In 2019 Alex Stamos, the former chief of information security at Facebook, founded the Stanford Internet Observatory, a research center focused on foreign influence operations and other abuses of social media. Stamos had left Facebook in frustration over its failure to disclose more to the public about Russian interference in the 2016 US presidential election. He hired Renée DiResta, an expert on the viral spread of mis- and disinformation, as head of research for the new organization.

DiResta led the observatory’s studies of topics including child sexual abuse and Russian propaganda. In 2020 she and the institute launched a project called the Election Integrity Partnership to expose attempts to suppress voting or baselessly delegitimize election results. Its method was to send virtual “tickets” flagging potential disinformation campaigns to the social media platforms hosting them—principally Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. In about a third of the cases, the platforms took action, either attaching warning labels or, more rarely, removing posts or taking steps to limit their reach.

After Joe Biden’s victory, the Election Integrity Partnership’s efforts to counter viral manipulation became an obsession of the MAGA right. As DiResta recounts in Invisible Rulers, the attacks against her started with an election denier named Michael Benz, who had worked in Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson’s speechwriting office before serving for three months in a low-level position in Donald Trump’s State Department. Styling himself a cybersecurity expert and free speech advocate, Benz alleged that the Election Integrity Partnership was a “social media censorship bureau” targeting the right and said that DiResta was wielding an “AI censorship death star superweapon.” (Online, Benz also had an alt-right identity, “Frame Game,” which he hid behind to raise the alarm about “white genocide” and to discuss Hitler’s good points.) According to Benz’s conspiracy theory, the Biden administration was utilizing the Election Integrity Partnership to prevent conservatives from using Twitter and other platforms to warn of fraud in the upcoming 2024 election. It was, as Benz put it with his usual understatement, “a scale of censorship the world has never experienced before.”

DiResta and her colleagues first tried ignoring these ludicrous claims, then refuted them point by point, neither of which helped. She did not immediately recognize that she was being made into what she calls a “main character” in an upside-down viral narrative. Podcasts hosted by Steve Bannon, Sebastian Gorka, and John Solomon echoed Benz’s charges. Right-wing Web publications amplified them; a story that appeared on multiple sketchy sites called the Stanford Internet Observatory a “digital reboot of the CIA’s psychedelic mind-control experiments.” Jack Posobiec, of Pizzagate fame, tweeted to his 1.8 million followers the false allegation that DiResta and a colleague were “behind censoring the Hunter Biden laptop.”

Violent threats and harassment deluged DiResta’s social media accounts. The situation got worse after Elon Musk bought Twitter in 2022 and enlisted journalists including Matt Taibbi and Bari Weiss to publicize a set of internal documents known as the Twitter Files. Taibbi and the freelance policy advocate Michael Shellenberger amplified the false charges that DiResta had censored 22 million tweets and was concealing her ties to the CIA. (She made no secret of having been a college intern there twenty years earlier.) Jim Jordan, the powerful Ohio congressman and 2020 election denier, invited Taibbi and Shellenberger to testify about their “findings” before the House Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government.

In pursuit of this investigation, Jordan demanded that employees of the Election Integrity Partnership and the Stanford Internet Observatory turn over their e-mails dating back to 2015; the request became a subpoena. His staff demanded “voluntary” interviews with former student interns. Those who submitted were grilled for hours. Incriminating quotes, taken out of context, were then leaked to the same MAGA press outlets that were driving the story. Another conspiracy-minded Republican, Representative Dan Bishop of North Carolina, issued parallel demands on behalf of the House Homeland Security Committee.

Next came the lawfare. Stephen Miller, the former White House senior adviser who would return as deputy chief of staff, brought a class action suit against DiResta, Stamos, Stanford, and other organizations through his America First Legal Foundation. He filed the case in a federal courthouse in Louisiana (where the only active judge was a Trump appointee) on behalf of Jill Hines, a director of Health Freedom Louisiana, an antivaccine organization, and Jim Hoft, the founder of The Gateway Pundit, a far-right news site, claiming that DiResta and others had colluded with tech platforms to deprive the plaintiffs of their civil rights by acting as de facto agents of the federal government and suppressing their free speech.

