challenged work in its entirety. Rather, it relies on excerpts and other information provided by the complainant. As such, the work as a whole is not considered, so there can be no exceptions made for literary merit. However, SC Code of Law 16-15-305 does allow for literary merit to be considered. In this way, the IMRC and state board of education can ban a book from every public school in the state simply because of one phrase. We are still confused why this regulation can be implemented while simultaneously conflicting with established state law.

The “need” for this regulation was manufactured by SC Superintendent of Education Ellen Weaver (who has direct, public ties to Moms 4 Liberty) under the guise of an absence of a “uniform process for local school boards to review and hold public hearings on complaints raised within its district.” In other words, supporters of the regulation didn’t like that local school districts have control over which instructional materials are available in school libraries, so they dubbed this local control as “confusing” since districts may have different local policies and procedures. It’s important to note that the impetus for this regulation originated with Ellen Weaver and her outside legal counsel with ties to the Federalist Society (who was paid over $40,000 of taxpayer money), not the SC State Board of Education.

Many people are aware of the 97 books challenged in Beaufort County in 2022, which after much time and thousands of dollars, the review committees ultimately returned all but 5 of those titles to school library shelves. The people who supported banning those 97 books decried that decision as undemocratic simply because they didn’t get their way, even calling the review committees “biased” because they were comprised of more educators than parents. The result is that now, book challenges are considered by only five members of the state board of education who do not read the books.

Where and how has the South Carolina Association of School Libraries been involved in pushing back against this law? What other on-the-ground groups or organizations have you been collaborating or allying with?

Jamie: Statewide anti-censorship efforts began in 2021 when Governor Henry McMaster tasked then-SC Superintendent of Education Molly Spearman to “investigate” how a book like Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe could end up in South Carolina public school libraries. South Carolina Association of School Librarians (SCASL) leaders were invited to collaborate with Spearman to develop a model school library selection and reconsideration policy that districts could choose to use to ensure they had a policy in place. We were pleased with this result and grateful for the collaborative opportunity. However, other challenges were rapidly popping up across the state.

In October 2022, SCASL President Tamara Cox and Josh Malkin from the ACLU recognized a need to bring together various organizations and groups with similar goals across the state. They started the Freedom to Read SC coalition with the goal “to defeat unconstitutional efforts to ban books from school and public libraries.” Of course our challenges aren’t just restricted to book banning, but broader issues such as defending students’ rights, public education, and the rights of all parents. Creating a statewide coalition allowed for parents, religious leaders, community organizations, and other local decision makers to network and to support each other, particularly when censorship continues to happen at the local level and in differing ways.

SCASL also showed up as an organization during the 2023-2024 year when the state board was creating the regulation and were part of efforts to get some key amendments added before the final version was passed, and we’re very proud of that. Initially, the regulation was much more restrictive and damaging. There were no restrictions on the number of challenges a person could submit each month, and any citizen could submit a challenge as opposed to only parents/guardians with students in the school district. The original proposed form also would have banned any instructional materials containing words which would be censored on broadcast television. We spent so much time attending state board meetings and writing letters as did our partner organizations and countless concerned citizens.

