The Aldobrandini Tazze, as they are now known, are a set of twelve shallow silver dishes on pedestals, resembling cake stands. Engraved on the interior of each dish are scenes from the career of an early Roman emperor (Julius Caesar to Domitian). In the center of each stands a silver statuette of the ruler, about the same height as the pedestal below, so that the whole resembles a spinning top about eighteen inches tall. The set is first recorded in 1599 and must have been created not too long before that; its modern nickname comes from an early owner, the Roman cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini. We do not know who made it, where it was made, or what exactly it was used for.

Fatally, the emperors could be unscrewed for cleaning. And once they were all lined up in a row, neatly polished, it would have taken considerable knowledge to get each emperor back on the proper plate. By the time the set was dispersed, following an 1861 auction, emperors and plates were all mixed up: Nero is now on Augustus’s plate in Los Angeles, Galba on Caligula’s plate in Lisbon. A three-way swap between museums in the 1950s tried to restore Otho, Vitellius, and Domitian to their proper homes—with only partial success, since the plate then thought to be Domitian’s, in the Victoria and Albert Museum, actually shows scenes from the life of Tiberius.

Such misadventures are one subject of Mary Beard’s Twelve Caesars, the revised and expanded version of the A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts she delivered in 2011 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Beard, a now retired Cambridge don, is probably best known to popular audiences from her 2015 history of Rome, SPQR, as well as her many television appearances. She is also the author of important studies of Pompeii, the Roman triumph ceremony, and the Colosseum (the last in collaboration with Keith Hopkins).

As Beard’s work has constantly emphasized, our understanding of antiquity is mediated by previous observers. Think of the words Roman gladiators cried at the start of all their matches: “Hail, Caesar! We who are about to die salute you!” Or so we like to imagine. The acclamation shows up in almost every Roman movie, but it gained its modern currency from the title of an 1859 painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme. Gérôme got it from an ancient biographer who records that one batch of gladiators addressed it on one occasion to the emperor Claudius (who with typically awkward humor responded, “Or not”). The words now stand as a kind of collaboration between the first century and the nineteenth: not invented, yet not quite authentic either. For Beard, though, the meanings that later observers have extracted from antiquity are no less real or interesting when they rest on misunderstanding, wishful thinking, overeager “restoration,” or active forgery. To recreate the past is also, inevitably, to create it.

Beard’s title Twelve Caesars evokes those rulers whose lives were written by the early-second-century biographer Suetonius. (He is the source who preserves that “Hail, Caesar!” anecdote.) Suetonius’s work covers the Julio-Claudian dynasty, from Julius Caesar (not quite an emperor, but close enough) to Nero. It then turns to three losers in the civil wars of AD 68–69, Galba, Otho, and Vitellius, and the eventual winner, Vespasian, with his two sons and successors, Titus and Domitian. But Beard is less interested here in the actual Caesars than in their visual representation, both in antiquity and after.

She begins with a question that often goes unasked: How do we know what a given emperor looked like? Suetonius gave terse physical descriptions, not always easy to parse or to link up with extant imagery. Emperors evidently sat for official portraits, like presidents. Copies of the resulting busts circulated throughout the empire—though one might wonder if the brief reigns of Otho or Vitellius allowed time for this, or whether their subjects were eager to keep their portraits after they were overthrown. Surviving busts are rarely labeled, and some conventional identifications rest on shaky ground. Emperors also put their own visages on coins, which survive by the tens of millions. From the Renaissance to the nineteenth century it was these, above all, that transmitted the imperial image.