It is challenging to unpick this Orwellian skein, which may be why the episode has been underreported. But seen from the perspective of 2025, DiResta, the Election Integrity Project, and the Stanford Internet Observatory were canaries in the coal mine for the many-pronged assaults on universities and other institutions that have become hallmarks of the second Trump administration.1 Attempts to expose Russian disinformation were themselves denounced as disinformation—part of the “Russia hoax.” Viral propaganda tools were deployed against those attempting to limit the reach of viral propaganda tools. Cries of censorship were used to silence opponents, curtail research, and stop fact-checking. Investigating the weaponization of the government meant weaponizing the government.

A crucial lesson that might have been learned sooner was that institutions must forcefully fight back against this kind of bullying. What ultimately doomed the observatory was not that right-wing conspiracists attacked it but that its parent institution, Stanford, failed to defend it, responding to media inquiries with “no comment.” The university, it seems, was largely concerned with limiting its legal costs and not inflaming the situation further. Its strategy was to keep a low profile and mollify the attackers. DiResta’s contract was not renewed, and others were told to look for work elsewhere. Last year Stanford shuttered the observatory, continuing only its work on child safety, and under a different banner. According to its no-longer-extant website, the Election Integrity Partnership “finished its work after the 2022 election and will not be working on the 2024 or future elections.” But Miller’s lawsuit against DiResta and her defunct project is ongoing.

How did we get to this place, where mirror realities have replaced shared facts? The answer has something to do with the use of algorithms to personalize social media feeds. The concept of an algorithm as a set of instructions for solving an algebraic equation goes back to Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, a ninth-century Persian mathematician. (The term algorithm derives from a Latinization of his name.) The colloquial usage to mean a personalized recommendation engine is quite recent. Amazon began using an algorithmic technique known as collaborative filtering in the late 1990s to suggest products based on purchases by users with similar proclivities. Recommendation algorithms were the secret recipes behind services like Spotify and Netflix, the formulas that made them addictive and fueled their exponential growth. To DiResta, algorithms and the people who are able to manipulate them most effectively are our new “invisible rulers.” She borrows the phrase from Edward Bernays, the father of public relations, who used it in his 1928 book Propaganda to describe the hidden shapers of public opinion.

In the early years of social media, algorithms were often seen in a positive light. Barack Obama’s first term, coinciding with the Arab Spring, was a hopeful time for the antiauthoritarian potential of Facebook and its quirkier cousin Twitter. But as the revolution fizzled in Tahrir Square, some of the early idealists began raising concerns about the possibility that these platforms could become forces of propaganda and polarization. In 2011 Eli Pariser, the executive director of MoveOn.org, warned of what was coming in a book called The Filter Bubble, predicting a balkanizing information landscape in which conservatives would get conservative news and liberals liberal news.

It was an accurate prophecy. That same year Facebook replaced its reverse chronological “newsfeed” with an algorithm that prioritized posts based on interactions, past behavior, and time spent. Twitter and YouTube soon followed suit in adopting algorithmic, as opposed to chronological or search-based, curation. The algorithmic evolution of these platforms heightened their potential for harm. As DiResta astutely observes, “At its worst, Twitter made mobs—and Facebook grew cults.” One of those cults was the right-wing conspiracy group QAnon, which matured on Facebook into a violent subculture.

Filter bubbles meant that people who were more engaged with mainstream media seldom saw the dank memes launched by troll factories like Russia’s Internet Research Agency. And most people weren’t aware until after the 2016 election that Facebook itself had helped the Trump campaign microtarget incendiary messages and fundraising appeals.2 After the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which exposed the company’s unauthorized release of user data for political advertising, social media platforms went through a period of soul-searching about their function as global conduits for antidemocratic disinformation.

Facebook’s new policy, DiResta writes, was to “remove, reduce, and inform.” “Remove” meant blocking foreign election interference. “Reduce” meant overriding the platform’s newsfeed algorithm to demote or “throttle” undesirable content. “Inform” meant attaching a pop-up notice about fact-checking on posts that contained disputed information. All the leading platforms were now on the lookout for “coordinated inauthentic behavior”—bots in St. Petersburg impersonating moms in Tennessee, say. Ahead of the 2020 election Mark Zuckerberg took the suggestion of the Harvard law professor Noah Feldman and created an independent oversight board with the power to override Facebook’s decisions about removing content.