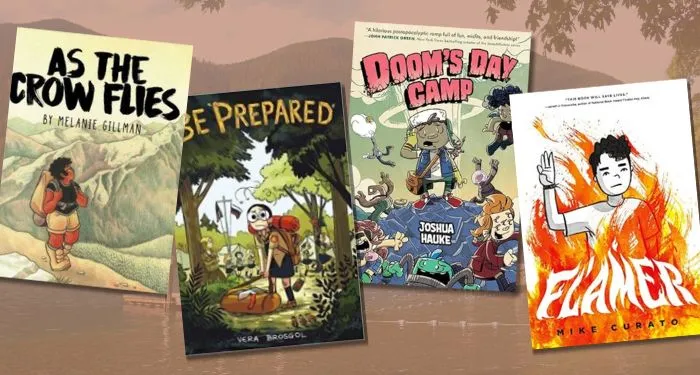

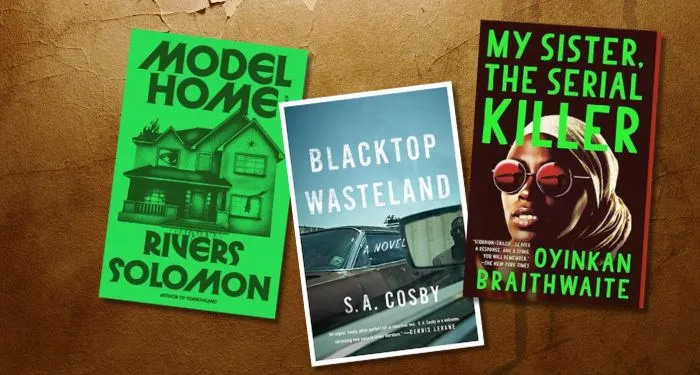

SCASL was proud to partner with Freedom to Read SC this year to begin a virtual book club which was open to any SC citizen who wanted to learn more about book censorship. We read two books which were banned by the state board this year, Flamer by Mike Curato and Last Night at the Telegraph Club by Malinda Lo. Curato was also a featured author at the Read Freely Fest which was hosted by the Richland County Library in Columbia, SC. This type of advocacy seeks to provide folks with the opportunity to learn more about the targeted books and authors. In other words, as professional school librarians, we know that providing education is the key to combating censorship.

Tenley: Several grassroots organizations have formed to oppose the censorship being imposed by the State Board of Education. We do not coordinate their efforts, but we appreciate their support.

Something that’s been impossible to not see is that there is a big difference in response to book censorship and attacks on libraries from state library association to state library association. Why is there such a difference? As folks in a state where censorship and attacks are among the highest in the country, it has to be frustrating to not see that same level of engagement–proactive anti-censorship advocacy included–mirrored in every state-level association.

Jamie: I think it just comes down to the volunteers who are part of each state school library organization. Yes, we are all volunteers! The members of our board all work full-time jobs in addition to fulfilling their SCASL board duties. I initially accepted the offer of SCASL leadership back in the fall of 2022 before anyone knew this regulation was on the horizon. Now, people are agreeing to volunteer with the full knowledge of the deep level of opposition we’re facing, and it’s not for everyone. We interact with people who are ideologically opposed to the very idea of what we do as a profession, who have publicly cut ties with our organization, who have publicly attacked us professionally and personally. Many school librarians can’t be as involved as they’d like to be because they rightfully fear retaliation from their school districts and communities. It’s simply not easy work.

We’ve also faced even more opposition in South Carolina because at the very beginning of Ellen Weaver’s tenure in 2023, she abruptly decided to sever ties with SCASL, effectively ending what was a 50-year partnership between SCASL and the SC Department of Education. She utilized her political positioning to publicly attack our organization which has more than 1,000 members statewide, which has simultaneously encouraged some of us to become even more involved in fighting back but also difficult for some because of her position and influence.

The same strategies are also not necessarily going to work in each state because each state legislature and state board of education can function differently. At the same time, some state superintendents of education are connected through their national political groups and other ties, such as South Carolina and Oklahoma, so it would be beneficial to have stronger ties across states. Another obstacle we face on that front is that of course the individuals serving in leadership roles change each year in our school library associations, making it difficult to achieve long-term collaboration.

But I am willing to bet that South Carolina is the foremost leader in intellectual freedom advocacy in the entire nation because of the extraordinary networks that have developed across the state since 2021. It’s all thanks to the efforts of a few individuals who have worked tirelessly to connect as many like-minded people as possible so that when an issue arises, the network can show up and speak out. We’ve had some victories in our state in individual school districts because of our state’s organized efforts, which has been so encouraging to watch especially this past year. I’m simply amazed at how many people in this state have become involved in this hard work and how willing they are to work as part of an organized movement. We inspire each other, we hold each other up, we know we don’t do this work alone; this camaraderie ensures the future strength and growth of our movement.

How has this law impacted school librarians? In what ways has it emboldened hate and harassment toward library workers?

