This isn’t really my language, but the language I learned. So I’m reluctant to give something a name that is imposed on me.

—Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Nearly thirty years after Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s death at the age of thirty-eight, his artworks are instantly recognizable. His stacks of paper, his piles of hard candy, and his strings of lightbulbs all play with geometric form, serial repetition, and outsourced fabrication in ways that helped to redefine minimalism. Gonzalez-Torres altered its impersonal language by infusing it with emotion, reducing the scale of art objects, introducing mutability into his works, and in some cases—as with those stacks of paper—even inviting the viewer to take them. His candies can be eaten; his puzzles, photos, and photostats (made using an early-twentieth-century mechanical process in which images are reproduced on sensitized paper) are modest in size. He replaced the usual hard-edged materials—fiberglass, metal, and concrete—with paper, sugar, housewares, and memorabilia. Gonzalez-Torres also veered away from minimalism’s omission of references to things and ideas beyond the works themselves in his use of unlikely objects to represent people, such as sweets to represent his lover and his father. In doing so, he made us reconsider what we understand portraiture to be.

Josh T. Franco and Charlotte Ickes, the curators of “Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return” at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery and Archives of American Art in Washington, D.C., highlight the unusualness of Gonzalez-Torres’s approach to portraiture by juxtaposing his work with paintings and photographs from the museums’ permanent collections. They use the show to portray the artist both as a critic of American institutions and as an American Latino. Four black-and-white photographs from his series called “Untitled” (Natural History) (1990)—depicting four admiring descriptions of Theodore Roosevelt (“statesman,” “historian,” “scientist,” “ranchman”) carved into the façade of New York City’s American Museum of Natural History behind the plaza where the statue of him on horseback once stood—are hung alongside Adrian Lamb’s 1967 painting of the twenty-sixth president. Next to Gonzalez-Torres’s “Untitled” (Leaves of Grass) (1993), an installation featuring a string of lightbulbs, hangs Thomas Eakins’s 1891 platinum print of Walt Whitman. In the same room Gonzalez-Torres’s two photographs of colorful flowers—“Untitled” (Alice B. Toklas’ and Gertrude Stein’s Grave, Paris) (1992) and “Untitled” (Alice B. Toklas and Gertude Stein) (1992–1993)—are hung alongside Man Ray’s 1922 photograph of Stein and Toklas in their Paris parlor.

And Gonzalez-Torres’s stack of offset prints featuring 460 headshots of Americans killed by gunfire in one week—“Untitled” (Death by Gun) (1990)—sits in the first-floor corridor of the National Portrait Gallery, below Christian Schussele’s 1862 group portrait of American scientists and inventors. Among them is Samuel Colt, who designed the first mass-produced revolver. Also adjacent to the stack is a lithograph from the 1850s by John McGahey showing George Catlin firing his Colt gun in front of Carib Indians. These curatorial comparisons feel somewhat simplistic, restricting Gonzalez-Torres’s elusive and intentionally open-ended practice to a pedagogical exercise.

Between 1989 and 1994 Gonzalez-Torres created several text-based “dateline portraits” of individuals and museums, consisting of a few names or words referring to personal and public histories interspersed with dates, which challenged the conventions of portraiture by describing his subjects without rendering them figuratively. In a letter he wrote in 1994 to the subject of one of these portraits, he outlined his “subjective idea of what a portrait is” by invoking Roland Barthes’s distinction between what is denoted and what is connoted in a photograph. Gonzalez-Torres described the latter as “what we, because of our social/cultural/gender/economic background can ‘read’ into the picture.” He then revealed the intention behind much of his conceptual work: “I give the viewer a very coded word, image, moment and I hope the viewer will be able to provide then an ‘image.’” Those coded words or images might be news clippings, old photographs, or allusions to current events. Exactly what might be conjured for the viewer—a person, or an event, or one’s own experience—is left unsaid. That embrace of indeterminacy also drives the interactive quality of some of his installations, the stacks of prints and piles of candy that viewers can take from and that curators and private owners must endlessly renew.

Gonzalez-Torres mandated that his text-based portraits be situated at frieze height, near the tops of walls, and that the font used be Trump Mediaeval. The consistency of the style, rather than the presence of handmade marks, conveys authorship, while the positioning of the texts recalls news tickers and stock tickers in public spaces, as if Gonzalez-Torres were rewriting the history of the time in which he lived. His written instructions also state that the owners and other caretakers of the pieces can alter them; over the years many people, including me, have been able to rewrite the texts, adding and deleting words or phrases.