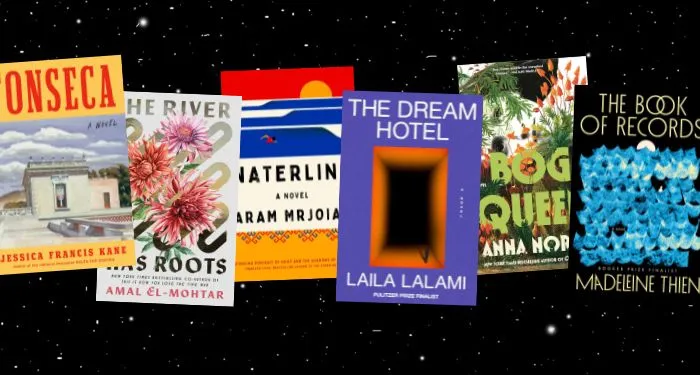

In modern times the Caesars have appeared in diverse forms: statuettes, paintings, prints, tapestries, medallions, ceramic plaques. We regularly find a canon of twelve emperors, as in Suetonius—though not always Suetonius’s twelve. Prone to drop out were the depraved Caligula and the colorless Titus. Additions might include various “good” rulers of the second century: Trajan, Hadrian, or Antoninus Pius. Some collectors were more ambitious. Louis XIV’s sister-in-law, the German princess Elizabeth Charlotte, assembled a complete run of emperors on coins, from Augustus to the early-seventh-century Heraclius. (“Collect the set!”)

Perhaps the most imposing assembly of Caesars is in the Capitoline Museum in Rome, whose “Room of the Caesars” houses a collection of busts first formed in the 1730s. As Beard describes it:

The whole range of imperial portrait types here, almost literally, rub shoulders—from some bona fide ancient pieces (rightly or wrongly identified as imperial characters), through heads that have been artfully “restored” into an emperor or imperial lady, hybrids of all types (including some genuine ancient faces inserted into flamboyant modern multicoloured busts), to any number of modern “versions,” “replicas” or “fakes.”

The emperors’ heads are images of eternity, yet as a group they remain in flux, subject to addition, subtraction, and periodic rearrangement.

The most famous modern Caesars were a set of eleven (omitting Domitian) by the Venetian master Titian. Painted in the late 1530s for the Gonzaga family of Mantua and subsequently acquired by Charles I of England, they ultimately made their way to Spain, where they were destroyed in a 1734 fire at the Alcázar palace in Madrid. Our knowledge of them depends on secondary sources: copies, drawings, descriptions, and inventories. In their original setting they were complemented by panels depicting scenes from the emperors’ lives, the work of Giulio Romano and his workshop; several of these still survive.

The tale of Titian’s Caesars, “dogged for centuries by puzzles, inconsistencies, optimistic inferences and modern mistakes taken as ‘facts,’” is tailor-made for Beard, who shows how the meaning of the ensemble changed over time as it moved from court to court, as its surroundings altered, as the set itself began to mutate. (The “missing” Domitian was inevitably supplied; Van Dyck was hired to touch up Galba and replace a badly damaged Vitellius.) The influence of the originals was vastly multiplied by a set of engravings made around 1620 by the Flemish printmaker Aegidius Sadeler. Well into the nineteenth century, and often at many removes, it was still Titian’s emperors who held the field. (Sadeler produced a companion set of imperial wives, but it never really caught on.)

Not all portrayals implied admiration. Sadeler’s engravings came with Latin verses on the Caesars, most of them highly critical. A caustic satire on his own predecessors by the fourth-century emperor Julian inspired an over-the-top mural on a staircase at Hampton Court. A now lost set of tapestries commissioned by Henry VIII featured Julius Caesar—but as Beard brilliantly reveals, it was designed to illustrate the anti-Caesarian epic Pharsalia by the Neronian poet Lucan. Nineteenth-century history painters were fascinated by the elder Agrippina, who defied Tiberius, and also by imperial assassinations: the 1847 Prix de Rome competition generated ten different versions of Vitellius’s end. Beard rightly wonders what Vasily Smirnov’s 1887 canvas The Death of Nero signified to its owner, Tsar Alexander III.

The gravity field of the Caesars is so powerful that it has drawn into its orbit some figures who may not be Caesars at all. The fence around the seventeenth-century Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford is surmounted by fourteen bearded heads regularly referred to as “the Emperors.” According to Beard that label can be traced back no further than Max Beerbohm’s 1911 novel Zuleika Dobson, though it may predate the book by a few years. Nor are the heads themselves all they seem: the originals have been replaced not once but twice, in 1868 and in the early 1970s. Beard reports that a couple of the originals are still in use as lawn ornaments in Oxford.