Tenley: I recently spoke at an event that a grassroots organization hosted. Afterward, the local Moms 4 Liberty Group posted on Facebook that we had been discussing porn for kids. We also had a speaker at the April State Board of Education meeting make public comments calling librarians “porn pushers.” Certain individuals have found that they can make defaming or libelous statements with little to no consequences.

Jamie: People who support the regulation have started to use more targeted rhetoric against us. Some suggest that because we advocate against the regulation, we must support having sexually explicit materials in school libraries. Making audacious claims such as this is demoralizing and as Tenley said can cross the line to defamation. Some simply don’t think twice about accusing us of felonies such as distributing pornography to minors. Some of us have been publicly attacked by elected officials such as state representatives and senators, leading to people calling our schools and complaining about us, making us fear for our jobs.

We all know how easy it is for rumors to spread through social media. We’ve had school librarians who no longer feel welcome or even safe in their communities because of comments that have spread. That’s the kind of consequence that can’t be taken back or erased.

I think in general, it has caused a widespread feeling of disturbance that Superintendent Weaver and the state board are targeting our work when we in fact provide fundamental services to our students, teachers, and parents, including teaching people how to access information and use it safely and ethically, as well as teaching people to love reading in part by providing inclusive and diverse reading materials. That our profession can be reduced to simply whether or not we provide access to sexually explicit materials is frankly dumbfounding and confusing particularly when our state ranks toward the bottom in educational achievement. We know it’s a political talking point, but again, we’d rather not be the ones paying the price for someone’s political ambitions.

Where and how have you seen the law fuel quiet/silent/self censorship in school libraries? Do you have any sense of the scope of such censorship in school libraries?

Jamie: Quiet censorship is perhaps the most insidious side effect of this regulation (and of Ellen Weaver’s leadership more broadly). Members have reported to SCASL leadership throughout the year how individual school districts decided to broadly censor many books before the school year even started in an effort to avoid controversy. These actions are described as “quiet” because students and parents don’t even know it’s happening. When school librarians are given a list of titles and asked to remove them, they often don’t have much choice except to comply. Even though regulation 43.170 is limited to censoring materials for sexual content, many officials more broadly censored any materials it deemed potentially controversial, including on topics related to Black and BIPOC history and LGBTQ+ topics, which constitutes viewpoint discrimination.

Similarly, the type of environment created by Superintendent Ellen Weaver and regulation 43.170 causes some school librarians to deselect the purchase of materials that could be viewed as controversial, which is self censorship. We remind people that the regulation focuses solely on sexual content. We also relay the message that self censorship can be a form of simply trying to preserve one’s position, which is understandable. Sometimes school librarians are forced into these decisions; we are not trying to judge people who self censor. However, we try to encourage people to be mindful of their actions, not to interpret the regulation beyond what it actually states, and to have conversations with their school administrators to lessen the impacts of the paranoia and confusion caused by the regulation. We also advise school librarians to reach out to others in the community who can be more vocal on their behalf.

It was widely anticipated that the State Department of Education would ban 10 books in April, but that meeting, it sounded like several members of the committee were questioning what the point of such bans were–some going so far as to question why they were driving once a month across the state to do so. That shift in tone reversed in May, when those 10 books were then banned. What do you think it will take to see actual change going forward?

Jamie: I think it’s a victory in and of itself simply to have witnessed the discussion which took place during the April meeting. We were so heartened to hear a thoughtful, reflective discourse, but feeling heartened was also sad because that should be the norm, not the exception. Dr. David O’Shields shared information he received from the school librarians in his district! He collaborated with them to get facts! No one else on the state board has done this most basic of actions.

Now that one school year has passed for us to observe how the state board has implemented the regulation, we continue to encourage parents whose children are directly affected to be in touch with the state board members as well as their state representatives and senators. We also continue to point out how arbitrarily the regulation has been implemented, which opens the board up to legal action. SCASL repeatedly offers suggestions to amend the regulation which so far have not been taken up by the board. But we know the majority of people across the state do not agree with the regulation or how the board has implemented it. It’s a matter of impressing upon the board and Superintendent Weaver how unpopular it is, and getting members of the state legislature to understand how much of a legal problem this regulation is. It also seems to me that district superintendents and school board members could advocate against the regulation directly to Superintendent Weaver and the state board members because they do often work together. That level of support would go a long way to boost school librarians’ morale.

