wireless is a systematic account of the early development of wireless telegraphy and the inventors who made it possible. Sungook Hong examines several early significant inventions, including Hertzian waves and optics, the galvanometer, transatlantic signaling, Marconi’s secret box, Fleming’s airblast key and double transformation system, Lodge’s syntonic transmitter and receiver, the Edison effect, the thermionic place, and the audion and continuous wave.

Not enough time to read? Try Audible Plus for free!

wireless fills the gap created by Hugh Aitken, who described at length the early development of wireless communication but did not attempt “to probe the substance and context of scientific and engineering practice in the early years of wireless” (p. x). Sungook Hong seeks to fill this gap by offering an exhaustive analysis of the theoretical and experimental engineering and scientific practices of the early days of wireless, examining the borderland between science and technology, depicting the transformation of scientific effects into technology artifacts, and showing how the race for scientific and engineering accomplishments files the politic of the corporate institution. While the author successfully fulfills these goals, the thesis affirms Guglielmo Marconi‘s place as the father of wireless telegraphy.

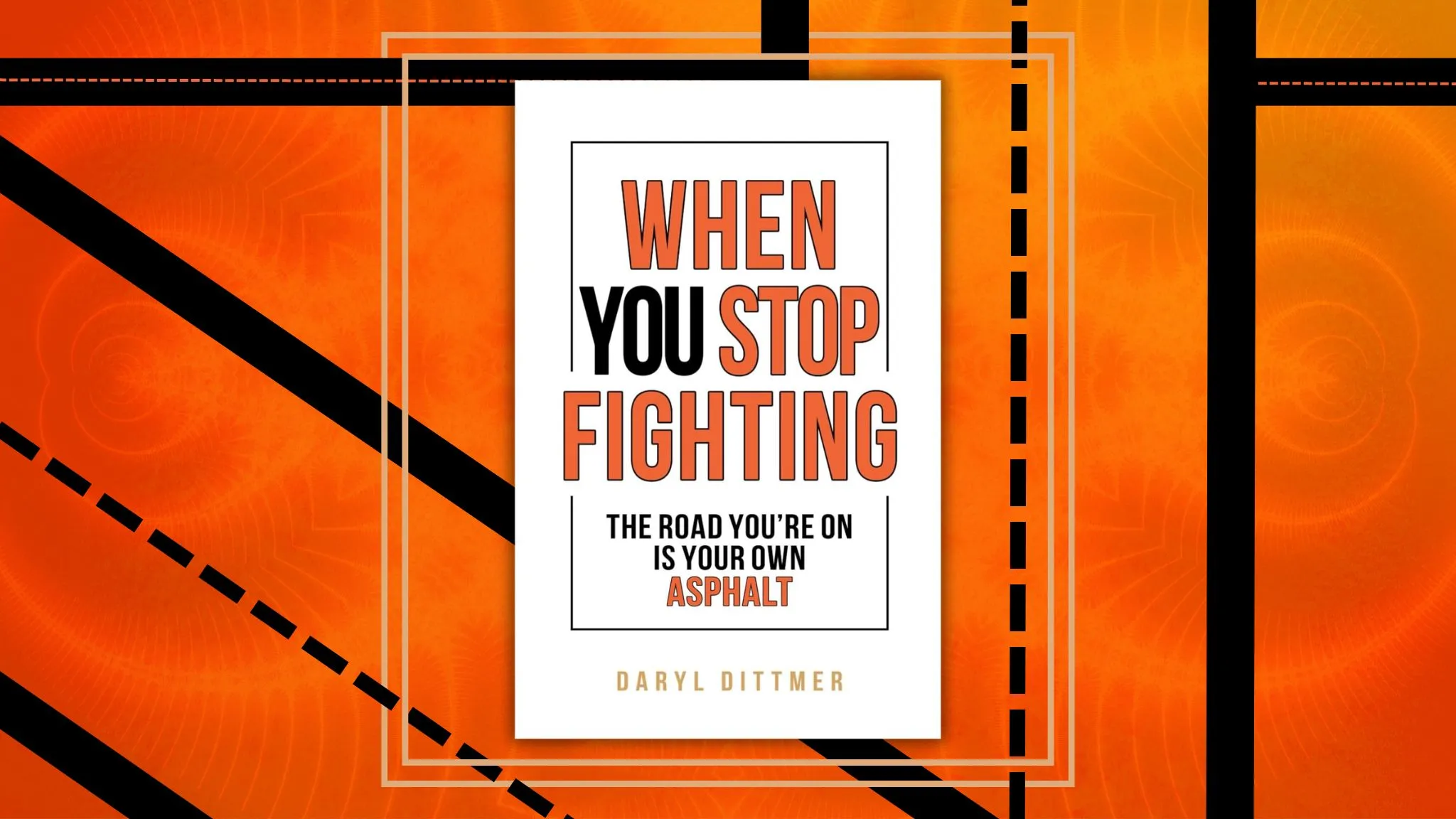

wireless, from Marconi’s black-box to the audion

BY SUNGOOK HONG

MIT Press, January 22, 2010

Nonfiction, Mobile Wireless & Telecommunications

Buy from these retailers:

This post may contain affiliate links, which means I’ll receive a commission if you purchase through my links at no extra cost to you. Please read the full disclosure for more information.

wireless Synopsis

Hong begins with a brief discussion of the 1995 centennial of Marconi’s invention of radio and a rebuttal by the British historians who opposed this claim. Using underused or previously overlooked or perhaps ignored resources, Hong disproves the claims against the originality and ingenuity of Marconi’s 1897 patent on wireless telegraphy. While credit is given to several British scientists and engineers and their scientific discoveries and inventions, it was Marconi, a practitioner, who made the first significant breakthrough in practical wireless telegraphy when he “connected one end of the plate of the receiver, and one end of the transmitter, to the earth” (p. 20).

Marconi transformed these scientific effects into wireless technologies and exploited them commercially. The primary reasons for the dispute surrounding Marconi’s patent are the experimentations, demonstrations, and the feat of British national interests becoming monopolized (particularly by a foreigner). (By 1897, it was clear how wireless telegraphy would impact military interests.) Hong shows in great detail how British scientists and engineers, namely physicists Olive Lodege, J. J. Thomson, Minchin, Rollo Appleyard, and Campbell Swinton, deliberately constructed false science and social claims to discredit the originality of Marconi’s patent. Later, Neville Maskelyne would sabotage a crucial Marconi-Fleming demonstration at the Royal Institution, where Marconi’s purpose was to validate the distance at which messages could travel using wireless telegraphy.

