Jeffrey Davies is a professional introvert and writer with imposter syndrome whose work spans the worlds of pop culture, books, music, feminism, and mental health. In addition to Book Riot, his writing has appeared on HuffPost, CBC Arts, Collider, Slant Magazine, PopMatters, and other places. Find him on his website and follow him on Instagram, Threads, or Bluesky.

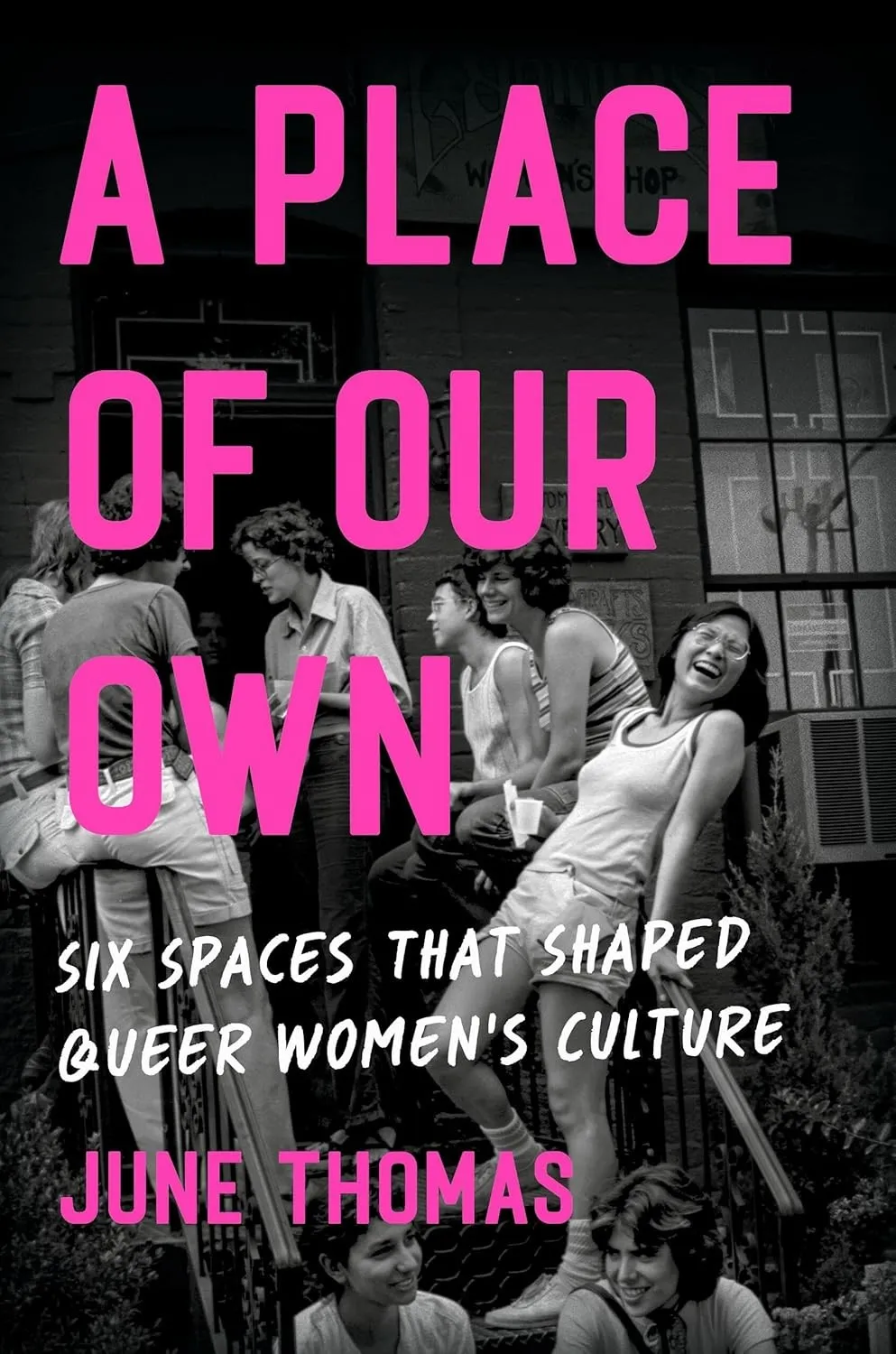

Despite its unconventional operation in its earliest days, its existence was a monumental step forward during second-wave feminism. “[I]t was hugely important as a central location where women could find books about feminism, along with periodicals chronicling the growing women’s liberation movement,” wrote June Thomas in A Place of Our Own. One original customer remembered the Brown House commune as the “center of the countercultural scene, the place you called when you wanted to know what was going on in the Twin Cities.” It wasn’t something you could find in the phone book. “You had to be somewhat connected,” recalled Cheri Register. “You could find it in the alternative presses.”

Unlike many pioneers of second-wave feminism who rejected intersectionality, Amazon Bookstore was now dedicated to being a safe place for all women.

Book Deals

Sign up for our Book Deals newsletter and get up to 80% off books you actually want to read.