Ultimately, the state school board members are the ones who have the power to reverse the damage being caused by this regulation by amending or repealing it. We will continue to exercise our rights as citizens to dialogue with them, to present facts and testimony, and to encourage them to exercise their leadership responsibilities by eliminating such a harmful practice and get back to the real issues facing South Carolina’s students.

Something that should be emphasized here is that books which have been banned at the state level have been titles challenged by TWO adults in the entire state. That’s two adults who have been given so much power that their complaints–cherry picked passages from the banned texts–led to books being banned in every single school. When and how does the actual public push back against this? Do they even know? Where and how do you get parents and public school advocates to spread the message that some random person on the other side of the state has been given the power to determine what happens in *their* schools . . . especially as those parents were denied their requests to ban the books in their own local schools?

Jamie: One part of our advocacy and outreach work is to educate the general public about what has been happening this school year. We all know how difficult it is to keep up with current events and issues in society, and sometimes people want to be informed and even get involved but simply are overwhelmed and cannot keep up on their own. SCASL leadership sends out an email to members after each IMRC and full state board meeting, providing summaries, email addresses for officials, and suggested talking points. Many people have told us how helpful these emails are to keep them informed. Local and state news outlets have also been providing coverage for this issue, and several have given us the opportunity to represent school librarians and students, which we greatly appreciate.

It is certainly the case that many, many individuals and organizations have been speaking out across the state over the past year. People are certainly staying informed and are making their voices known to their elected officials. I suppose at some point it’s the age-old problem of elected officials actually listening to their constituents instead of simply following their own political ideology.

What is the impact of these bans on students? What are you hearing from them?

Tenley: At the end of the school year, I was shifting the collection to create more room for graphic novels and manga, and several students voiced concerns because they thought we were removing books. Students are aware of the regulation. High School teachers across the state have restricted access to or entirely removed their classroom libraries because of the requirement to catalog their books and follow the regulation guidelines.

Jamie: Although I work at an independent school and am therefore not affected by the state board’s actions, I know that my students are aware of what’s happening because they will ask me questions. It baffles them to think about why the state board thinks these books are “harmful” enough to ban given everything else they face in society today, especially in terms of technology. While they realize that their rights at my school are not at risk, they still are very much concerned about the wider implications.

Students pay attention, and they hear what is being said about them. Consider how damaging it is for a young person who identifies as part of the LGBTQ+ community to continually hear legislators and state board members talk about their community as if it is too inappropriate or dangerous to be represented in school libraries. Stakeholders need to stop sexualizing entire minority groups. All students have the right to attend school in a safe environment that provides equal and inclusive access to representation regardless of officials’ personal beliefs.

Where and how does the state–currently ranked 40th in education nationally–plan or consider addressing the inequities they’re putting onto their students? How can students in South Carolina be competitive academically to peers in other states when it comes to college admissions, to advanced placement tests, or similar when they’re denied access to books that those peers have? (I suspect you’ll cover it here, but $$$$, obv.)

Tenley: I am very concerned about the impact the regulation will have on students’ preparedness for higher education.

Jamie: Unfortunately, the book banners argue that they are not banning books, they are simply removing inappropriate materials. They also argue that students and parents can still check out these books from public libraries or buy them from Amazon or the bookstore, so therefore they aren’t banning books. Superintendent Ellen Weaver also decided in June 2024 to disallow any school districts to offer the AP African American Studies course because it’s too “controversial.” Weaver and her allies have created an atmosphere that is, I would say with confidence, hostile to higher education, which aligns with the efforts of other nationwide organizations and political movements. Thus, they are not concerned that their unconstitutional actions will harm students’ abilities to achieve academically; rather, they think they are providing sacred protections against evil which will illogically make them stronger students by eliminating “liberal indoctrination.”

