People like playing with string. The wheel gets more press as an invention, but the loom predated it by millennia; the Paleolithic humans who hunted mammoths also tied nets. My great-grandmother tatted, my grandmother embroidered, my mother had a fling with macramé, my generation knits. Meanwhile the menfolk were busy braiding leather, splicing rope, and mastering clove hitches. Some of this effort kept our heads from freezing and our sails from luffing, but much was clearly surplus to requirement.

In his magisterial The Ashley Book of Knots, first published in 1944, Clifford W. Ashley placed a tiny, top-hatted burlesque dancer beside diagrams of those knots deemed “purely ornamental,” but one person’s ornament may be another person’s art. And though fabric lacks the staying power of stone, enough has survived the centuries to show that textiles around the globe have acted as votive containers, social signifiers, carriers of memory and belief—instruments for making ourselves and our surroundings more beautiful and cosmologically attuned.

In the long European campaign to distinguish art from craft, however, woven images ended up on the “decorative” (i.e., nonmeaningful) side of the fence. Painting—first on panel and then on fabric—went its highbrow way, expressing ideas unimpeded by the demands of warp and weft. It is true that the Vatican spent more on Raphael’s Sistine Chapel tapestries than on Michelangelo’s frescoes, but the tapestries—woven to replicate the artist’s vast scenographic drawings of the lives of the apostles Peter and Paul—were textiles playing by the rules of painting. Then, in the early years of the twentieth century, something peculiar happened: painting—and sculpture and installation art and what have you—began to play by the rules of weaving.

This is the hidden-in-plain-sight revelation of “Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction,” an ambitious exhibition curated by the National Gallery’s Lynne Cooke, now at the Museum of Modern Art (and previously seen at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the National Gallery in Washington, and the National Gallery of Canada). Don’t be put off by the title. Its purview stretches from Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s glittering geometric beadwork (1918) to Analia Saban’s glittering circuit-board Copper Tapestry (2020), with space for Agnes Martin’s ascetic sublime, Jeffrey Gibson’s eloquent excess, the numinous painted grids of Jack Whitten, and the Arte Povera tangles of Marisa Merz. It is hard, on the evidence, to refute Cooke’s contention that “the history of twentieth-century art cannot be told apart from its intersections with thread and fiber, cloth and clothing,” though that is exactly what standard histories of modern art have done. In addition to its many visual pleasures, this is a show with some grit.

For early modernists eager to rethink the world from first principles, textiles had multiple attractions. Folk weavings were admired for what was perceived as atavistic integrity, unencumbered by stilted academicism or the egregious ornament of the bourgeois parlor. (Paul Gauguin was hanging striped blankets on his walls when he was still a successful futures trader.) At the same time, textiles were integral to the new technological society: in the eighteenth century the spinning jenny had been the harbinger of industrial revolution; in the nineteenth, the Jacquard loom paved the way for Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine and the first inklings of a future cybernetic world. Then there was the loom’s orthogonal grid, which fit nicely with new ideas of geometric abstraction in art.

The color shapes of Taeuber-Arp’s drawstring bags and cross-stitched wall art never settle into anything as predictable as a pattern. Bumping and jostling, they convey the explosive delight of Dada in its Cabaret Voltaire infancy in Zurich (she was an active member), as well as the ideals that led her to train as a textile designer. All those lovely curves and corners were infused with reformist zeal: “I believe the urge to make the things we own more beautiful is a deep and primeval one,” she wrote; true beauty grew “organically” from the object. Arbitrary, tacked-on ornamentation was “repulsive.” It was an ethos equally applicable to wall and wardrobe.

Sonia Delaunay saw “no gap” between her abstract paintings and her “so-called decorative work,” represented here by couture dresses in bright block-printed silk. The Russian avant-gardist Lyubov Popova, on the other hand, publicly renounced most easel painting to devote her energies to the new Soviet masses, transferring a sensibility honed by Cubism to her interlocking geometric patterns for the First State Textile Printing Works in Moscow (using cotton, not hand-printed silk).

The ideological middle ground was staked out by the Bauhaus, where Kandinsky filibustered about the spiritual in the painting studios while women in the weaving studios investigated the practical and aesthetic properties of fibers. Wall hangings designed by Anni Albers and her colleague Gunta Stölzl employ similar palettes and designs—vertical color blocks and horizontal bars that intersect like deconstructed tartans—but where Stölzl’s woolen Weaving (1928) exudes gemütlich homeyness, Albers’s Wall Hanging (1925) moves between silk, cotton, and acetate to produce an effect like featherweight stained glass, opaque and translucent by turns.