The bad conscience of social media companies also played itself out during the Covid-19 pandemic. They did not want to be used to spread deadly misinformation about the disease and vaccines. In some cases they were too zealous in overriding their algorithms to ban or downgrade advocacy of the lab leak hypothesis or skepticism about mask mandates and school closings. Twitter had long described itself as “the free speech wing of the free speech party.” But under the distracted leadership of its cofounder Jack Dorsey, it joined Facebook in blocking reporting on the contents of Hunter Biden’s abandoned laptop, suspecting a Russian hoax in the days before the election. (The laptop’s contents were subsequently shown to be genuine.)

After the January 6 insurrection, nearly all the tech giants deplatformed Trump or instituted content restrictions targeted at his most extreme supporters. Facebook and Instagram suspended him from posting.3 Twitter “permanently” banned him. Snapchat disabled his account. YouTube took down a video posted by Trump and stepped up its enforcement around election disinformation. Apple and Google blocked Parler, a social media platform that did not moderate content, from their app stores. TikTok and Pinterest suppressed certain hashtags. Shopify took down Trump’s campaign store. Stripe refused to process donations to Trump’s campaign.

That same month, in a decision that restored a deleted post advocating hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for Covid-19, the Facebook Oversight Board noted that “a patchwork of policies found on different parts of Facebook’s website make it difficult for users to understand what content is prohibited.” This wasn’t an accident. The company preferred to improvise its rules in response to both commercial and political pressures. But without principled commitments to anything other than user growth, Facebook and other platforms made themselves easy marks for those on the right who were adept at relentlessly working the refs. Algorithmic opacity fueled their claims of “shadow banning.” Even attempts to create more clarity and consistency were denounced as expressions of bias. Missouri senator Josh Hawley called the Facebook Oversight Board a “special censorship committee.”

In 2021 Trump sued Twitter and Facebook for blocking him. According to The Wall Street Journal, at a Mar-a-Lago dinner after Trump won the 2024 election, Zuckerberg was told that he would have to resolve the lawsuit to be “brought into the tent.” Zuckerberg wrote a check for $25 million, agreed to end his company’s fact-checking program, made the Republican political operative Joel Kaplan his chief of global affairs, and appointed Trump’s friend Dana White, the president of the Ultimate Fighting Championship, to his board of directors. Perhaps as a result of his $288 million in contributions to Trump’s 2024 campaign, Musk got off more cheaply: his settlement bill was only $10 million.

In MAGA world, social media is judged by a simple standard: Cui bono? When he thought that TikTok was a tool the Chinese government might use against him, Trump supported banning it on national security grounds. After coming to believe that the platform helped him more than it helped the Democrats, he simply ignored the law Congress passed requiring TikTok to cease operating in the United States under Chinese ownership. If algorithmic rules help the left, they’re censorship. If they advance the right, they’re upholding free speech.

Twitter’s biggest problem in the era before Musk bought it was harassment and abuse, which inhibited user growth and limited the platform’s appeal for advertisers. But judging by his compulsive output of tweets and retweets, Musk was absorbing a different perspective inside his own filter bubble. His left-libertarian views were shifting to the right in apparent response to the adulation he was receiving from a variety of fringe figures who shared his love of juvenile jokes and memes. All of them were obsessed with the inconsistency of Twitter’s moderation policies. The complaint that led Musk to spend $44 billion to acquire the company was that it was suppressing antiwoke speech.

Musk’s almost accidental acquisition of Twitter and his concurrent shift to the right are colorfully recounted in Character Limit by the New York Times reporters Kate Conger and Ryan Mac. It is a well-reported if at times overly detailed account that, like DiResta’s book, gives us a retrospective preview of what was in store after Trump’s 2024 victory. Just as he later did to the US government at DOGE, Musk treated Twitter as a reverse start-up. Proclaiming his contempt for the waste and incompetence that preceded him, he moved quickly to change the platform’s name to X, eliminate content moderation, fire more than half of the company’s staff, and demand oaths of loyalty and proof of productivity from those who remained.