Throughout most of the book, the disharmony between scientific and engineering theory and practice is illustrated in substantial detail. For each invention that contributed to the maturation of wireless telegraphy, Hong describes, at length, the scientist or inventor, the conceptions and context for discovery, the demonstration of its scientific or technical worth, the transformation of specific scientific discoveries into technological artifacts or the contribution of technology to science, as in the case of the Edison effect and thermionic emission. Regardless of the scientist or inventor and the original context of invention, Marconi continued to hone and exploit these technologies in his quest to perfect wireless telegraphy. Marconi transformed Fleming’s invention, the thermionic valve–into a “sensitive detector for wireless technology” (p. 148), an example of one of many cases where Marconi’s ingenuity and insight proved resourceful.

In the final chapter, Hong introduces the technologies that eventually led to the making of the radio age, namely the audion and the continuous wave. Unlike the early discoveries and inventions of wireless telegraphy, the audio revolution was an example of “simultaneous innovation” where “at least four engineers, and perhaps six, arrived at the amplifying and oscillating audion circuits almost simultaneously” (p. 158). These simultaneous discoveries would eventually lead to multiple first claims and patents, lawsuits by both individuals and corporate interests, the reversals of patents, and intense public debate. The controversy that once focused on Marconi and his exploration of invention became common practice in highly technical and scientific fields.

wireless Book Review

Overall, the book is exceptionally well organized and researched. Hong does a superb job of illustrating how science and engineering discovery, invention, and demonstration shape an institution and, in turn, how an institution exploits science and technology for commercial purposes. More importantly, though, the author validates the originality and ingenuity of Marconi’s 1897 patent by discrediting those scientists and engineers who used their credibility to mislead the public. For those readers interested in discovering the origins of wireless telegraphy, along with the pioneers, the science, and the engineering inventions that made it all possible, wireless is a great place to start.

Looking for more book reviews?

Search the She Reads Everything archives!

English (US) ·

English (US) ·