For all the variations, Suetonius’s canon has shown impressive staying power. His Twelve Caesars took their place with other conventional groups: the Seven Wonders, the Nine Worthies, the Ten Commandments. The Suetonian dozen offered both unity and variety, from the far-seeing statesman Augustus, who reigned for more than four decades, to the hapless Otho and Vitellius, with their few sad months in the purple. Individual Caesars supplied a standard to measure one’s own ruler against, or a moral lesson for the ruler himself. (“Be an Augustus, not a Nero!”) As an ensemble they invited one to think about dynasties: their formation, their persistence, their sudden and violent ends.

It is not just moderns who have found the emperors good to think with, as Beard’s most recent book shows. Emperor of Rome returns us (mostly) to antiquity. Its focus is the imperial period from Julius Caesar to the early-third-century Alexander Severus, with brief appearances by later rulers.

Modern impressions of the emperors tend to track the image of “good” and “bad” monarchs as portrayed by senatorial historians like Tacitus. The good emperor (Augustus, Claudius, Vespasian, Trajan) is a modest man who takes his office, though not always himself, seriously. He treats the Senate with respect, inviting senators to dinner and promising not to execute them without trial. Mostly he keeps that promise. He may engage in some limited conquest—enough to enrich the empire without draining its manpower. His building projects benefit the masses: new forums, harbors, amphitheaters, baths. When he dies in his bed he leaves a full treasury and is succeeded by a grieving son (often adopted), who sees to his official deification.

The bad emperor is another story. He executes senators right and left, performs on the stage, spends wildly on himself. His building is self-indulgent: grandiose projects soon abandoned, private palaces, a pontoon bridge to let him ride across the Bay of Naples on horseback. His wars are childish or disastrous, his triumphs make-believe. Not content with presiding over the arena, he appears as a gladiator or beast-slayer himself. He has colorful sex with inappropriate partners. His end is violent and his memory execrated. Yet he is, there is no getting around it, a more exciting figure than his virtuous colleagues. Hence his prominence in Roman movies. John Hurt’s Caligula, Peter Ustinov’s Nero, Joaquin Phoenix’s Commodus—these are the Caesars we remember.

This good/bad dichotomy is not without problems. Some reigns were too short to provide much material for categorization. And there are rulers the rubric has trouble accommodating, complicated figures who puzzled even their contemporaries: the unreadable and reclusive Tiberius, for instance, or Hadrian, restless and mercurial. On closer inspection, even the textbook cases start to break down. Claudius mixed real accomplishments with capriciousness and cruelty. Nero, loathed by the Senate, was loved by the people. An emperor’s posthumous standing depended a lot on his relationship with the elites, and with his successor.

Beard’s book is not about the emperors but the emperor. As such, it is organized thematically, not chronologically. Individual chapters show us the monarch at home and abroad, at work and at play, dining and dying. One chapter is devoted (of course) to imperial portraits, another to the perennial problem of succession. Of Suetonius’s twelve Caesars, only Vespasian passed the throne on to his own biological son; the next to do so, a century later, was Marcus Aurelius.

Obvious throughout is Beard’s delight in the diversity of sources that record imperial activity. Some of these are texts that survive in medieval manuscripts. The scholar Philo was one of a group of Alexandrian Jews who went on an embassy to Caligula. His account shows us the ambassadors trailing along after the emperor as he tours one of his properties, asking distracted questions. (“So why don’t you people eat pork?”) Seventy years later, under Trajan, the senator Pliny served as governor of Bithynia, in modern Turkey. His extant correspondence with the emperor covers subjects that range from Christians to fire brigades.

Letters between the rhetorician Fronto and his youthful pupil Marcus Aurelius were uncovered only in the nineteenth century, in a parchment manuscript imperfectly erased and reused for the records of a Christian church council. The student sends lovey-dovey greetings; the teacher reports on his multifarious ailments. The adult Marcus’s own ill health is mentioned by the superstar Greek physician Galen. In one anecdote Galen cures the emperor’s diarrhea by replacing the porridge other doctors had prescribed with an anal suppository and pepper-laced wine. “That’s it! That’s it! That’s it!” cries the delighted monarch.