The Smithsonian show includes three of the artist’s photostats from the mid-1980s, small black pieces that feature text in white italics, in which he began to experiment with combining dates and references to historical events—for instance, “Alabama 1964 Safer Sex 1985 Disco Donuts 1979 Cardinal O’Connor 1987 Klaus Barbie 1944 Napalm 1972 C.O.D.”—to create portraits of a moment. In his dateline portraits, references abound to the AIDS crisis, to wars and social upheaval, to technological innovations and legal decisions, to popular culture and crucial moments in his own life or the lives of his subjects. They are terse and at times recondite, including phrases like “Poland 1939,” or “Supreme Court 1986,” or “miniskirt 1965,” or “Interferon 1989,” or “Trickle Down Economics 1984.”

Yet the Smithsonian curators—taking advantage of the liberality of his instructions—have added phrases to some of the dateline portraits that make Gonzalez-Torres seem invested in identity politics to a degree that he never was, and interested in explicitly addressing the subject of Cuba, which he did sparingly and always in relation to his family. These new phrases include “Return to Cuba 1979,” “Pedro Zamora 1994” (the Cuban refugee, television personality, and teen AIDS educator, with the year he died), “Cuban antigovernment protests 2021,” “American Flag Raised in Cuba 2015” (the reopening of bilateral relations during the Obama administration), and “Battle of San Juan Heights 1898” (a decisive victory for American troops in Cuba during the Spanish-American War). Gonzalez-Torres argued against having his work classified as Hispanic (the term he used rather than “Latino”). Some of Franco and Ickes’s interpretations also seem to overstep, suggesting, for example, that his use of candy might be tied to his having been born in Guáimaro, a Cuban town with a sugar mill, which is hardly convincing since the island was the world’s largest sugar producer until the 1960s, with mills in every province.

The Smithsonian’s efforts to foreground his birthplace may be related to support the exhibition received from the Latino Initiatives Pool, administered by the National Museum of the American Latino. This runs counter to a long-standing tendency to downplay Gonzalez-Torres’s Cuban origins, and it produces a surprising tension in the show. The European and American critics who have championed him since the 1990s never attempted to interpret his work as anything other than American. That desire to disassociate him from what was perceived as “Latino” was expressed in a variety of ways, from insisting on the artist’s rejection of stereotypical representations of Caribbean culture, to avoiding mention of the works that he made in Puerto Rico, to omitting comparisons to other Latin American artists or art traditions, to claiming that Gonzalez-Torres wanted to be thought of as American, not Cuban or Latino.

In a 2016 monograph the critic Robert Storr celebrated him for nimbly evading the category of “Latino artist.” Tim Rollins in a 1993 interview jokingly mentioned that there was “grumbling” about the lack of explicit Latino content in Gonzalez-Torres’s work, to which he replied with laughter and promises to make sculptures with maracas next. The decision to excise from his officially recognized oeuvre the early works that deal with his family, tourism, and Latin American popular culture could also be interpreted as part of his strategic “Americanization” (though some dispute that this decision was made by Gonzalez-Torres himself). Since his death he has been almost universally canonized as an American artist, which some have suggested is tied to ensuring the meteoric rise in the market value of his artworks.

This tendency fails to recognize that he imagined himself as an outsider who managed to slip into the American art world by means of subterfuge. As he once put it, “I want to be a spy, too. I do want to be the one who resembles something else.” Although Gonzalez-Torres exhibited in Puerto Rico well into the 1980s; had his first solo exhibition in New York at the Cayman Gallery, which was devoted to Latino art, in 1983; agreed to show his work with Cuban artists in Mexico in 1991; and enjoyed fruitful relationships with Cuban exile collectors, scholars, and curators, he evinced deep skepticism about the reductive visions of Latin American culture that prevailed in American cultural institutions and policies. As he put it to Rollins:

I have my own agenda. Some people want to promote multiculturalism as long as they are the promoters, the circus directors…. As in a glass vitrine, “we”—the “other”—have to accomplish ritual, exotic performances to satisfy the needs of the majority.