The matter-of-fact titles appended to these works are representative of a particular kind of ambition. These artists “trod a fine line between making a thing that hangs on a wall, as a painting does, but which might equally serve as—or be very similar to—a tablecloth or rug,” Briony Fer writes in the catalog. Albers went beyond accessories to posit a woven architecture of “pliable planes.” Her Free-Hanging Screen (circa 1948) room divider takes the form of an elegant arrangement of walnut slats and waxed cord meant to be looked both at and through.

You can see the loom logic in all of this, but while these rectilinear designs reflect the mechanism, they weren’t ordained by it. The great Indian and Persian textile traditions bloom with paisleys, after all, and when Ada Lovelace described the Analytical Engine in 1843, she admired how it “weaves algebraical patterns just as the Jacquard-loom weaves flowers and leaves,” not blocks of color in a grid. The interwar profusion of right angles in European art and design evinced stylistic preferences, and those carried over into media where they weren’t structural necessities. Versions of that deconstructed tartan are present in the exhibition in the forms of painting, drawing, and a panel of sandblasted glass by Josef Albers, who gave his creation an aphoristic title—Goldrosa (rose gold)—just like real art.

Perhaps that line between art and utility was too fine to last. After the Bauhaus was shut down and the Alberses fled Germany for the United States, Anni became a beacon for the fiber-curious, but postwar artists were more excited about new means of personal expression than they were about household goods. Theirs were art aspirations.

Olga de Amaral came from Colombia to study weaving at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan. Lenore Tawney had studied at Chicago’s Institute of Design (aka the New Bauhaus), but by the mid-1950s she was living and working on Coenties Slip in Lower Manhattan, part of an avant-garde that included Agnes Martin and Ellsworth Kelly. Sheila Hicks was a painting student at Yale when a class on pre-Columbian art piqued her interest in weaving; Josef Albers, then head of the department of design at the Yale School of Art, introduced her to Anni. Hicks recalls thinking that Anni’s work in the 1950s “didn’t appear to be utilitarian in any way” but instead brought “meaning and expression to this soft, pliable material.” (In fact, Albers had continued to design for industry—as did Hicks and Amaral, though for all of them those efforts occupied a different sphere from their exploratory handwrought works.)

What weaving offered was a means of manipulating space, texture, tautness, and line as material things. In painting, the image sits on a surface; in weaving, the image and the physical structure are one. In Tawney’s Vespers (1961), a nearly seven-foot-tall column of black and blue linen cords move together and apart like gothic window tracery executed by a spider. The same materials could be linear and tidy or shaggy and shambolic; they could move in three dimensions. The bundled yarns and braids of Hicks’s Peluca verde (1960–1961) don’t hang but sit in a pile and tumble over the edge of a plinth.

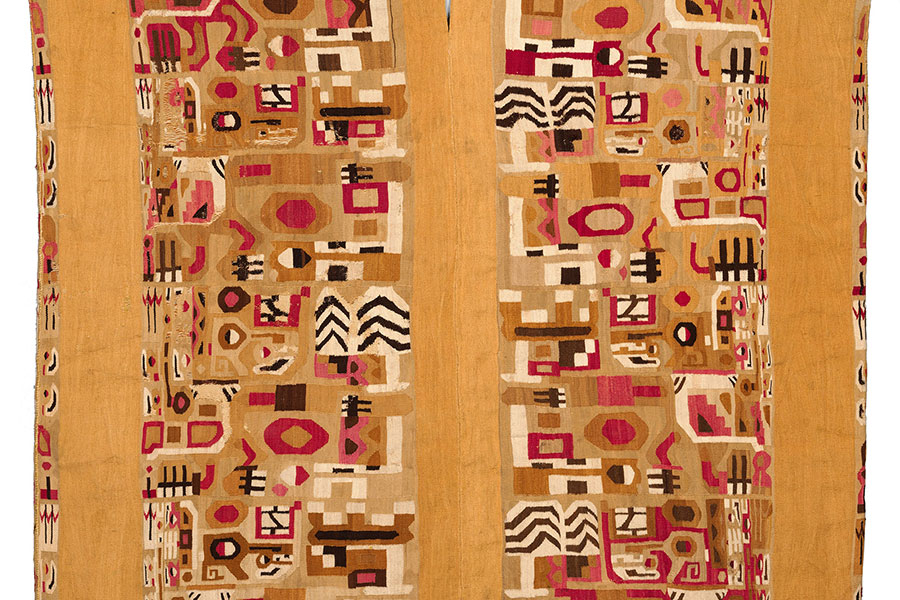

All these artists found inspiration in the extraordinary sophistication of Latin American weaving, much of it accomplished with simple backstrap looms, in which the warp is stretched between a static object like a tree and the body of the weaver, who controls tension by leaning back and forth. Amaral wrote of “the ancestral intelligence—the unconscious high mathematics—present in everything textile in ancient Andean culture.” Albers dedicated her influential book On Weaving (1965) to “my great teachers, the weavers of ancient Peru.”