Shortly after the deal closed in October 2022, Musk sent a 3:00 AM memo to the entire staff entitled “A Fork in the Road.” “If you are sure that you want to be part of the new Twitter, please click yes on the link below,” he wrote. “Anyone who has not done so by 5pm ET tomorrow (Thursday) will receive three months of severance.” Within days of the 2024 presidential inauguration, Musk got the Office of Personnel Management to deliver a memo with the same title to two million federal employees. “You may wish to depart the federal government on terms that provide you with sufficient time and economic security to plan for your future—and have a nice vacation,” it read. Employees were encouraged to simply reply, “Resign.” To objections that he was breaking laws and labor agreements, Musk offered the same answer: sue me.

Musk’s behavior seemed almost intended to destroy value at the company he had just acquired. No one on Twitter’s attenuated senior team could talk him out of selling blue verification badges, with the predictable consequence that impostor and parody accounts were able to appear authentic. At all hours Musk endorsed messages from conspiracy theorists, white nationalists, and antisemites. When the Anti-Defamation League criticized him, he whipped up an online mob and threatened to sue the organization for harming his ad business. When advertisers threatened to pull back their spending because of the controversy and chaos, he told them at a conference to “go fuck” themselves.

Musk was probably right to restore a number of accounts that Twitter had overzealously suspended. But he was soon blocking content more arbitrarily than the previous regime had, with a more personal set of motives. Not long after gaining control, he began suspending the accounts of journalists who reported on disputes at the company and of critics who got on his nerves, such as Paul Graham, the cofounder of the start-up incubator Y Combinator.

When a Biden tweet about the 2023 Super Bowl got more views than a Musk tweet on the same subject, Musk demanded that product engineers find the cause, asserting that it must be “incompetence or sabotage.” Engineers improvised a fix, introducing the code “author_is_elon,” which gave the owner’s posts priority over everyone else’s. If you’re on X these days, you’ve probably noticed that Musk’s posts have a tendency to rise to the top of your feed, whether you follow him or not. This is algorithmic personalization, built around the publisher rather than the user.

At Musk’s X, there is no longer much pretense that politically neutral rules determine what users see. The platform now practices what DiResta calls “preferential dissemination.” More recently, the Times investigated the mysterious collapse of the reach of several prominent Trump supporters, from hundreds of thousands of daily views to in some cases just a few thousand, after they challenged Musk about immigration policy.4 That these were far-right voices only underscores the point: X is now the kingdom of Musk, and anyone else posts at his pleasure. Instead of optimizing for growth and revenue, the way Facebook does, he optimizes the site for his ever-changing moods. Musk has done what Zuckerberg at his worst has never done: seized his megaphone for a monologue.

The algorithm has become, in Marshall McLuhan’s terms, the dominant medium of the digital age. The way it selects, curates, and presents information shapes our perspectives on the world in ways comparable to earlier information technologies like the printing press, radio, and television. Kyle Chayka, a staff writer at The New Yorker, sees this transformation as negative, but his concern isn’t that algorithms are isolating us in separate bubbles. The problem , as he sees it, is the opposite: they’re breeding homogeneity in taste, subjecting us all to an increasingly insipid wallpaper culture.