While American critics have frequently noted Gonzalez-Torres’s rejection of such labels, I can think of none who acknowledged that the New York art world of the 1980s was decidedly Eurocentric and that stereotypes about “Hispanic” art reigned unquestioned among art-world cognoscenti. There was little knowledge of Latin American literature or conceptual art or abstraction; “Hispanic” art was equated with brightly colored figurative paintings of exotic scenes or personal stories. Gonzalez-Torres never denied his origins. What he did was reject—as have many well-educated Latin American artists who, like him, immigrated to the US as adults—the American stereotypes of Latin culture that the mainstream art world relied on. As he told Rollins:

I don’t know the ghetto, I have never lived in the jungle, and I despise altars. I grew up in San Juan, which is like a small New York City without subways. So, when people say, “Oh, you should be doing this, you should be looking like that,” I really think that expectation comes from guilt, it comes from expecting us to wear grass skirts…. These assumptions are rooted in ignorance and in a condescending attitude.

Despite the fascination that his work holds for later generations of Cuban artists on the island, who embrace him as a fellow countryman, during Gonzalez-Torres’s lifetime any attempt by a Cuban exile to claim the title of “Cuban artist” would have been contested politically, since the revolutionary government maintained that national identity belonged only to those residing within Cuban territory. His college years in Puerto Rico in the late 1970s coincided with nationalist agitation led by independentistas who felt little fondness for Cuban exiles on their island, which could have troubled any attempt by Gonzalez-Torres to identify as borinqueño. His skepticism about identity politics and his sense of himself as an outsider, however, do not mean that his work shows no signs of his engagement with Latin American culture, his bilingual consciousness, his emotional identification with Caribbean geography, or his odyssey as an exile, a condition that is still very much a part of modern Cuban life.

Gonzalez-Torres shared a philosophical interest in language with Jorge Luis Borges and a sustained focus on love and death that recalls the poetry of Federico García Lorca. His attempts to democratize the circulation of his works—by creating multiples, by inviting viewers to take parts of them away, and by instructing curators and collectors to modify them—resemble the efforts of such Latin American conceptual artists as Cildo Meireles and Eugenio Dittborn. His repeated use of celestial blue and his photographs of sand, calm seawaters, and vast open skies evoke the part of the world he hailed from and returned to in his final days. He chose shades of blue that he identified as “Caribbean—saturated with bright sunlight,” as he told Rollins. He often used those colors to suggest memory and, at another level, lost love: “For me if a beautiful memory could have a color that color would be light blue.” The Spanish word for sky—cielo—also means heaven, and the phrase mi cielo, or “my heaven,” is a common term of endearment. The artist’s blue, or his sky and his heaven, can be seen as a recurring elegy to a departed lover, or to a childhood memory of parental affection.

The walls of the Smithsonian gallery devoted to his postcards and correspondence are painted blue, signaling entry into an intimate space, and one of the postcards on display has a simple drawing made by the artist of a small house, two palm trees, and waves with the word “Cuba,” suggesting a memory of home. Gonzalez-Torres noted the influence of structuralist and poststructuralist theories of language on his work—“I must say that without reading Walter Benjamin, Fanon, Althusser, Barthes, Foucault, Borges, Mattelart, and others, perhaps I wouldn’t have been able to make certain pieces, to arrive at certain positions”—and his American critics have explored his relationship to those writers. But it’s rarely remarked that he spent most of his life contending with the absence of those closest to him, both his family members and his lovers. He created the most unforgettable artistic expressions of mourning to emerge from the AIDS crisis, but these were also suffused with his early experience of loss.

Sent into exile from Cuba with his older sister at the age of twelve, Gonzalez-Torres did not see his parents or his other two siblings again for nearly a decade. (Like thousands of other Cuban children in the 1960s and early 1970s, Gonzalez-Torres was sent away to avoid Communist indoctrination and obligatory military service.) The profound impact of that separation is the subject of one of his early videos, which is not considered part of his mature oeuvre, though its title—10 horas, 10 años, 10 madres—was added by the Smithsonian curators to the dateline portrait “Untitled” (Portrait of MOCA). In the video Gonzalez-Torres writes and draws on a blackboard while he recalls his departure from Cuba and suggests that the priests who received him misled his parents.