As luck would have it, the National Gallery iteration of “Woven Histories” coincided with the Metropolitan Museum’s “Weaving Abstraction in Ancient and Modern Art,” a modestly sized, immodestly dazzling exhibition that brought Albers, Amaral, Tawney, and Hicks together with pre-Columbian Andean artifacts—tunics, bags and belts, woven feather wall panels. Nowhere, it would seem, have textiles been more foundational to culture. From rope bridges to the knotted-cord mnemonics of quipu, the infrastructure of Andean civilizations took form in fiber. Battles were fought with slingshots; the dead were wrapped in blankets and interred in baskets. The Inca did not lack for precious metals, yet the emperor’s crown, the Met reminds us, was a red wool fringe.

This information is not new, but knowing it is different from coming face-to-face with the startling checkerboard livery—black, white, and scarlet—worn by the Inca army that accompanied Atahualpa to his catastrophic meeting with Francisco Pizarro in 1532. Its preternatural look of modernism was shared by many items on display, like the lacy headcloth from the Peruvian Chancay culture (1000–1470 CE) in which white threads convene at regular intervals in an angular shape that closely resembles the crudely pixelated Space Invaders of old arcade games. A rollicking pattern of orbs, blocks, and squiggles on a tunic from the pre-Inca Wari empire is so intricate it required six to nine miles of thread, and so jazzy in its peppering of orange, black, and magenta it might be fifty years old rather than a thousand.

The Met’s title notwithstanding, exhibition texts make clear that many of these designs would not have been “abstract” to their intended audience. Embedded in that busy Wari pattern, it turns out, is the distorted image of a winged feline—fragmented, flipped, and repeated. That Chancay headcloth is “in keeping with formal patterns established thousands of years earlier,” whereby a single motif such as “a feline or serpent head with large eyes and a mouth” is repeated and inverted, the curator Joanne Pillsbury tells us. Pre-Columbian weavers were deploying a legible language in objects with an understood purpose, not unlike the ways the cross has been used in Christian regalia. Abstraction is not so much in the eye of the beholder as in her symbolic cosmology.

While Albers et al revered Andean textiles, the goals they set their art were different. They bypassed wearability and abjured recognizable symbols so as to give mental and visual space to the literal matter at hand: its weight, color, sheen, flexibility, presence. The reference for scale wasn’t the human body, it was the gallery (Tawney’s Shrouded River of 1966 requires a ceiling height of more than thirteen feet). They let loose ends hang like untrimmed whiskers, providing visible traces of process; they showcased unexpected substances like the rice paper and gold leaf that shimmer across the surface of Amaral’s Alchemy 13 (Alquimia 13) (1984). They let fiber be fiber. In Hicks’s The Principal Wife (circa 1965), hanks of wool, intermittently wrapped in brilliant colors, fall in heavy arcs from a bar like the reins of some Brobdingnagian horse on a festival day. It takes discipline not to reach out and give them a tug.

If the history proposed by Cooke were mainstream art history, museumgoers today would be as familiar with Tawney and Hicks as they are with Agnes Martin and Sol LeWitt. But the dominant art rhetoric (if not art objects) of the late Sixties and Seventies had eyes trained elsewhere: minimalism, conceptualism, land art. The grid appeared everywhere, but like a tradesman elevated to the gentry it was cleansed of its warp-and-weft associations. In her 1979 essay “Grids,” Rosalind Krauss pronounced it “emblematic of the modernist ambition within the visual arts” not for its connection to the everyday but for its refutation of it.

By “visual arts” Krauss really meant painting, wherein the grid served as the ultimate in abstraction: “what art looks like when it turns its back on nature.” Beyond painting, however, “Woven Histories” documents a diverse and inventive resistance to this putative disembodiment. Here the grid doesn’t turn its back on nature but offers a stage for the exercise of natural forces, especially gravity. A new fascination with the flaccid took hold.

