Kelly is a former librarian and a long-time blogger at STACKED. She's the editor/author of (DON'T) CALL ME CRAZY: 33 VOICES START THE CONVERSATION ABOUT MENTAL HEALTH and the editor/author of HERE WE ARE: FEMINISM FOR THE REAL WORLD. Her next book, BODY TALK, will publish in Fall 2020. Follow her on Instagram @heykellyjensen.

It’s Banned Books Week in America. The annual event aims to highlight the realities of book censorship across the country while also encouraging book lovers to advocate for intellectual freedom. In recent years, the week has taken on even more weight as the number of book bans in public libraries and schools skyrockets; in recent years, it’s also felt more like marketing than a call for real, systemic change that supports our poorly funded, overly band-aided institutions of democracy. Despite this, it feels necessary to acknowledge what this week is about and where and how what’s championed one week per year should be applied every day of the year.

Books by and about people of color; books by and about queer folks; and books about gender, sexuality, and puberty have been the top targets of censors since this unmitigated wave of book bans began in 2021. Anything under the umbrella of diversity, equity, and inclusion (“DEI”) is being pulled or labeled, removed or othered. We’ve highlighted this multiple times per week since the far-right accelerated its bigotry at the local school and library level in Literary Activism. Because there’s a dedicated space to cover book censorship, it’s not been covered here as much as it could be. YA books are among the biggest targets because it’s a category that has heard demands for better representation in its stories and authors. Though there is plenty of work to do, YA has responded to those demands and over the last decade, diversified in meaningful ways.

There have always been YA books that tackle the topic of book bans, too. Among the early titles are Nat Hentoff’s The Day They Came to Arrest the Books, published in 1982 and Nancy Garden’s The Year They Banned the Books, published in 1999. We’ve seen the topic covered in books published in the last decade as well, including Banned Book Club by Kim Hyun Sook and Ryan Estrada, which dives into how authoritarian leadership in South Korea made books among their targets in amplifying their own power.

We’re now seeing these types of books, both fiction and non, grow in their numbers in YA. It’s not because book banning is trendy. It’s not because book banning sells books. It’s not because it’s a topic that writers think is fun to explore. And to be clear, those were never the thrust behind such books before, either. But today’s rising tide of YA titles exploring book bans are doing so because book bans are touching every single reader, writer, and advocate of young adult literature. To not see books touch on book censorship would be to overlook one of the biggest challenges facing this entire category of books and an entire generation of young people.

Samira Ahmed made waves with This Book Won’t Burn last year. This year, several more titles bringing to light the realities of today’s book bans are sitting alongside Ahmed’s. They include the nonfiction anthology Banned Together: Our Fight for Readers’ Rights edited by Ashley Hope Perez and featuring an array of voices, all of whom have seen their work banned (self included). Our this month is another work of nonfiction, Ban This!: How One School Fought Two Book Bans and Won (and How You Can Too) by a group of educators and students who successfully staved off two rounds of book bans at Central York High School.

Literary Activism

News you can use plus tips and tools for the fight against censorship and other bookish activism!

There are also several novels. Among them are Jasminne Mendez’s The Story of My Anger, as well as Frederick Joseph’s This Thing of Ours. Joseph and I dig deep into this book and the themes of censorship and student activism on the Hey YA podcast.

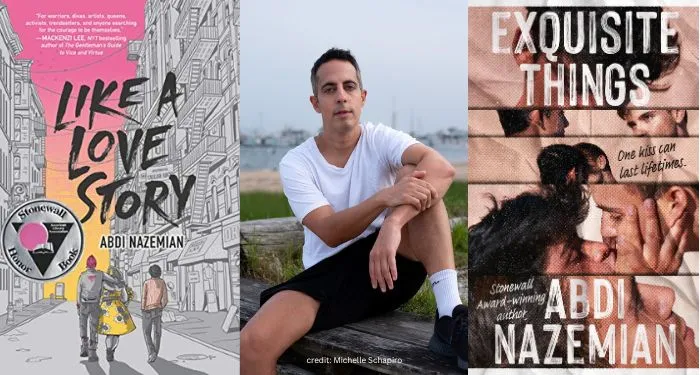

One more book exploring literary censorship in its contemporary manifestation hit shelves last month, too. Abdi Nazemian’s Exquisite Things was written in part as a response to his experiences seeing his prior work censored and as a response to the ways in which queer history is silenced and erased during periods of political extremism.

