In conversation with a fellow reader recently, I asked if she had read the novel Stoner by John Williams. “Oh yes,” she replied. “I’m in the cult.” Oh! While I don’t think all the fans of this book are busy with secret rituals, there are I suspect, fewer of them than there should be. The same is true to a greater or lesser extent for all the books on this list. Although they’ve been celebrated in some corners of the literary world, they deserve a bigger audience.

Stoner by John Williams

I came to this book only in the past couple of years when a friend recommended it to me. I should have already known it, not just because it is so very good, but because it is set at the University of Missouri in Columbia, MO, the main campus of my alma mater, where John Stoner spends much of his working life. Stoner was raised on a failing farm, the only child of stoic, taciturn parents who expected him to return to the farm and save it by means of the knowledge he’d acquire studying agriculture at college.

Once at school, however, Stoner falls in love with a world of literature and intellectual enrichment, which makes returning to the farm an impossible-to-imagine prison. “The love of literature, of language, of the mystery of the mind and heart showing themselves in the minute, strange, and unexpected combinations of letters and words, in the blackest and coldest print—the love which he had hidden as if it were illicit and dangerous, he began to display, tentatively at first, and then boldly, and then proudly.” He’s found his calling and there is no going back. He marries a woman he loves passionately, but only briefly, as they evolve into different people who don’t, in fact, know each other at all. Once again, the love of his life lies elsewhere.

The first time I read the book it struck me as being about a sad life, constricted by unavoidable circumstances. Upon rereading it, however, I think the book is about the beauty and satisfaction of a life in which happiness, success, achievement, and love are present intermittently, sometimes in half-measure. The writing, direct and straightforward on the surface, is brilliant in its ability to capture layers of meaning in both plot and character.

The Heart is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers

The title of this book is so familiar that almost everyone thinks they’ve read the book. I thought so too, but when pressed to describe the book, most people, myself included, only remember key words: The South, prejudice, loneliness. I read (or maybe re-read) it recently and was astonished by the talent of McCullers as a 22-year-old. Her empathetic portrayal of the many wounded souls, odd ducks, and disappointed dreamers of this unnamed small town in Georgia is something few mature writers could achieve. I suspect the book may have fallen out of favor because it doesn’t flinch from the derogatory terms and bigoted notions of the late-1930s era in which it is set. Those terms do grate and shock, but I have no doubt the author used them for that very reason. She adds them to the other tools she employs to illustrate all the ways humans create artificial barriers against connecting with each other.

Racism, antisemitism, sexism — most of the -isms are on display in the book—all of them contributing factors to the pain of loneliness. McCullers understands the relentless ache of aloneness and describes its pain succinctly: “The way I need you is a loneliness I cannot bear.” Another character speaks for all of us when he recites one the best known lines from the book: “I’m a stranger in a strange land.” This book made me cry many times, but I also laughed, and could not help but love its cast of lonely beings.

The Great Fire by Shirley Hazzard

Say the name Shirley Hazzard and most readers immediately think of The Transit of Venus, a masterpiece that deserves to be praised. Oddly, however, her other National Book Award-winning novel, The Great Fire, seems to be less widely known. Perhaps I am wrong and they are equally beloved, but the results of my one-woman, unscientific survey show it to be the little sister of the two.

We can’t, however, begin a consideration of either book without commenting on the incredible talent that was Shirley Hazzard. Her sentences are one clever assemblage of words after another. A couple of examples: “[She had] a piping voice, alive with falsity.” and “When you realize someone is trying to hurt you, it hurts less. Unless you love them.” The title is a general reference to all the fires of WWII, a specific reference to the atomic incineration of Hiroshima, and maybe also a reference to a smoldering love affair. Two veterans of the war meet again in Asia and grapple with the lingering effects of their time as soldiers, and the devastation the war they won left behind in the countries of their enemies. (Hazzard’s descriptions of Hiroshima are by themselves a kind of unforgettable devastation.)