To be more specific, Superintendent Ellen Weaver hired Dr. Mark Herring as the Education Associate for school libraries and librarians in the state department of education, and there has been rhetoric from the department criticizing USC’s iSchool program. I won’t provide a link to his “writings,” but he has written pieces claiming that the American Library Association is a far left-leaning radical institution, and even includes higher education institutions in this evaluation. It is troubling to read his attacks on higher education given his new position. He also has never worked as a school librarian (similarly, Ellen Weaver has never worked as an educator). So we do see the book banning as just one part of a strategy to devalue and create distrust in current higher education institutions in this state.

When, where, and how does this end? Is it when there’s a state-wide voucher program allowing taxpayer money to be used to send wealthy kids to private schools so they don’t need to be near books their parents deem “inappropriate?” Is it when there are no public schools? Is it when there are so many books banned that keeping a list of acceptable books is shorter and easier? In other words, what is even the path forward at this point?

Jamie: Once the regulation was passed last summer, we knew it would take time to reach a point when the tide would turn. We endured this first year of the regulation’s implementation and now have a better idea of how the board intends to utilize the regulation although it is still very much a guessing game as they pick and choose which types of sexual content are age inappropriate (from the board: “descriptions require enough ‘explanatory detail’ to form a mental image of the conduct occurring”). I’m not sure how Dr. Christian Hanley, chair of the IMRC, expects me to know what types of mental images he’s forming as he’s reading the excerpts provided by a complainant.

The South Carolina legislature is very much interested in bolstering a statewide voucher program, and recently passed new legislation with this very goal in mind (last year’s attempt was struck down by the state supreme court, but of course that didn’t stop the Republican-controlled legislature from simply trying again). Ironically, though, this push toward private schools means no government oversight or control; the school library in a private school is not controlled by Superintendent Ellen Weaver.

We need people who are normally swayed by the rhetoric surrounding vouchers to realize the reality of utilizing private schools on a mass scale. Private schools do not necessarily provide the resources needed for learning differences, students with severe disabilities, students who need assistance through free or reduced-cost meals, language support, transportation, and more. There aren’t enough private schools to replace the public school system. Teachers are generally paid less than through the state system and are not required to have professional certification or continuing education. Charter schools are not a panacea either; what happens when the authorizer’s structure fails, forcing them to close? It may only be when there aren’t enough public schools open, and a private school isn’t an option, that working parents finally understand they’re being lied to for someone else’s political gain.

In terms of book banning, it helps that one person can only submit 5 book challenges per month to the IMRC, and so far only two citizens have utilized the process. I’m confident that as advocacy efforts grow after this first year, and the board’s actions become ever more unpopular, there will be a point at which the board will have to reconsider the regulation’s purpose, which means reminding them of Ellen Weaver’s political agenda in creating it in the first place, which had nothing whatsoever to do with the over 750,000 public school students in South Carolina.

Also, Ellen Weaver is serving in an elected position. We look forward to meeting the people who will decide to run against her.

How do you keep yourself moving forward? How do you maintain hope?

Jamie: This is a tough one because book banners have engaged in such personal attacks. But as often happens in times of trials, our organization is stronger than ever. For the second year in a row, we have over 1,000 members which is an incredible and humbling show of support and faith in what we do. We celebrated our 50th anniversary this year and were so grateful to have the support of so many past SCASL leaders and supporters. Our collaborators and colleagues let us know how much they support us and believe in us in so many ways which keeps us motivated to continue to advocate for students. We also know that intellectual freedom is the basis of our profession and of American society, and we are honored to be involved in this work.

Many of us have endured personal attacks for the past three years, which has been a long time. Of course there are personal ups and downs, but in my really low moments, I try to remember all of the students I’ve had in my life who have shared how much I impacted their lives. I make sure I print out emails, save notes, take screenshots of lovely comments on social media, etc., and look through those during low moments. I also have notes, emails, messages, and memories from colleagues who have supported me from the very beginning. I wouldn’t know some of the truly exceptional people who are in my life now if it weren’t for the bad stuff. Ultimately, I actively make the decision not to allow the bad actors to control my life.

I also try to remove myself from the situation and remember that book censorship has been part of American society since the very beginning. As Ibram X. Kendi said at the 2023 ALA annual conference in Chicago, the freedom fight chooses you. I may never know why it chose me, because there have been some truly deeply hurtful times, but I’ve been entrusted with this responsibility on behalf of my students. I won’t solve it, but I’ll do my part. And when enough of us are doing that, we will achieve victories and inspire future generations to continue the work as well.