During this part of his childhood Gonzalez-Torres’s closest relationships became restricted to words exchanged in letters, and he remained a prolific and often passionate correspondent throughout his adulthood. Letters and postcards eventually made their way into his work: fragments of correspondence with his longtime partner Ross Laycock, for example, appear among the diminutive jigsaw puzzles (all measuring seven and a half by nine and a half inches) that Gonzalez-Torres made between 1987 and 1992. The puzzles were commercially produced, with the images (also commercially produced) provided by the artist. One of their titles, “Untitled” (My Soul of Life), a somewhat awkward English rendering of the phrase el alma de mi vida (which means “my heart and soul” or “my reason for being”), signals the intensity of Gonzalez-Torres’s letter writing. The fifty-five plastic-wrapped puzzles also depict family photos, snapshots from holidays, and news clippings that together map his peripatetic existence, as he moved from Madrid to San Juan, New York, and finally Miami, with additional sojourns in Toronto, Los Angeles, and several European cities. The Spanish word for puzzle (rompecabezas) literally translates as “head breaker,” suggesting a painful struggle to manage difficult emotions as well as the artist’s effort to form an image from the puzzle’s fragments.

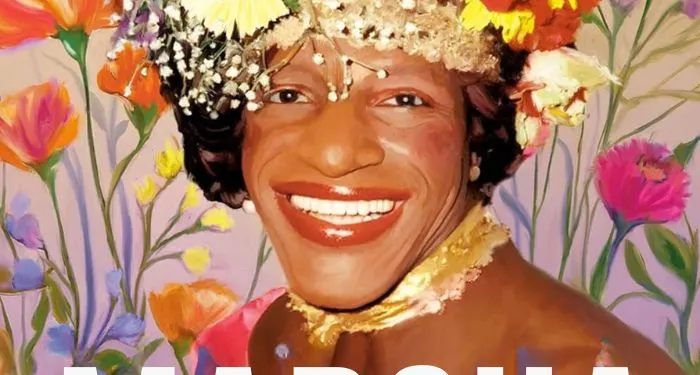

The two works in the Smithsonian exhibition composed of sweets were made in 1991, the year that he lost both his father and Laycock, who died of AIDS-related complications. “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) consists of a pile of multicolored hard candies, the ideal weight of which is 175 pounds—corresponding to Laycock’s weight. For “Untitled” (Portrait of Dad), the artist chose white mints in clear wrappers. The shapes of the piles vary depending on location, because Gonzalez-Torres gave instructions that allow for a range of interpretations: they have been presented as triangular configurations in corners, accumulated along the edges of a room, or laid out like carpets across floors. At the Smithsonian, the multicolored candies run along the bottom of the wall in one room, while the white mints form a small dome in the middle of another.

There has been much speculation about the significance of Gonzalez-Torres’s use of candy: Storr suggested that the invitation to consume these installations entails a sucking action akin to performing oral sex, while others, as mentioned, have dwelled on the medium’s sugar content as a reference to the artist’s Cuban origins. While these interpretations are plausible, Gonzalez-Torres tended to concentrate on love and loss, not sex, in his depictions of gay relationships, and his references to Cuba were largely defined by family ties. The candies may also allude to transubstantiation: by ingesting the sweets, we dissolve the boundary between ourselves and the work, altering the form of the pile, the quantity of its substance, and our own bodies as well. Gonzalez-Torres was deeply skeptical of organized religion, but having attended Catholic school in Puerto Rico, he was intimately familiar with the liturgy and church rituals.

Gonzalez-Torres is celebrated for his embrace of malleability, yet not every modification of his work has been received with equal enthusiasm. In 2022 the Art Institute of Chicago exhibited the candy pile “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) for the first time since 2018, with a revised wall label that omitted mention of the artist’s partner. A Twitter post from an incensed visitor was retweeted almost four thousand times, stirring a controversy that eventually led to the museum’s restoration of the reference to Laycock in the wall text. Recent installations of the artist’s works have at times assumed monumental proportions—for example, the translucent blue curtains of “Untitled” (Loverboy) (1989) were doubled in height and multiplied to cover sixteen windows at Dia Beacon (on view until June), a mounting that was technically possible because of his open-ended instructions.

Seeing Gonzalez-Torres’s work rendered at that gargantuan scale feels odd to those who remember the earlier, humbler iterations. The Smithsonian’s attention to the original size of his installations feels refreshingly faithful by contrast, though its interpretations are too reductive for his allusive and ambiguous pieces, forcing them into frames that feel too literal. In his brief but brilliant career Gonzalez-Torres managed to defy the conventions that circumscribe aesthetic experience and cultural identity. That was his way of speaking truth to power.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·