The love affair involves Aldred Leith, one of the veterans, and Helen Driscoll, an Australian teenager at the time of their meeting, who is older than her years due to family and wartime trauma. Hazzard handles the attraction between them perfectly, balancing concerns about its inappropriateness with the acknowledgment that it might be a love that redeems them both. The closing lines (they are intentionally ambiguous—not a spoiler from me): “Many had died. But not he, not she; not yet.”

Gilead by Marilynne Robinson

How can a book that won the Pulitzer Prize be on this list? Gilead received rave reviews when it was published in 2004, but seems to be relatively little known now, for reasons I can only guess. Too religious? Too “quiet”? Too cerebral? Whatever the reason, it deserves all the praise it received back in the day and much more than it is receiving now, 20 years on. John Ames, the protagonist, is a 78-year-old Congregational minister dying of heart disease, and the father of a young son who, he is well aware, will grow up without a father.

Rev. Ames writes his son letters so the child will know about his father’s life, which stretches back to the early years after the Civil War, and so his son also will know the family history of ancestors who were abolitionists, theologians, virtuous men who nevertheless committed their share of sins. The letters are further the only way Ames can share with his son his innermost thoughts and the values he hopes might shape the boy’s character. Most importantly, Ames is writing to let his son know how much the child was loved, “to tell you that if you ever wonder what you’ve done in your life, and everyone does wonder sooner or later, you have been God’s grace to me, a miracle, something more than a miracle.”

When John isn’t writing those letters he’s engaged in philosophical discussions with his good friend and fellow pastor, Boughton, or trying to understand the mysterious woman he loves, Lila, his outsider second wife. Of her, Ames writes to his son, “She has watched every moment of your life, almost, and she loves you as God does, to the marrow of your bones.” The notions of grace, compassion, and forgiveness are woven with skill throughout every page of the story.

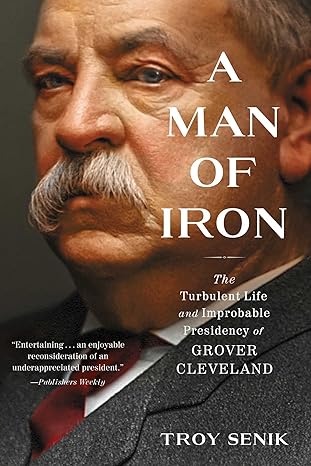

A Man of Iron: The Turbulent Life and Improbable Presidency of Grover Cleveland by Troy Senik

A Man of Iron: The Turbulent Life and Improbable Presidency of Grover Cleveland by Troy Senik is an under-praised biography of a relatively unknown President. First elected to the Presidency in 1884, Cleveland rose up the ranks of the New York State Democratic party to the apex of American political power by being pro-fiscal conservatism, pro-government reform, pro-stubborn as a mule.

He campaigned so vociferously against the era’s dominant, corrupt patronage and bossism system that even Republicans came to support him. He was a firm believer in limited executive power and (mostly) stuck to his guns even when others begged him to assume more power to himself. Because of his refusal to step in and “solve” the economic disasters that overtook the country during his second term, his popularity plummeted and he did not run for a third one (permissible before the passage of the 22nd Amendment in 1951).

The book is a well-researched character study of our 22nd /24th President, whose political philosophy is perhaps best summarized in this quote: “You will find plenty of [men] who will smile at your profession of faith and tell you that truth and virtue and honesty and goodness were well enough in the old days when Washington lived, but are not suited to the present size and development of our country and the progress we have made in the art of political management. Be steadfast … You will be told that the people no longer have any desire for the things you profess. Be not deceived. The people are not dead but sleeping. They will awaken in good time and scourge the moneychangers from their sacred temple.”

In addition to being a comprehensive, readable biography, the book is also a valuable primer on our balance-of-power system of representative government. Cleveland lived a vigorous life of public service, even out of office, with his impressive wife Frances at his right hand. His story should be a better-known part of our national lore.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·