In Eva Hesse’s 1966 Ennead, yards of brown cord sprout from a wall-mounted piece of plywood, like hair plugs aspiring to dreadlocks. Some drop straight down, while others travel in a sloppy catenary to a hook on the adjacent wall, then flop in a tangle to the floor. It is a work of inexplicable poignancy—the plain carpentry, the expansive eruption, the droop, and the casual splendor. The quixotically reinforced wire lattice of Gego’s Square Reticulárea 71/II (1971) is a lesson in distributed stress, gawky and graceful in equal measure. Alan Shields’s Shape-Up (1976–1977) occupies space in the manner of a minimalist painting, but instead of rigor we get an open crisscross of slightly slack ribbons, adorned here and there with a swag of beaded string, like postseason Christmas lights on an unkempt high-rise. Order and disorder check each other out, shake hands, and decide to get on.

Why has it taken so long for a show like this to appear? Textiles chafe against our default notions of museum-quality art—they are too entwined with the functional, the folkloric, and the feminine to be taken quite seriously. The prominence of women in “Woven Histories” is partly an expression of opportunity, especially in the earlier decades: girls were more likely to be taught needle arts and dramatically less likely to find success as painters or sculptors. (Even the Bauhaus shunted them out of the fine art and architecture tracks and into the weaving studio.) But as with the early modernist penchant for right angles, it’s also an expression of informed preferences.

In the 1960s and 1970s—when discussions of “materiality” centered on concrete and steel, and Carl Andre was blowing people’s minds by laying metal squares on the floor—something like Kay Sekimachi’s Nagare VII (1970), which is woven from monofilament (aka fishing line) and wafts in the air like a ghostly giant squid, would have been seen as simply lightweight, both physically and intellectually. In retrospect, though, these explorations of softness and openness look subversive and heroic. In the 1980s Rosemarie Trockel’s knitted paintings and sculptures would make such material-shaming their explicit subject.

While works like those of Hesse and Shields have no cognate in the universe of useful things, others preserve echoes of functionality within objects of contemplation. The curvaceous membrane and nested orbs of a Ruth Asawa hanging sculpture from 1954 bring to mind an enormous diatom made of chain mail, but up close it’s clear that the hand-looped wire mesh they are made from is a close cousin of the kind of metal basket you keep onions in. The rippling rattan of Martin Puryear’s sculpture The Charm of Subsistence (1989) has the silhouette of a flattened, off-kilter bottle, while his Greed’s Trophy (1984) appends a long tapering scoop of wire mesh to what looks like a small handle. We know this is art because of the scale—the first is the height of a basketball player, the other the height of an elephant—but shrink them down and you might be tipping them back and forth in your hand, trying to figure out what they were meant to be used for.

This brings us to baskets, which for me at least constituted the most challenging part of the exhibition. When craft-oriented artists first started messing around with them in the Sixties, baskets not only had “no profile as an art form,” Elissa Auther writes in Woven Histories, they were “barely respected as a craft form.” There was none of the technological cachet of weaving, since the process has never been mechanized; everyone has handmade baskets kicking around. That unprepossessing quality was exactly what drew certain people. For Ed Rossbach, the guiding spirit of American basketry, the appeal included new possibilities of haptic experience and volumetric structure, and also “problems of commonness, foreignness, distance, nearness, persistence, [and] impermanence.”

For indigenous artists, basketry offered a rare vector of cultural continuity. In Australia, Yvonne Koolmatrie learned Ngarrindjeri sedge-grass weaving from one of its last practitioners, and her Eel Trap (2003) and Burial Basket (2017) sit uncertainly on the slope between object of use and object of contemplation. Shan Goshorn (Eastern Band of Cherokee), who began making baskets after being hired to illustrate historical Cherokee examples, adopted traditional plaiting techniques but replaced reeds with paper reproductions of documents and photographs touching on Native history and experience, from boarding schools to treaty violations. The lovely mottled green of Color of Conflicting Values (2013) is interrupted periodically with the slivered image of a twenty-dollar bill bearing the grim visage of Andrew Jackson, father of the Trail of Tears.

Other baskets in “Woven Histories” include knobbly bundles of roots and plaited bamboo (Nagakura Ken’ichi), tumbleweed-like balls of reeds (Lillian Elliott), and crocheted opalescent polyester tubing (Katherine Westphal). Rossbach’s contributions range from the funky, rustic poise of Raffia Lace Basket (1973) to his Iridescent Cubic Basket (1990), an origami-ish structure of folded plastic sheeting.

Almost all are of a size to fit nicely on a bookshelf. Some might even hold things, which is part of what makes them so confounding as artworks. The point of a Warhol Brillo box or a Picasso jug is that it is art playing at being a regular thing, like Marie Antoinette in happy-shepherdess fancy dress. But like the beaded bags of Taeuber-Arp, baskets are often sincerely, confusingly nonbinary. One catalog essay takes her to task for having failed to break fully from her bourgeois setting or adequately acknowledge colonial violence (though most Europeans in 1918 probably had more immediate forms of violence on their minds). To my eye, however, the imperfect alignment of her creations with a given set of values—sexy and dowdy, adventurous and twee, utopian and mired in the material and economic realities of a particular time and place—is precisely what makes them worth looking at.