Many emperors were writers themselves, though few of their works have survived. We have a little of Hadrian’s (mediocre) poetry. Claudius’s lost history of the Etruscans would surely have made interesting reading; so would Domitian’s treatise on hair care. One text we do possess is Marcus Aurelius’s spiritual journal, now known as the Meditations. Beard has no very high opinion of it: “A collection of philosophical platitudes, one of those books now more often bought than read.” This is an odd thing to say of a work that has never had as many readers, for better or worse, as it does today.* While it throws little direct light on the ruler’s day job, its repeated complaints about the tiresomeness of people surely reflect his experience on the throne. More superficially informative is the Res gestae divi Augusti (The Achievements of the Divine Augustus), the first emperor’s accounting of his own rule, intended for display on his tomb and preserved in an inscribed copy found in Turkey. A deeply disingenuous document, it needs to be read for what it does not say as much as for what it does.

The Res gestae is one example of the epigraphic habit, as it has been called. In the early imperial centuries Romans—not all of them wealthy or powerful—felt an apparent compulsion to preserve texts by engraving them on metal or stone. On a bronze tablet found at Lyon (his birthplace), Claudius lectures the Senate on the need to admit Gaulish aristocrats to its number. (Tacitus gives a version of the same speech, helpfully rewritten.) From Rome itself we have inscribed epitaphs of the emancipated men and women who worked for Augustus’s wife Livia. Graffiti from the service quarters of the palace provide early evidence of Christians among the staff.

At Aphrodisias, in Turkey, a whole wall at the entrance to the theater is given over to inscribed documents, including imperial letters—one from Hadrian, for instance, exempting the city from a tax on nails. The well-traveled Hadrian shows up elsewhere too. An Algerian inscription records his speech to soldiers there, like a headmaster commending students at graduation. (“You have filled the plain with your manoeuvres, you have thrown the javelin not inelegantly….”) A papyrus memorandum from Egypt lists items requisitioned for his upcoming visit to the province: 372 suckling pigs, ninety kilos of unripe olives, and so on. A fragmentary poem by one Pankrates shows us the emperor off the clock, out hunting with his paramour Antinous.

One influential view of the emperor is that associated with the Oxford historian Fergus Millar. In The Emperor in the Roman World (1977), Millar famously argued that “the emperor was what the emperor did.” And what the emperor did, overwhelmingly, even on the road, was answer his mail. He received embassies from provincial elites, accepted or declined honors from cities, judged criminal cases, fielded appeals for tax exemptions, reviewed reports and accounts, answered legal questions from individuals, approved or rejected the actions of provincial governors, and reacted to abuses by issuing new edicts or reiterating old ones that had been ignored.

There were practical limits on his power. It took time for mail to reach the court, and time for the response to go back. And the Roman civil service operated with a skeleton staff. Imperial China, Beard notes, “had proportionately twenty times more senior administrators than did Rome.” Many services and functions were privatized, with all the corruption and inefficiency that implies. Peaceful provinces like Pliny’s Bithynia were governed by senators with little local knowledge, serving short tours. Some were expert mainly at taking bribes; none had much in the way of enforcement power. The legions were concentrated on the frontiers: in Britain and Germany, along the Danube, and in the East. Those too were headed by senators; the Roman army had no general staff or professional officer corps. Here, at least, the emperor needed competent men—but not too competent, or too ambitious. Emperors could be made elsewhere than in Rome.

In courts, what matters is not one’s official job title but proximity and access to the monarch. The powerful person is the one who can lay your case before the emperor or put your nephew’s name forward for a post, the right person to bribe for a lucrative contract. One of Beard’s chapters is devoted to “Palace People.” It deals with the cloud of figures in orbit around the emperor: wives and other female relatives; secretaries, tutors, doctors, and all-purpose courtiers; imperial slaves and freedmen. Suetonius had been a palace person; before writing his Caesars he headed Hadrian’s correspondence department.

All these people were, in some sense, the power behind the throne. (Personnel is policy, as they say.) Aelius Sejanus commanded the Praetorian Guard under Tiberius. More importantly, he had the emperor’s ear. When the emperor retired to Capri halfway through his reign, it was Sejanus who effectively ran Rome. All right-thinking people loathed him—after he fell from favor.

Sejanus was at least a male aristocrat. Claudius was ruled by his wives and freedmen, or so it was resentfully believed. Stories circulated of Messalina’s voracious sexual appetite, of the younger Agrippina’s incestuous relations with her son, Nero. The disdain the senatorial class felt for the once enslaved ministers Pallas and Narcissus sears the pages of Tacitus. The supposed maneuverings of palace people—who’s up, who’s down—have always found a ready audience. Americans can slot in their own set of names: Vance and Musk, Melania, RFK Jr., Steve Bannon, Jared and Ivanka.

