During the shooting of Lindsay Anderson’s 1987 film The Whales of August, the notoriously difficult Bette Davis vented an irrational animus toward her mild-mannered costar, the ninety-four-year-old Lillian Gish. When the director commented that Gish had just given him a perfect close-up, Davis retorted, “She ought to know about close-ups. Jesus, she was around when they invented them.” That catty gibe about the former silent-film ingenue—who was fifteen years Davis’s senior—alluded to D. W. Griffith’s innovation, seventy-five years earlier, of tight camera focus to highlight Gish’s delicately expressive face. The still close-up was, however, actually devised a half-century before Griffith, by the pathbreaking British photographer Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879), just one of several audacious advances we can credit to this formidable figure.

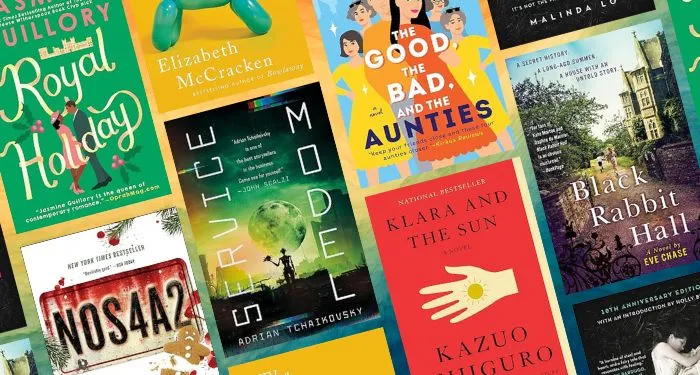

She is now the subject of an illuminating survey, “Arresting Beauty: Julia Margaret Cameron,” at New York’s Morgan Library and Museum, the final stop on a two-year international tour that originated at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, which began acquiring Cameron’s work during her lifetime and now has the largest collection of it anywhere, including the more than one hundred photographs displayed here, about one tenth of the V&A’s cache. The exhibition allows us to see why this genteel rebel’s personal approach to the young medium did not sit well with her less imaginative rivals. She had ample reason to seek new directions. Within just three decades of photography’s emergence in the 1830s, its practitioners had already settled into a host of stultifying conventions, including showing sitters almost always at full height or at least bust length, using a high-focus lens setting to emphasize minute details of attire that indicated superior social status, and favoring precision and clarity over mood and atmosphere.

Cameron rejected those strictures. Convinced that a photograph could be the artistic equal of a painting, she employed techniques that expanded the camera’s expressive potential. For instance, one day, as she adjusted her lens before making an exposure, she realized her preference for soft-focus resolution. Cameron’s somewhat hazy compositions—analogous to the smoky sfumato shading achieved by Leonardo and other Italian Renaissance masters—incurred the derision of contemporaries who regarded razor-sharp outlines as a sign of high professionalism.

Sitters for early daguerreotypes struggled to remain perfectly still for minutes on end. Cameron, like her peers, used newer glass plates that were much more light sensitive. But where her competitors tried everything to shorten exposure time, which they reduced to as little as twenty seconds by the 1860s, she did the opposite: the extended length of Cameron’s exposures, throughout which her subjects could not constantly hold their breath, gives her images a lifelike presence. That effect is exemplified by She Walks in Beauty, a mesmerizing 1874 figure study of the actress Isabel Bateman, swathed in drapery like a Classical sculpture and emitting a tremulous radiance that borders on the supernatural.

Cameron was likewise unfazed by mishaps that occurred during the wet-plate collodion process, a tricky method in which the viscous developer could puddle on the flat glass photographic plate (called “oystering”) and show up in the finished image. Similarly, if a plate cracked but she was fond of the composition, she printed it anyway. Rather than rejecting such imperfections as disqualifying flaws, Cameron considered them sympathetic contributions of fate.

Some not only saw her as a sloppy technician but ascribed that perceived laxity to her gender. In 1873 one critic wrote of her photographs, “There must be some excuse made for their being the work of a woman; but even this does not necessitate such fearlessly bad manipulation.” With commendable sangfroid she brushed off such sexist attacks, deeming their “irony and spleen” simply “too manifestly unjust for me to attend to.” Her detractors could not comprehend her sense that the medium was a physical extension of the photographer rather than merely the outcome of a chemical reaction. As a result, her pictures are infused with a palpable humanity lacking in the period’s routine photography, as she was well aware.

The most entrepreneurial British camera portraitist of the day was John Mayall, whose inexpensive, mass-produced carte de visite albumen prints of Queen Victoria, the first broadly disseminated photographs of a British monarch, were wildly popular even though his likenesses were stiff and inert. Cameron sardonically wrote that the contrast between her and Mayall’s respective images of Alfred Tennyson, Britain’s poet laureate and a good friend to whom she moved next door on the Isle of Wight, “seems too comical. It is rather like comparing one of Madame Tussaud’s waxwork heads to one of [the Pre-Raphaelite sculptor Thomas] Woolner’s ideal heroic busts.”