The original owners of Amazon Bookstore didn’t remain in the game for very long. Two years after opening it, Richter and Morse left Brown House to start a karate school for women only in hopes of teaching more self-defense to the female population. Their own story ended badly when Morse experienced a change in political ideology, later marrying a Republican state representative staunchly opposed to gay rights and abortion, and eventually becoming an avid supporter of Donald Trump herself.

As a result, Richter and Morse sold Amazon Bookstore’s remaining inventory to Karen Browne and Cindy Hanson for $400 ($3,100 in 2025). Although the bookstore continued its habit of existing in the homes of its owners, its new location on Cedar Avenue South in Minneapolis became a bit more store-like, with Browne and Hanson adding a giant sign to the second floor of their home, reading, “Amazon Book Store. Feminist Literature.” After adding more opening hours to the business as well as more advertising, Amazon Bookstore was now open four days a week, including evenings and weekends. Just six months later, its location changed again.

Now housed in the Lesbian Resource Center in the Wedge neighborhood of South Minneapolis, Amazon Bookstore was returning to its roots. But women who were going to the Lesbian Resource Center were likely driven there for other interests besides browsing books. “The building was also home to a theater troupe, a softball team, and a literary magazine, and it served as a venue for rap groups and coffeehouses,” wrote Thomas. “The books were almost an afterthought, just a few boxes in the center’s basement … At this point, Amazon was a labor of love. The owners were volunteering their time and energies, not trying to turn a profit.”

Its owners knew that Amazon Bookstore needed a storefront if it was going to survive. In September 1973, the bookstore moved to its own physical location for the first time on West Lake Street, where they were now open six days a week. They had something of an open-door policy for women and valued their input on how the business should continue to be shaped and grown. A year later, in October 1974, Amazon Bookstore would move one more time to Hennepin Avenue, where it would remain for the next decade.

Unlike many pioneers of second-wave feminism who rejected intersectionality, Amazon Bookstore was now dedicated to being a safe place for all women. Diane Como, a longtime Amazon employee, remembered the Hennepin Avenue location well. “We had a lending library where you could sit and read, sit and watch women, sit and look around, get to know people, ask questions,” she said. “It was safe, and that made us different.” Safety continues to play a huge role in women’s spaces in the 21st century, and despite being a rather novel subject in the 1970s, Amazon Bookstore understood its assignment as a queer feminist bookstore. Long before the digital age of chat rooms and social media, marginalized people’s only choice in meeting and interacting with other people like them was in public. Feminist bookstores became a central breeding ground for this type of inclusive community.

“Customers trusted advice from the women of Amazon because they read the books on their shelves and they were experts on the companies that produced them,” Thomas wrote. Writer Ellen Hart remembered going into the Hennepin Avenue location for the first time during a transitional period in her life, looking for books on lesbianism and sexuality, which she wasn’t finding in mainstream bookstores. She recalled the bookstore as being “very warm and very friendly,” offering an elite inventory and playing music she had never heard before. Though these types of first encounters for queer people still exist now, they were much more vital in the years before the Internet. After moving to a storefront and growing the business, however, Amazon Bookstore resisted the label of “lesbian bookstore” in an attempt to maintain its promotion as a space for all women.

By 1985, Amazon moved for a sixth time to a new location in Minneapolis’ Loring Park neighborhood. Its latest location was described as “more spacious and attractive,” and in an age that predated widespread gentrification and rent hikes, Amazon Bookstore continued to flourish, though it wouldn’t be able to avoid being labeled a lesbian bookstore for long after it became neighbors with Ruby’s Café, a popular lesbian hangout in the ‘90s. As café owner Mary Baheman recalled in 2020, “You could see who went home with who from the lesbian bars because of who came in for breakfast together. It was the place to go on Sunday to see what happened on Saturday.” And as any book lover knows, the best thing to do after brunch is to continue gossiping over a little light book shopping next door.

The 1990s also brought with it the rise of big box and chain stores. Barnes & Noble and Borders were now offering some of the same stock offered by Amazon Bookstore for discounted prices. (See also: the entire plot of You’ve Got Mail.) But Amazon held steady, even when Borders moved in on another local independent bookstore. Its management maintained that superstores “[didn’t] seem to be pulling customers” from them, but by 1995, they started to admit that even the loss of a small amount of customers was detrimental to a small business like Amazon Bookstore.

Another storm was brewing in 1995 as Amazon Bookstore celebrated its 25th anniversary. Across the country in Seattle, another business that sold books was launching. Much like Amazon Bookstore when it first started out, this new business didn’t have a storefront. It had something that the pre-digital era had yet to fully comprehend: the ease and convenience of shopping from your own home. The age of Amazon.com had started, and although it didn’t immediately damage the existing Amazon, it would be a slow descent into trouble.