Today, Abdi shares his experiences under the thumb of book censors, as well as how he channeled his thoughts and feelings about it into his latest work of young adult fiction.

**

In my widely banned novel Like a Love Story, I write, “Tell your story. Because if you don’t, it could be wiped out.” And also, “What we did. What we fought for. Our history. Who we are. They won’t teach it in schools. They don’t want us to have a history.”

It’s a strange experience to write your queer immigrant coming-of-age story, to fill it passages about how the government of your adolescence didn’t want your stories told, and then to have the book banned. Like a Love Story tells the story of three high school seniors experiencing love, loss, and joy during the worst years of the AIDS crisis in New York City. It’s a novel about a time when there were no queer books in classrooms, when it took the President of the United States four years to merely speak the name of the virus that was devastating a community.

When the book was published, I felt a surge of happiness because I now lived in a time and place where queer Iranian stories like mine were given a platform. When the book began being taught in high schools, I was shocked and overjoyed. After all, this is a book where a character explicitly states that queer history will never be taught. Talking to students studying queer history through my novel was and continues to be one of the most moving honors of my life. But those classroom visits have greatly decreased.

That’s because the book is now banned statewide in Utah public schools, as well as in districts across Florida, Texas, and Virginia. Nationwide, this culture of fear has led to a decrease in queer books being stocked and in marginalized authors being invited to schools. I know fear well. I grew up with it by my side. Today, I feel personal heartbreak that young people are facing the same fear and shame I did when I was young. Once again, young queers are being told to remain invisible.

Which is exactly when we all need to get louder and prouder than ever. Book bans are never an isolated incident. Consider that LGBTQ content is being scrubbed from federal health websites, the NIH’s HIV Language Guide has disappeared, the State Department website has changed LGBTQI+ to LGB. This is all a coordinated effort we’ve encountered before and it’s clear a book like mine is being banned for fear that teens who read it will ask questions about similar moments in queer history and will learn to fight back from the ACT UP activists the book honors.

But we must also remember that fighting back doesn’t mean betraying our values. When the bans began to impact me personally, I responded to online attacks in a futile attempt to defend myself and I felt myself revert back to the scared, angry teen I once was. In time, I realized that the new challenge in front of me is holding onto my own values of empathy and forgiveness for all, and dealing with struggle in the best way I know how: by alchemizing it into art.

Which is why I’ve chosen to weave a response to book banning into my next novel Exquisite Things, the story of two eternal seventeen-year olds searching for a time and place where their love isn’t a crime. Exquisite Things’ protagonists are made immortal through the burning of Oscar Wilde’s original manuscript for The Picture of Dorian Gray. This is a commentary on how any attempt to destroy our stories will only make us stronger in the end. The Picture of Dorian Gray was once censored and banned. Now it is canon. Today’s long list of banned books might not all become canon, but I know that the message at their core will outlast any effort to make them invisible. Love and community will always outlast hate and division.

In Exquisite Things, I write, “We must love the life we’re given. It’s our most important job. And when our time is up, we must hand the world over to a new generation. We must give them our passions, our lessons, our art, our loves, our losses. We must give them our souls and hope they can find the same happiness we once did. Hope they’re as lucky as we once were.” This is the guiding principle of my novels: that in sharing histories that challenge dominant narratives, I might help readers love the life they’re given and keep passing that love on through art, communication, and human relationships grounded in empathy rather than fear.

Abdi Nazemian is the author of Only This Beautiful Moment—winner of the Stonewall Award and the Lambda Literary Award—and Like a Love Story, a Stonewall Honor Book and one of Time’s 100 Best YA Books of All Time. He is also the author of the young adult novels Exquisite Things, Desert Echoes, The Chandler Legacies, and The Authentics. His novel The Walk-In Closet won the Lambda Literary Award for LGBT Debut Fiction. His screenwriting credits include the films The Artist’s Wife, The Quiet, and numerous television series. He has been a producer, executive producer or associate producer on numerous films, including Call Me by Your Name, Little Woods, and Scotty and the Secret History of Hollywood. He lives in Los Angeles with his husband, their two children, and their dog, Disco.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·