Few recent survey shows have been so full of objects that don’t quite fit the usual categories and make you double back to figure out what’s going on. This is not just the experience of art critics. Speeding through the National Gallery just before closing time, the tech blogger Ken Shirriff passed a woolen weaving in muted tones whose design struck him as oddly familiar. Stopping to look closely, he recognized the layout of an early Pentium microprocessor.

Replica of a Chip (1994) is the result of Intel’s commissioning of the Navajo weaver Marilou Schultz to depict their new chip using traditional methods and materials—hand-carded wool from local sheep, home-brewed dyes, etc.1 Asymmetrical and filled with glitchy scan lines and jagged color shifts, the design is more hectic than most Navajo weaving. It might even be interpreted as less “mechanical” and more “expressive” in intention, though the qualities in question are the product of Schultz’s close adherence to the magnified die photograph she was working from. Her “replica” is accurate enough that Shirriff was able to identify the specific Pentium subvariant (the P54C), even though it happened to be hung showing the reverse side. (Navajo rugs have no specified front and back, but integrated circuits do.)

There is a further backstory: before founding Intel in 1968, Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore (he of the eponymous law) were principals in Fairchild Semiconductor, which opened production facilities on Navajo land in Shiprock, New Mexico, in 1965. Promotional materials from 1969 showed Navajo weavings along with similar-looking circuits and celebrated the confluence of Navajo craft skills (patience, dexterity, precision) with the needs of semiconductor manufacture. The Shiprock enterprise eventually employed close to a thousand workers, and Fairchild touted its success for a decade, up until armed American Indian Movement activists took over the plant in a labor dispute, and Fairchild walked away.

The Shiprock saga has been told from many angles: female empowerment (most of the employees were women), labor exploitation (ditto), ethnic and gender stereotyping, and so on. Replica of a Chip makes no argument. Instead it presents us with a material quandary—a familiar kind of thing (a woven blanket) made strange by the importation of a different governing logic, one that for most of us is not quite recognizable.

The problem for “Woven Histories” is not that weaving is too niche but that it is so pervasive, so embedded in our metaphors, conceptual constructs, and daily experience of the world. Almost anything can seem related—woven things, plans for woven things, photographs of woven things, paintings that look kind of like woven things, videos about the making of woven things. It can be hard to track the thread beyond just the idea of thread.

Viewers might find videos about the textile industry interesting (or not), but they work as videos do, presenting immaterial projections of monocular views of events that happened somewhere else. The palpable immediacy of the earlier art, its challenge to customary ways of thinking about objects, evaporates into familiar modes of looking and being told what to see. This is not a slag against video: it has its own strengths as a medium, but they are time-based, narrative, and most often disassociated from any specific material, scale, or surface. What it doesn’t have is weight, sag, resistance, pliability.

Weaving, Michelle Kuo writes in the catalog, “manifests, as material, a symbolic order.” What is distinctive about this order, it seems to me, is its interdependence—everything tugging a bit at everything else. Look at Stölzl’s wall hanging or Asawa’s chain-link bubbles and this is what you see enacted in space. And walking through “Woven Histories,” you can sense a gradual change in the order of that order: the grid, with its connotations of control and stability, slowly cedes its emblematic status to the network, with its promise of resilience and accommodation to uncertain outcomes.

It doesn’t seem accidental that the Gego retrospective at the Guggenheim in 2023 prompted rapturous public response,2 or that the Ruth Asawa retrospective now at SFMOMA (it comes to New York in the fall) is one of the most eagerly anticipated shows of the year. In our current technological moment, things composed of nodes, edges, and articulated empty space resonate with us. When I read about how neural net inputs go through multiple stages of “weighting” in AI, my mental image looks a lot like a Gego sculpture. When I try to envision structures like fuzzy logic (calculations with nonbinary degrees of truth) or Monte Carlo processes (using random sampling to simulate complex systems and probabilities), I see something like Rossbach’s Constructed Color Wall Hanging (1965).

His floppy, open web is simultaneously psychedelic and orderly. Imagine a tie-dyed version of that pre-Columbian Space Invader headcloth executed while tripping. It is also eerily predictive of more recent photo-imaging of natural connective structures: biological neural networks and dark matter distribution in the universe. Like much of what’s on view in “Woven Histories,” it suggests that the world is a complicated, messed-up, sometimes beautiful place, held together by holes and tangles.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·