Millar was not interested in palace gossip. He wanted facts. His six-hundred-page study gutted documents and anecdotes for hard content, discarding the rest like empty peanut shells. Beard is after something rather different. A phrase that crops up throughout the book is “true or not.” True or not, a story points to something important. True or not, a witticism reveals unspoken anxieties. For Beard, the emperor was not just what the emperor did, but what he is said to have done, or said to have said.

Such agnosticism allows her to exploit even sources known to be unreliable. One is the Historia Augusta, a sequel to Suetonius compiled in the late fourth century. Its unidentified author poses, for reasons unclear, as six different biographers writing several generations earlier. The biographies mix fact and often ludicrous fiction, like the story of Heliogabalus (definitely a Bad Emperor) crushing his dinner guests to death beneath piles of rose petals. An invention, no doubt, but an eloquent one: even the favor of an autocrat can be deadly.

Like the triumph ritual or the Colosseum, the emperor emerges from Beard’s treatment as “a complicated and multilayered construction,” not all of it ancient. We see the Caesars as others perceive them: their effect on the people around them, their significance as symbols and as vehicles of power, the outrage they provoked when they were thought to be doing it wrong. But what was it like to be Tiberius—or Titus, or Trajan? That, as Beard acknowledges, remains “hard to pin down.” At the heart of the book is an emperor-shaped hole.

Maybe there’s a reason for that. One implication of the good/bad model is that it mattered who was emperor. Certainly Roman historians thought so. The ruled take their cue from the ruler, they believed, and an emperor’s character determines the health and well-being of the empire. But what if it made no real difference who was in charge, just as long as someone was? After Caligula’s assassination soldiers found his doddering uncle Claudius hiding behind a curtain and thought he’d make as good an emperor as any. Perhaps they were onto something. Virtuous or vicious, to most of their subjects the Caesars were interchangeable, like the Aldobrandini statuettes. It helps, at the margins, if a ruler is engaged and competent, but great nations have survived monarchs who were senile, mad, infants, or just permanently checked out. Rulers can set a tone, but it is the palace people who keep things running.

A sculpture that crops up several times in Twelve Caesars is the bust known as the Grimani Vitellius. (It was owned by Cardinal Domenico Grimani, who left it to the Venetian state when he died in 1523.) A portrait of a jowly, oxlike middle-aged man, it served as a model for two different figures in Veronese’s Last Supper. In the seventeenth century the Dutch artist Michael Sweerts painted a golden-haired boy drawing it, the child’s innocence in implicit contrast with the emperor’s depravity. It is recognizably this Vitellius, not Claudius, who occupies the imperial box in Gérôme’s Hail, Caesar! painting.

The Grimani head supplied material not only to artists but to phrenologists and analysts of physiognomy: Vitellius’s indolence and gluttony, stressed by our sources, were visible right there on his features, in the very shape of his skull. But all is not as it seems. For the head is now thought not to be Vitellius at all but an unknown second-century figure. If we want to know what the emperor really looked like, our only guide is his coins.

Vitellius and his family are the primary subjects of Peter Stothard’s Palatine. Stothard is a former editor of The Times and The Times Literary Supplement who has made a second career of writing popular books on Rome. Crassus: The First Tycoon (2022) is a biography of the wealthy Republican politician. The Last Assassin (2020) details the fates of Julius Caesar’s killers, hunted down by the dictator’s heirs, Octavian and Antony, like the terrorists in Spielberg’s Munich. Both money and murder figure prominently in Palatine, “an alternative history of the Caesars.” Its title alludes to the hill that hosted the imperial dwelling, the source of our word “palace.” Its fifty-three short chapters follow two generations of Vitellii through the Julio-Claudian dynasty and into the long year AD 69, the “Year of the Four Emperors.”

The Vitellii were palace people par excellence. The family’s fortunes were founded by Publius Vitellius, an imperial procurator under Augustus. Of his four sons, two are of note. Publius Jr. did an undistinguished stint with the Rhine legions under Germanicus, Tiberius’s nephew and designated successor. When Germanicus died suspiciously in Syria it was the younger Publius who was tagged to prosecute his supposed killer, a job that brought more peril than glory. Having hitched his fortunes to the powerful Sejanus, he did not long survive the latter’s spectacular fall.

