In the last two decades, romantasy has emerged from relative obscurity to become one of the most popular book genres among avid readers. The genre — its name a portmanteau of “romance” and “fantasy” — combines the magical elements of fantasy with the emotionally charged plotlines of romance.

Romantasy has surged in the 2020s, bolstered by vocal communities of fans who are active on BookTok and other social platforms. Indeed, authors of successful romantasy series, like Sarah J. Maas and Rebecca Yarros, carry star status among their large fan bases — drawing millions of followers on social media and massive crowds at book-signing events.

If your romantasy canon begins with Twilight and ends with Fourth Wing, you’d understandably believe that romantasy is a brand-new genre, brought into the mainstream by the diversifying effects of social media or pandemic-era tendencies toward escapism. In reality, though, romantasy has deep roots in some of the oldest works of English fiction: medieval legends.

With the TV adaptation of Fourth Wing on the horizon and plenty more romantasy titles coming in 2025, let’s take the momentum of this subgenre and turn it on its head — that is, rather than looking solely at what’s to come, let’s dig into the evolution of romantasy … starting with its centuries-old origins.

From Courtly Love to Futuristic Affairs

The word “romantasy” first came into the public vocabulary when it appeared on Urban Dictionary in 2008, but elements of the genre are as old as English fiction itself. Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, written in the late 15th century, centers on chivalric quests to win the hearts of fair ladies; these stories introduced the “damsel in distress” and “knight in shining armor” archetypes, along with fantastical monsters and villains.

Many of these early romance-focused fantasies were pretty formulaic. A beautiful woman, incapable of shielding herself from disaster, relies on a valiant rescue — from dragons, evil stepmothers, witches, etc. — by a handsome knight. Cue the violins and the happily-ever-after! This basic plot, with variations on the particulars, has proven immensely popular across generations and cultures. It repeats itself in other Arthurian legends like Sir Gawain and The Green Knight, fairytales like Cinderella, the Greek myth of Perseus and Andromeda, and nearly every Disney princess movie before Frozen.

But the combination of romantic and fantastical themes took a darker turn toward the end of the eighteenth century, when Gothic fiction writers like Bram Stoker, Mary Shelley, and Horace Walpole revived dark and haunting fantasies. Love and desire have their roles to play in these books, but they come to fruition in more complex ways than the “HEA”s of Chaucerian fiction. In Frankenstein, for example, the lonely monster begs his creator to make a female companion for him — but the eponymous doctor refuses. In Dracula, the Count takes advantage of Mina Harker’s innocence, forcing her to suck his blood to create a bond between them.

Far from the romance narratives of old, whose damsels always gleefully paired up with their saviors, Gothic novels dug deeper with themes of manipulation, coercion, and unrequited longing. Where fantastical creatures were once always villains — the thieving ghosts of The Green Knight, the alchemical dragon of The Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale — Gothic authors made them protagonists and antiheroes, questioning the implication that humans are always the most virtuous creatures.

But though Gothic fiction distanced itself from its predecessors by introducing darker themes and “grayer” characters, many of them still focused on male exploits — and here, romance served as a symbol for desire or a distant subplot, rather than taking center stage. In other words: it was still a ways off from romantasy as we know it.

The darker imagery of Gothic fiction appears in some contemporary romantasies, like Leigh Bardugo’s Shadow and Bone series, which centers themes of power, darkness, and forbidden love. But if we really want to understand how Gothic fiction grew into romantasy, we have to meet those romantic plotlines where they began: the “classic” romance novel.

Romance Begins Stealing Readers’ Hearts

While Gothic fiction was taking over in literary circles, another genre was growing popular among “ordinary” readers — romance!

Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, published in 1813, was among the first romance-flavored novels to become popular among women; previous attempts, like Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, were less appealing for their lack of three-dimensional female characters. Pride and Prejudice introduced a radical new idea to 19th-century readers: that women have complex internal lives, and even occasionally romantic desires of their own. Halfhearted pearl-clutching ensued, but the success of Pride and Prejudice made one thing clear: there was an untapped market of women readers out there who’d love to see their experiences and desires represented.

Literary romance enjoyed steady growth throughout the 19th century, but it really exploded in popularity when mass-market paperbacks hit the United States in the 1930s. As the Great Depression sent Americans looking for escapism, the genres of romance, fantasy, and science fiction all continued to grow.

By the 1980s, further improvements in printing technology and more lenient social norms triggered a second boom in romance publication. This time, the genre splintered into categories — some setting the groundwork for the romantasy that’s so popular today.

Paranormal romances, in particular, combined elements of horror and romance in ways that might feel very familiar to romantasy fans. In Annette Curtis Klause’s The Silver Kiss, for instance, a teenager grieving the loss of her mother gets caught up with a vampire who’s dealing with a similar trauma. And in L.J. Smith’s Vampire Diaries series — first published in the 1990s, long before it was turned into a TV show — young student Elena Gilbert must contend with a love triangle between vampire brothers and a series of occult incidents in her town.

Enter … The Twilight Effect

Though titles with paranormal and fantastical romance plotlines saw an uptick in publication in the 1980s and 90s, these subgenres remained niche. Authors promoted their works to small but loyal fanbases, and sold mass-market paperback copies in airports and grocery stores whenever possible — but mainstream literary media didn’t take these books very seriously.