As Amazon.com found its bearings, Amazon Bookstore continued to thrive. Annual sales had reached a high of $600,000 ($1.3 million in 2025). At the time, an employee told the Minnesota Women’s Press that they attributed the store’s success to “a friendly and creative staff, community outreach work, the burgeoning of restaurants on our block, and most of all, our loyal community who continue to understand the importance of supporting a feminist bookstore.”

For how long, though? The Loring Park neighborhood was starting to gentrify with the addition of chain businesses like Starbucks, which started increasing traffic and parking issues. Amazon Bookstore did what it has always done: it turned to its community for support. They started hosting more author events, open mic nights, and classes for women learning English as a second language. They started selling course textbooks for the University of Minnesota. They continued to collaborate with Ruby’s Café. They had sales, parties, and continued to sell books. But would it be enough?

Sadly not. The years 1995 and 1996 began showing consistent declines in sales. By the end of the decade, the bookstore that was always so vibrant and talkative had now become quiet and still. Amazon Bookstore wasn’t alone in losing steady streams of customers to online shopping at the end of the ‘90s and into the early 2000s, but the store was learning that there wasn’t exactly safety in numbers anymore. And just when it seemed like things couldn’t get any worse, the store that now shared a name with an online shopping service that booksellers hoped was just a novelty was experiencing a unique identity crisis.

Soon after Amazon.com launched, Amazon Bookstore noted a sharp increase in phone traffic with online customers confusing the beloved, longtime feminist bookstore for the online shopping site. What was even worse was that Amazon Bookstore customers began placing orders from Amazon.com, believing they were purchasing books from their favorite feminist indie. Amazon Bookstore manager Barb Wieser told the Corporate Legal Times that, during the 1998 holiday season, the store was receiving up to 20 calls a day that confused them with Amazon.com. “They were looking for books we didn’t have. They wanted to come down and get them. We fielded so many calls it felt like we were working for Amazon.com,” she said.

In April 1999, Amazon Bookstore sued Amazon.com, claiming it was “losing the value of its trademark, its product and corporate identity, its ability to move into new markets, and control the goodwill and reputation it has developed over the last 30 years.” Of course, Amazon.com contested the lawsuit, and did so underhandedly. The online business’s lawyers asked Amazon Bookstore employees during depositions if they had promoted “lesbian ideals in the community” and if they themselves were gay, both questions the women rightly refused to answer. Although they argued they were trying to establish that Amazon.com was interested in selling all kinds of books and Amazon Bookstore was only interested in selling feminist literature, their line of questioning suggests that Amazon.com’s lawyers were not afraid to resort to homophobia to win their case.

They settled out of court, and Amazon Bookstore agreed to rebrand itself as Amazon Bookstore Cooperative in order to distinguish itself from the online store of the same name. At the dawn of the new millennium, the bookstore moved for a seventh time after parking and gentrification in the Loring Park area continued to get worse. Although it was now in an even more spacious location on the ground floor of the Chrysalis Women’s Center in Minneapolis, the already-struggling store was adding on more complications by promoting a change of address. There was worry that old customers wouldn’t seek out their new location.

According to A Place of Our Own, “Between the chains and online competition, it became harder and harder for any independent bookstore to survive the 2000s.” The Cooperative lamented that they would have to close the bookstore in 2002 after they saw a 15% drop in sales following 9/11, but the community rallied as best it could to save the store, at least for a little while longer, by bringing in $30,000 through a fundraising campaign. Although finances remained tight, Wieser told Publishers Weekly in 2003 that she was “more hopeful than before” that the Cooperative would stay open.

“It would be wrong to think of Amazon — or other feminist bookstores — as having failed because their owners made poor choices. The economics of bookselling are daunting for anyone brave, or foolish, enough to go into the business.” — June Thomas

And it did, for five more years, an impressive feat in the difficult economic climate that marked the decade. In June 2008, the Amazon Bookstore Cooperative announced that it was closing its doors. Wieser, who had worked at the bookstore for 21 years, told MinnPost that “bookstores are owned by people with money” and that “young people don’t see a future in it.” But 2008 ultimately wouldn’t be the end of Amazon Bookstore. Just before closing for good, lesbian bookworm Ruta Skujins bought the store with IRA funds. A change in ownership required a change in name, according to the settlement with Amazon.com, so the Amazon Bookstore Cooperative became True Colors. Despite surviving for four more years until 2012, it was a colossal failure, with Skujins telling the Pioneer Press that she had put all of her retirement savings, a quarter of a million dollars, into the store and now had to recoup the $100,000 she owed to bill collectors once the business failed.

“It would be wrong to think of Amazon — or other feminist bookstores — as having failed because their owners made poor choices,” wrote Thomas. “The economics of bookselling are daunting for anyone brave, or foolish, enough to go into the business.” Indeed, economics shift from era to era, generation to generation. What was once a necessary queer feminist space for the marginalized to find themselves both recognized in literature and among like-minded people merely became overrun by the ravages of time and the Internet. In the post-pandemic era, when indie bookstores have enjoyed something of a renaissance, it’s important to look back at the beloved local indies, especially those catering to diverse communities of any kind, that brought us to where we are now.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·