What can South Carolinians do to protect access to books and school libraries? What about Americans who live in other states? Where and how can they support efforts to protect the freedom to read in South Carolina, in their own state, and nationally?

Jamie: People who don’t work in libraries probably don’t realize how important it is to use the library! We rely on our checkout and usage statistics to make all sorts of decisions. If a book is labeled as “controversial,” read it yourself! Partner up with a school librarian who can explain what literary merit means and how we select books which fairly represent all types of people. Ask a school librarian to host an event at a public library to raise awareness of intellectual freedom rights in America. The public library is one of the original community meeting spaces!

We need everyone to speak up, especially on behalf of the school librarians who can’t be involved. Most people don’t realize that school librarians are the first and perhaps only line of defense in a school for students’ First Amendment rights. It’s a sacred, sacred profession and should be treated as such. Please contact your state representatives and senators, your representative on the state board of education, and your local school district board members. Make sure they know your name. Go to meetings regularly. Establish a presence so they know you are watching. And when I say “you,” I mean your network. Please join your state’s school library association and public library association. They will help you stay informed and let you know their goals and values in terms of talking points.

The tide is undoubtedly turning against Moms 4 Liberty and other radical, extremist groups in terms of elected positions. Consider running for a position to add a balanced, moderate, educated voice to your local and state-level school boards. People who are invested in and who care about their local community are the ones who should be in leadership roles, not those with national political ideologies.

What is happening is not inevitable. In true American tradition, those of us who deeply care about democracy and intellectual freedom will continue to show up until this iteration of Ellen Weaver’s fascistic leadership has faded into the background. And we will remain as organized as ever, ready to ensure the rights of the freedom to read for the next generation. We’d love to have you join us.

Book Censorship News: June 13, 2025

Psst: it’s time to start tracking attacks on Pride-related programs, book displays, and library collections. If you’ve experienced censorship or targeted attacks related to Pride leading up to June or anytime throughout June, please document that here. It’s anonymous and will be used to catalog the ongoing attempts at Pride-related censorship (see 2023 and 2024 roundups).

- Beginning with good news: St. Francis, Minnesota, schools settled lawsuits that they were involved in over their use of BookLooks to censor library collections. Recall that Minnesota is an anti-book ban state, so the settlements involve, well, following state law. The laws are only as good as their enforcement.

- A two-year fight over access to LGBTQ+ books means that Yancey County Library in North Carolina is pulling itself from a regional system that provides even more access to more books to its patrons. Cool, cool.

- I’ve got a feeling any of the book ban court cases hinging on the First Amendment happening in the south aren’t going to be going well after the Fifth Circuit decision. But the fight continues as parents who sued in Florida over book bans are appealing a judge’s dismissal of their case.

- “No data on how often ‘sexually explicit’ books accessed by Alberta [Canada] students: minister.” That’s because the answer is that there are not ‘sexually explicit’ books in schools.

- How the Christian far right took over Cy-Fair Independent School District (TX), the state’s third largest district.

- A Colorado resident is spearheading a national group to help those in the military service fight for their right to read.

- “This crusade was never about protecting students. It was about theatrics, fearmongering, and imposing personal beliefs on a public institution. The result: wasted time, taxpayer dollars, and damage to Pine-Richland’s reputation.” This opinion piece raises a great question about the restrictive book ban policy shoved through a Pennsylvania school district–why didn’t the eager book banners ban the book they were insisting they’d attack immediately?

- Former Librarian of Congress speaks out after being fired by Trump.

- West Michigan librarian Christine Beachler talks about the lawsuit she filed against the Moms For Liberty member who has spent years harassing her for simply doing her job.

- Madison-Grant United School Corporation (IN) has banned We Are The Ants from the district. The reasoning is super great: ““It was checked out by an eighth-grade student, who took the book home. [The] mom took a peek at it and said it was not appropriate.” Cool–one parent “took a peek” and the school removed its access from all.