Unlike Mayall, Cameron never accepted portrait commissions. She decided whom she would photograph, but hewed to traditional typecasting based on men’s professional accomplishment and women’s physical attractiveness. Her impressive roster of lionized male subjects included Charles Darwin, Thomas Carlyle, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Two repeat sitters were her mentors of long standing: the polymathic astronomer John Herschel, who also invented the cyanotype photograph, and her principal artistic counselor, the celebrated painter George Frederic Watts, whose sage advice and unstinting support, she wrote, “gave me such encouragement that I felt as if I had wings to fly with.”

The most telling sign of Cameron’s artistic aspiration is her close study and conscious evocation of the old masters, evident in so many of the pictures she took and the titles she gave them. She became familiar with classics of European painting from the Renaissance onward through the high-quality reproductions issued by an art appreciation society she belonged to, a precursor of the illustrated publications that would become an agent of cultural literacy in the twentieth century. The 1864 photograph she called A Sibyl after the manner of Michelangelo was closely modeled after the Erythraean Sibyl, one of the ancient seers he depicted in his Sistine Chapel frescoes. Although the dark tonality Cameron achieves here is at odds with the high-keyed Mannerist colors of the original (which in any case remained muted until the restoration completed in 1994), she knew it only through monochrome prints that worked to her advantage in conveying the terribilità of Michelangelo’s masterwork.

*

Accompanying the exhibition is a catalog written by Lisa Springer and Marta Weiss, the Victoria and Albert photography curators who organized the show. This well-illustrated volume is a useful introduction to Cameron, but two other recent books offer more substantial analyses. Nichole Fazio’s Julia Margaret Cameron: A Poetry of Photography presents a probing account of her artistic practice, whereas Jeff Rosen’s Julia Margaret Cameron: The Colonial Shadows of Victorian Photography focuses on her place within the British imperialist adventure at its zenith.

Cameron’s work reflected her family’s deep involvement in the colonial enterprise, which she addressed much more directly than, say, Jane Austen, now often faulted for her glancing references to the triangular colonial slave trade that financed the upper-class society she satirized in her novels. Julia Margaret Pattle was born in what was then Calcutta to a British expatriate family; her father worked for the all-powerful East India Company. Her much older husband, the British jurist Charles Hay Cameron, had helped write the penal code for the Indian Raj before buying a coffee plantation in Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka).

Remarkably, Cameron took up photography at the advanced age of forty-eight, at a time when the average lifespan of British women was five years less than that. In 1863 her daughter and son-in-law gave her a camera to occupy her during her husband’s long absences overseeing their colonial estate. She took to the new technology with amazing speed, and after just a year assembled thirty-nine images that she rated good enough to give to Watts in a presentation album (now held by the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York).

In 1875 the couple, who had six children (Julia herself was one of seven sisters), retired to Ceylon from their home on the Isle of Wight, which they’d named Dimbola after their estate on the tropical island. There Cameron made photographs of local people in two distinct modes: ethnographic portraits distinguished by their documentary candor, such as Two Young Women (1875–1879), and poetic groupings that transposed her fanciful narrative style into tropical settings, including A Group of Kalutara Peasants (1878), as carefully posed as a choir of Pre-Raphaelite angels.

Among the most startling photographs on view at the Morgan are two that depict the Ethiopian prince Alemayehu. In 1868 he was orphaned at age seven during a British military action when his father, the emperor Tewodros II, killed himself to prevent being taken by the invaders. (A Cameron portrait of the ruler’s would-be captor, Lieutenant General Robert Napier, is also included in the show.) Because of Alemayehu’s royal status, he was brought to England at Queen Victoria’s behest and was initially installed on the Isle of Wight, where she summered at her seaside villa, Osborne House. Half charity foundling and half exotic trophy, the exiled boy was photographed by Cameron along with an Ethiopian attendant and his army guardian—who had the Dickensian name Captain Tristram Speedy—in a one-shot summary of the grotesqueries possible when the sun never set on the British Empire. The unlucky prince, who was sent to the Rugby School and then the Sandhurst military academy, died of pleurisy at eighteen. He was buried in the crypt of St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle, the final resting place of British kings and queens, most recently Elizabeth II.

Although Cameron’s most talented female contemporaries—Anna Atkins and Clementina Hawarden—lapsed into posthumous eclipse, her renown never faded. That was owed to her being arguably the first photographer to create an instantly recognizable and wholly consistent personal style. One can identify an archetypal Cameron photo from ten feet away, thanks to its rich sepia background, strongly defined silhouettes, sensuous treatment of voluminous hair, and aqueous lighting effects that impart a shimmering aura. No artist’s signature is needed, although sign she did.