His brother Lucius was a more skillful operator—“a placid toad of the palace corridors,” Stothard calls him. He rose to become consul (three times), effectively serving as regent while Claudius was campaigning in Britain. As governor of Syria he got Pontius Pilate cashiered, not for executing Jesus but for “the clumsy crucifixion of some Samaritan protesters.” An adherent of Claudius’s third wife, Messalina, Lucius managed to jump ship before her demise. It was he who advised the Senate to approve the widowed Claudius’s marriage to the emperor’s own niece, Agrippina. He prosecuted his patrons’ enemies when called on, doled out favors to his own hangers-on, and died of natural causes, a rare distinction on the Palatine.

Lucius’s sons make up the next generation of Vitellii. Aulus, the future emperor, had been part of Tiberius’s entourage in his notorious retirement on Capri. He went to the palace with Caligula, and rose to middling distinction under Claudius and Nero. Nero’s fall brought hard times, but not for long: the new emperor, Galba, saw the mediocre Aulus as a safe commander for the legions in northern Germany. But Galba lost favor with the military. Younger and abler generals saw in Aulus a useful vehicle for their own ambitions. Raised to the purple, he waited at Cologne while their armies marched into Italy.

At Rome, meanwhile, the situation had altered. Galba, “grim and antiquarian in his brutality,” was already dead, having paid the price of his stinginess toward his troops. The Vitellians’ new opponent was the foppish Otho, an associate of Nero’s and the first husband of his second wife, Poppaea. Aulus’s brother, another Lucius, headed north with Otho and his army, as sympathizer, hostage, or both. (The Vitellii were adept at hedging their bets.) The Vitellian forces triumphed, and Otho killed himself. Vitellius arrived in time to tour the battlefield, then headed on to Rome. But already in the East Vespasian, governor of Judaea, was marshaling his legions.

Palatine operates in territory made familiar by Robert Graves’s I, Claudius (1934), a nightmarish world of backstairs gossip, power struggles, poison, and kinky sex. In these elegant hallways, flattery is the real currency: a route to power, a source of safety, sometimes a trapdoor to disfavor or death.

The mentally unstable Caligula needed especially careful handling. A living god himself, he was accustomed to conversing with the Moon goddess. “Can you see her too?” he once asked Lucius Vitellius. Lucius’s reply was well judged: “Only gods can see other gods.” Another courtier was asked casually if he had slept with his own sister, as Caligula was known to have done. Somehow he managed to come up with the right answer: “Not yet.”

In contrast to Beard, Stothard relies mainly on literary sources. Suetonius’s Caesars is one, of course. Another, now less familiar, is Cassius Dio, an early-third-century historian (he wrote in Greek) with access to sources now lost. Perhaps the most important is Tacitus, whose partially preserved Annals and Histories cover most of Stothard’s period. Like the Annals, Palatine opens with the death of Augustus. Stothard appropriates Tacitus’s brooding cynicism and love of innuendo (and not a few of his actual sentences), but his focus is different. Sardonic and outraged by turns, Tacitus gives us the view from the Senate. Stothard concentrates on creatures further down the food chain.

Palatine also makes creative use of a very different text: the versions of Aesop’s fables in Latin verse ascribed to one Phaedrus, who wrote sometime between the later reign of Tiberius (he refers once to Sejanus, clearly already dead) and the late-first-century poet Martial (who mentions him). It has lately become fashionable to see “Phaedrus” as a pseudonym and his fables as coded political utterances. To one scholar Phaedrus is a distinguished Roman barrister. (He seems to know a lot of legal terms.) To another he is a member of the educated elite, exploring “the nature of true freedom in a system where only a few have power.” That he was an imperial freedman (as manuscripts of his poems tell us) and that he wrote as “Phaedrus” because that was his name is a less exciting scenario, though it is the only one supported by evidence.