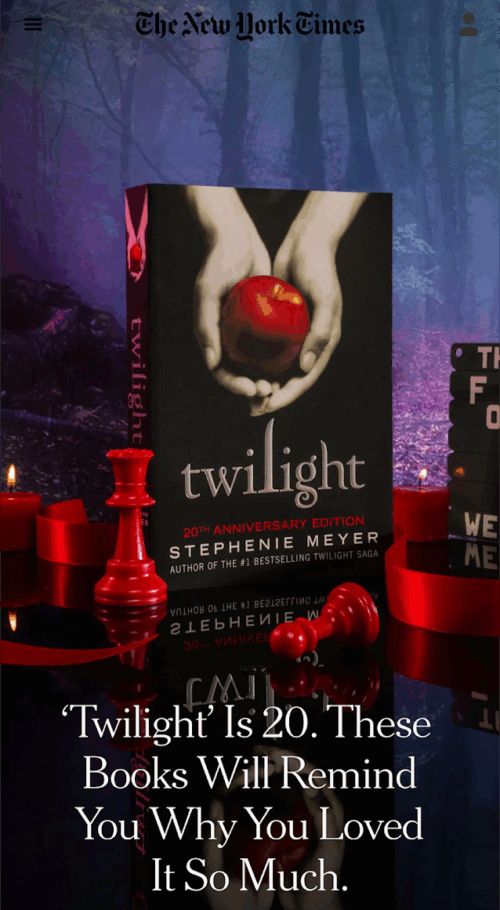

An illustration of this is what he describes as the generic hipster coffee shop. It was in such places that Chayka wrote much of his first book, The Longing for Less (2020), about the minimalism trend. A Yelp search can point you to one of these establishments in any large city on the planet. You’ll recognize it by the industrial wooden tables, subway tiles, latte art, and good Wi-Fi. “These cafés had all adopted similar aesthetics and offered similar menus, but they hadn’t been forced to do so by a corporate parent, the way a chain like Starbucks replicated itself,” he writes. “Instead, despite their vast geographical separation and total independence from each other, the cafés had all drifted toward the same end points.” The agreeable culprit behind this convergence is the algorithm, especially as coded by Instagram and TikTok, which he blames for everything that’s, well, a little basic, from avocado toast to Bridgerton to the novels celebrated on #BookTok.

Driving this convergence are the people he calls “algorists”—a less loaded synonym for “invisible rulers.” Though Chayka doesn’t introduce us to any of them, the term is helpful because of the way it reminds us that recommendation algorithms are products of corporate choices and strategies, not indelible features of the natural landscape. The banal aesthetic we’re marinating in is the outcome of a discipline that engineers at Meta, Facebook’s parent company, call “growth hacking.” It flows from the relentless pursuit of user engagement metrics: daily active users, average session length, feature retention rate, funnel completion rate, and so on.

Some of Chayka’s observations resonate. Others are either too nebulous or incongruously particular. Netflix-produced dramas, he says, are enjoyable but not memorable. He finds its Instagram-inspired food shows to be “placid, undisruptive, and ambient—developing the audiovisual equivalent of perfect linen bedsheets.” His experience with music is less intense than it used to be, he grumbles, because he no longer spends a lot of money on CDs.

When he writes about literature, Chayka can sound a bit like a hipster coffee shop himself. Autofiction by Karl Ove Knausgaard, Rachel Cusk, and Sally Rooney, he gripes, presents a “vicarious, almost consumerist view of the life of a successful writer” for “their cultural-elite target audience.” Their novels “have come to resemble or glorify the social platforms themselves—all the better to be distributed through them.” Knausgaard finished writing the final volume of My Struggle shortly after Instagram was founded in late 2010, so I’m not sure how fair it is to accuse him of pandering to it. In any case, there is something grating about this accusation of commercialism, which echoes Dwight Macdonald’s complaints about middlebrow culture impersonating high art—without Macdonald’s élan.

There must be more interesting things to notice about the effects of algorithms on culture, which are everywhere around us. Instagram turned photography square. Spotify and TikTok have driven a reduction in the typical length of songs from more than four minutes in the 1990s to just over three; the average length of a song that appears on Spotify’s charts has fallen thirty seconds since 2019 and dropped by fifteen seconds between 2023 and 2024 alone. As a result, songs are different: fewer have bridges, and the chorus often comes sooner than it used to. Netflix turned documentary films into popular entertainment, but they no longer have a point of view.

And surely the cultural consequences of algorithms aren’t entirely negative. Even as they amplify the hits, recommendation engines also do with cultural interests some version of what they do with political ones: connect people around various minority tastes. When the taste isn’t for QAnon fantasies, I don’t see the harm. If you love Wes Anderson, photojournalism, ceramics, or most any other category of physical or visual expression, social media has the capacity to intensify and deepen your relationship by connecting you with a virtual community that shares your enthusiasm. Sustaining artistic interests that lie outside of mainstream culture is the opposite of flattening.

Chayka doesn’t spare much concern for the cultural consequence that seems to me the most harmful: what algorithms are doing to attention spans and the ability to sustain focus. These days all of us fight the attraction of distraction. The very presence of Facebook, X, Instagram, TikTok, Spotify, and YouTube in pockets makes reading a book or immersing oneself in artistic experience more challenging. Then again, if Chayka got through all 3,600 pages of My Struggle, brain rot may not affect him.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·