Her enduring esteem also had much to do with her definitive portraits of eminent Victorians, which continued to be widely reproduced long after her death in Ceylon at sixty-three. The best are assembled in a maroon-walled inner sanctum at the Morgan under the rubric “Famous Men.” Among them is a photograph signed by Darwin, who, like Herschel and Tennyson, helpfully complied with her requests for autographed prints she could sell at higher prices.

From the outset Cameron’s bifurcated output drew mixed reactions. She won unanimous praise for her portraits, but there was less enthusiasm for her staged Biblical, mythological, and literary tableaux. The critical split was summed up by Bernard Shaw, who reviewed a Cameron memorial retrospective ten years after her death. Although he averred that her headshots of Carlyle, Herschel, and Tennyson “beat hollow anything I have ever seen,” he dismissed her “photographs of children…inartistically grouped and artlessly labeled as angels, saints, or fairies.” A deeply devout Anglican, Cameron possessed a sincere religiosity that could veer toward the saccharine. It has never been for everyone. Following the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, mid-Victorian Protestants remained wary of resurgent “Popery” as the Oxford Movement’s Anglo-Catholic ritualism gained adherents within the Church of England.

I experienced a version of this dichotomy in my own household early in the millennium, when a hand-signed print of Cameron’s La Madonna Riposata/Resting in Hope (an image not in this exhibition) hung among our other nineteenth-century British art after I snapped it up at a bargain price. This 1864 photograph depicts a pensive young woman (the family’s housemaid, Mary Hillier, Cameron’s go-to model for the Virgin Mary) holding an infant asleep in her arms, one of the photographer’s many variations on this recurrent theme. After a while my wife, the art historian Rosemarie Haag Bletter—who grew up in a German Protestant family that scorned such Katholisch iconography—confessed that she really didn’t want a Madonna with baby Jesus on our walls, no matter who the artist was. So off it went to the Brooklyn Museum, where mother and child, so tender and mild, now reside.

*

Rosemarie would have absolutely no trouble living with The Mountain Nymph Sweet Liberty. It caused her to pause as we walked through the Cameron show at the Morgan, which was arranged by its photography curator, Joel Smith, and his new assistant curator, Allison Pappas. This arresting portrait of a young woman known to history only as Mrs. Keene, directing her intense gaze straight toward the viewer, prompted an admiring response from my wife much like that of Herschel, who 150 years ago found this photograph “a most astonishing piece…absolutely alive and thrusting her head from the paper into the air.”

With today’s increased emphasis on personal identity, opinion about Cameron’s costumed set-ups has become notably more favorable. In her own day, when fancy dress balls were all the rage, the upper classes could disport themselves as figures from an imagined historic past, while the less affluent could improvise with homemade theatricals drawn from scripture and legend. What both had in common was a comforting respite from a sometimes menacing present as the onrush of modern life altered age-old certitudes. If photographs such as her extensive suite of illustrations for Tennyson’s poem Idylls of the King appear as though they were contrived from a dress-up trunk, they also foreshadow Cindy Sherman’s inspired cosplay as heroines in old master paintings. On occasion, though, the getups chosen by Cameron can look arbitrary to the point of comedy. Her white-bearded friend Henry Taylor, the poet and literary critic, wore the same crown and embroidered Indian robe to impersonate two different Old Testament kings—the Persian Ahasuerus and the Israelite David—but those photos have been sensibly separated in the Morgan installation to minimize their redundancy.

One cross-generational affinity I hadn’t thought of before is advanced by yet another recent book, Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In by Magdalene Keaney, which accompanied an exhibition held at London’s National Portrait Gallery in 2024 that paired work by the two women. The enormously gifted, terribly troubled Woodman suffered from depression and committed suicide in New York in 1981 when she was twenty-two. During her truncated career, she imbued haunting black-and-white images with a tangible sense of vulnerability markedly different from the strong resolve evident in Cameron’s photographs.

At first I was skeptical—Woodman’s untitled 1976 lineup of three masked female nudes reminds me more of Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon than of Cameron’s The Three Marys. But prolonged viewing persuaded me that the two photographers are indeed united, as Keaney writes, by their shared “approaches to staging photographs, the use of props and costume, how the figure relates to space and architecture, the use of expressive, emblematic gesture and the manipulation of focus.”

Although not all of these juxtapositions are convincing, several of Woodman’s images uncannily (and apparently unintentionally) parallel Cameron’s, such as a 1980 series of female figures, in pleated Classical garb and with arms uplifted, who evoke caryatid columns on ancient temples. Very much in that spirit is Cameron’s 1867 composition After the Manner of the Elgin Marbles, inspired by the famous Parthenon sculptures now held by the British Museum and subject to an ongoing repatriation campaign waged by Greece. In the photograph, two young women dressed in white Grecian gowns are seated at right angles to each other—one facing us, the other in full profile. Their divergent gazes speak to both engagement and contemplation, the dual qualities that Julia Margaret Cameron brought to an epochal body of work that still communicates to viewers a century and a half after it was made.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·