For Stothard, Phaedrus functions as a shadowy chorus figure and his fables as barbed commentary on the imperial court. In one, the Sun proposes to take a wife. The frogs complain to Jupiter, concerned that the bridegroom will start a family whose combined heat will dry up their pond. “The frogs were the Roman people,” Stothard tells us, “Jupiter was Tiberius and Sejanus the sun.” True or not? Phaedrus, after all, did not invent this fable, which survives in multiple Greek versions. It is in the nature of fables to be applicable to many situations—to events on the Palatine too, if you like—but seeing them as ripped from the headlines in this way seems rash.

“True or not?” is a question Stothard’s readers may often find themselves asking, on small points as well as large. Palatine does not shy away from fictionalization, and the book sometimes feels like one of those cable docudramas in which a portentous voice-over alternates with staged scenes. Here is the younger Publius Vitellius, having a rough day on the German coast:

Indistinguishable from his men, the military standard-bearer for the Vitellii was stumbling through salt ponds that were with every minute less distinguishable from the great grey surrounding sea and sky…. With every cloud of freezing air or fleeing birds came whips of grass like leather, shards of razor shells, goggle-eyed fish, lurid, orange, purple and alive, blood-red parts of what may once have been fish, prawns as clear as water, spiked fins and gills hardened and heading for the few rocks that anyone could see.

The paragraph that follows is lifted nearly verbatim from Tacitus, but this garish bit of prose is all Stothard. If we ask what it is based on, we find only an endnote assuring us that “sea conditions…have changed little in the Channel over 2,000 years.”

In reading the passage it’s hard not to notice the prominence of fish—surely the least of the beleaguered Publius’s concerns that day. Not that the Romans were uninterested in fish. The elder Pliny devoted the ninth book of his huge Natural History to marine animals. A fragmentary ichthyological poem called Halieutica is dubiously ascribed to Ovid. The satirist Juvenal imagined the emperor Domitian and his cabinet solemnly debating what to do about a turbot too large for any available baking dish. Among the most engaging of surviving Roman mosaics are those depicting sea creatures: the fish themselves, in their natural habitat, or their bones and shells scattered on the dining room floor after a banquet.

It is the dining room that provides a clue to what Stothard is up to. Food, for him, is the real key to the early imperial household. Humans need food to live, and to consume food with others is one of our most basic rituals. But in an autocracy all human interactions are corrupted, including this one. Food, like flattery, was one of the languages of power, and the dining room an ideal setting for displays of dominance. A well-timed quip at the imperial table could move a courtier rapidly up the ladder; a misstep there could lead to disfavor or worse. Caligula had a man executed but continued to save him a place at the table: “The empty space had its own meaning.” Domitian served an all-black banquet to a group of terrified senators at which he talked only about death; the place markers were shaped like tombstones, with each guest’s name thoughtfully inscribed.

Dining was a high-stakes game for the emperor, too. Augustus is supposed to have died from eating poisoned figs, Claudius from poisoned mushrooms. Nero’s younger stepbrother Britannicus collapsed and died at a banquet, poisoned by Nero or his agents. The other guests took their cue from the emperor (“just an epileptic fit, nothing to worry about”) and went on eating. Not for nothing does a Pompeian dining table have the image of a skull set into its surface.

It is against this backdrop that Vitellius’s reputation for gluttony—true or not—begins to make sense. To the Romans, the love of food and the hunger for power were one appetite. “You too will get a taste of kingship,” the aged Augustus is supposed to have told the youthful Galba. As emperor, Galba entrusted Vitellius with the German armies because “no men were less to be feared than those who thought only of eating”—one of his many misjudgments. Vitellius’s first banquet as emperor confronted guests with two thousand of the finest fish and seven thousand fowls. His signature dish, the Shield of Minerva, was an image of the empire itself on a vast silver platter: pike livers, pheasant and peacock brains, flamingo tongues, delicacies from every corner of the realm, Parthia to Spain. When all was lost he fled the palace accompanied only by a baker and a cook.

The cleanup was a grim business. The captured Vitellius was paraded through the streets of Rome, prodded under his chin with a sword to make him keep his head up. George Rochegrosse’s 1883 painting of the scene appears on the cover of Palatine, its Vitellius clearly modeled on (what else?) the Grimani head. The emperor whose name suggests a veal calf (vitulus) was tortured to death and his body dragged down to the river on a hook, like a side of meat. On the Palatine the rule was eat or be eaten, and the unfortunate Vitellius had bitten off more than he could chew.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·