That is, until Stephenie Meyers’s Twilight hit the shelves. The bestselling book series, revolving around the romance between human Bella Swan and vampire Edward Cullen, was originally published in 2005. It’s since inspired blockbuster movie adaptations, branded makeup collections, and fierce online debates (team Jacob all the way, sorry!) — in other words, unprecedented popularity for a horror-romance series. The first book received massive acclaim from lifelong paranormal romance devoteés and new readers alike, the movies were met with mile-long lines, and the “Vampire Renaissance” began.

The publication of the first Twilight book was quickly followed by a slew of similar paranormal romance series like Tracy Wolff’s Crave series and Maggie Stiefvater’s Shiver trilogy. Even books that didn’t feature a traditional horror creature, like a vampire or a werewolf, came to share attributes with Twilight: they starred young female protagonists, they raised questions about the nature of love between inhuman creatures, and they detailed addictive, slow-burn romances that kept us enthralled. Some books were serious, like Ilona Andrews’s Kate Daniels series; others, like Chloe Oneil’s Chicagoland Vampires series, were funny and irreverent.

Self-Publishing and the Rise of Genre Fiction

Many of these post-Twilight books were self-published or published online — methods that have continued to gain traction for the creative freedom and artistic control they allow.

Self-publishing (and its little sister, fanfiction) has contributed to much greater exposure of stories that publishing houses have not picked up historically, allowing for the popularization of ~spicy~ romances that might not have made it to mainstream audiences otherwise. Authors of romance have been especially successful with self-publishing, which has allowed them to experiment with diverse fantastical worlds and pioneer new romantic tropes.

This is where we find the humble beginnings of some of romantasy’s hottest names. Sarah J. Maas, author of the cult favorite A Court of Thrones and Roses series — whose popularity on BookTok brought romantasy to a mainstream audience in the 2020s — started publishing fiction on the website FictionPress when she was just 16 years old. Similarly, New York Times bestselling author Rebecca Yarros began publishing books way back in 2014, laying the groundwork for her now-astronomical Fourth Wing series to take off. Both authors have since grown their platforms on social media, and both have fiercely loyal followings today.

Romantasy as Modern Escapism

Romantasy’s rise to prominence undoubtedly reflects contemporary cultural dynamics — and, in my opinion, has shaped them as well. The genre has transformed the literary landscape by introducing unprecedented emotional depth and centering interpersonal relationships, expanding the definitions of both romance and fantasy.

Reading romantasy has also become a powerful form of escapism in an era marked by existential unease. As a host of global crises — ranging from climate change to political instability to the impending threat of another pandemic — grow scarier by the minute, these novels offer a sanctuary. They transport readers to alternate universes where the rules of reality bend to the transformative power of magic and love. Strong themes of justice and successful resistance efforts may be comforting to readers who see similar efforts go unrecognized IRL. And fictional intimacies, forged in struggle, might feel more real than the endless scroll of anonymous faces on dating apps.

Of course, when reading about a world where resisting oppression is not just possible, but celebrated, it’s frustrating to be pulled back into our unjust reality by signs of racial stereotyping or gendered injustice. Some readers have criticized Sarah J. Maas’s use of “male” and “female” — important identity terms in ACOTAR — as upholding a regressive gender binary. Elsewhere, critics have argued that her books — and others in this genre — glorify or dismiss abuse, lack diverse representations of romance, and draw on harmful racial stereotypes.

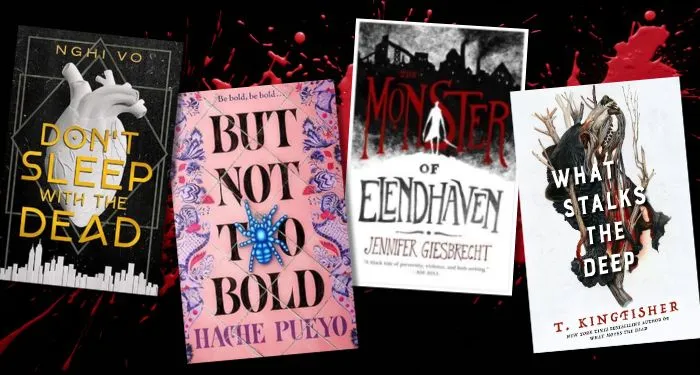

Beyond these blockbuster books, though, authors of romantasy are cooking up storylines that offer diversity in all its forms. S.A. Chakraboty’s The City of Brass features vivid depictions of an 18th-century Cairo in which creatures of Middle Eastern mythology have come to life. Natasha Ngan’s Girls of Paper and Fire explores themes of systemic oppression, personal autonomy, and resistance through its protagonist’s struggles against a political system that treats women as objects. Elsewhere, you can find romantasies that challenge traditional views on gender, monogamy, and warfare.

Though its most popular books might still evoke some problematic stereotypes, others truly fulfill the escapist promise by bringing readers into diverse worlds where fights against oppression often succeed.

The Future of Romantasy

I’m personally very excited about where the genre seems to be heading — embracing diversity, using fiction to comment on real social issues, and building complex magical worlds that serve as both sanctuaries and mirrors.

I also hope that self-publishing continues to grow in legitimacy and remove barriers to entry for aspiring romantasy authors. The number of authors and the volume of work that’s published each year is already increasing, especially (and most excitingly!) in this genre.

And I’m eager to see what new digital platforms and literary technologies bring to the scene — for my part, I’m hoping for more interactive novels, audiovisual novels, and other forms of romantasy that push the boundaries of what a novel can be. Overall, I really can’t wait to see what happens next in romantasy — and, with any luck, to get to write about it.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·