- A real Alabama gem of a human who has harassed trans librarians and called for bans on books that aren’t even in the library she’s complaining about is now running for Madison, Alabama’s city council.

- Due to IMLS cuts and state funding shortfalls, the Washington State Library is eliminating 12 jobs and shutting down to the public, among other devastating changes.

- Author Cat Winters talks about the push to pass an anti-book ban bill in Oregon.

- Speaking of, the anti-book ban bill in Oregon passed in state congress and is now on the governor’s desk.

- Connecticut passed their anti-book ban law in the legislature, too, and now it hits the governor’s desk.

- The group Action4Canada is taking credit for the province of Alberta moving to ban books in schools. Here’s their current list of “naughty” books with decontextualized, cherrypicked examples.

- Guess what? In shocking (/s) news, residents of Huntington Beach, California, don’t want their library sold to a private organization and don’t want books banned or restricted–a reminder that MAGA brained city leaders were only ever caring about their MAGA ideas, not the needs of their community.

- In the ongoing fight over book and curriculum censorship in Redlands, California, this story about a public prayer focused on inclusivity is a real refresher.

- The ACLU of Mississippi is among those who have sued the Mississippi education boards over their slate of anti-DEI legislature passed this session.

- A really important piece written from a person experiencing incarceration in Georgia about how hard it is to get into the prison library.

- This week saw the first library bomb threat in several months. Provo Library (UT) was the recipient.

- A private Christian university in Idaho removed their Pride book display following online complaints by a local legislator. Recall: it’s a private university teaching almost all adults.

- Garfield County Public Library District (CO) board members have been fighting about relocating manga for a long time in the public libraries there. They won’t be doing that. They will, however, consider one of those minor-access cards which restricts what young people can borrow.

- Brookings School Board (SD) revised their book challenge policies and now it will require more work before a book is removed from access by all; parents can much more easily restrict books for just their kid. This . . . is common sense. Among their requirements during a formal challenge? Reading the whole book.

- “Arizona Superintendent Tom Horne is calling the Scottsdale Unified School Board “woke” for a book he claims is anti-police but the district says he’s out of line, accusing him of inflammatory rhetoric. Horne says the textbook goes against DEI guidelines and plans to report the district to the feds. Scottsdale Superintendent Scott Menzel said critics of the book haven’t read it.” Sigh.

The following comes to you from the Editorial Desk.

It’s Pride Month, and while we celebrate queer literature here all year long, we go especially rainbow bold in June. This week, we’re excited to take a look at the favorite queer books of beloved queer authors.

Read on for an excerpt and become an All Access member to unlock the full post.

It’s Pride month, which is the perfect excuse to buy and read a bunch of queer books. One method I really enjoy for finding new books is to take the recommendations of my favorite authors. Carmen Maria Machado hasn’t led me astray yet. Unfortunately, I don’t have these authors on speed dial, but luckily, they usually have shared their recommendations publicly.

Below I’ve put together queer book recommendations from 11 beloved queer authors. Some are from interviews where they discussed their favorite books, and others are book blurbs. Both the authors’ works and the books they recommend cover a wide spectrum of genres and formats, including graphic novels, literary fiction, poetry, biographies, horror, sci-fi, YA fantasy, and more, so there’s something for every kind of reader.

Akwaeke Emezi recommends…

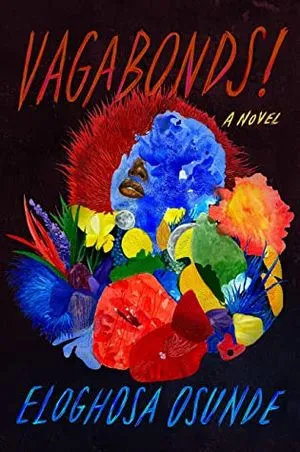

Vagabonds! by Eloghosa Osunde

“Some of the most spectacular writing I’ve ever encountered in my life… Vagabonds! brought me to tears because it gave me a world in which my country could be home again.”

Sign up to become an All Access member for only $6/month and then click here to read the full, unlocked article. Level up your reading life with All Access membership and explore a full library of exclusive bonus content, including must-reads, deep dives, and reading challenge recommendations.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·