Here is a news report that absolutely dropped my jaw: the Tribal Alliance Against Frauds (TAAF) has released a report that debut romance author Colby Wilkens, whose bio says she is of Choctaw and Cherokee descent, has no Native ancestry.

The TAAF “is an intertribal anti-fraud non-profit whistleblower organization comprised of allies and citizens of Tribes whose sovereignty has been formally acknowledged.”

Wilkens is the author of If I Stopped Haunting You, which released last week on October 15, 2024. Our guest reviewer, Lisa, struggled with the book, and gave it a D-.

Per the report, Wilkens claimed an Indigenous ancestor named Jack Alford Adams, whose father was named William Henry Adams.

William Henry Adams’ name appears on the Dawes Roll, which lists people who were “accepted as eligible for tribal membership as a Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, or Seminole native” in 1898.

However, it turns out that there are, or were, two William Henry Adams.

Wilkens, per the TAAF report, is descended from “the non-Indigenous William Henry Adams.”

We looked at Jack Alford Adams’ father, William Henry Adams (1861-1917), and found someone of the same name on the 1898 Cherokee Dawes Roll, but it is a different person.

The William Henry Adams registered on the Dawes Roll (number 4276) was 9 years old in 1898 and had different parents. Though they had the same name, they were different people.

This is a common challenge for Pretendians.

A few things jump out at me from the TAAF report. First, this research is thorough. TAAF traced Wilkens’ ancestry back TEN generations.

Second, Lianna Costantino, co-founder and director of TAAF, told reporters Alex Turner-Cohen and Isabel Vincent at Page Six that “There were multiple complaints about this person. Lots of people had suspected for some time.”

“Multiple complaints.”

In addition, Cohen and Vincent reported that:

Several years ago, David Cornsilk, a professional genealogist and managing editor of the Cherokee Observer, commented on a Facebook post Wilkens made about her alleged Cherokee and Choctaw ancestry.

“Since you are making money marketing your writing as a Native American it seems you would want to find out for sure,” Cornsilk wrote.

“I would like to invite you to join our free research group and our team of genealogists and historians will find out the truth for you.

“You owe honesty and transparency to your readers, I hope you will take the high road in this matter.”

If Cornsilk commented several years ago, and TAAF received “multiple complaints,” this report and its findings may not have come out of nowhere.

The issue, in addition to claiming heritage that isn’t true or verified, is marketing and profiting from a false Indigenous heritage.

According to Costantino, TAAF tries to help people save face if they’ve made a mistake with their geneology. She says it is common for people to get caught up in a “family myth” passed down through generations about having native heritage, which few then go on to check.

But she explains people have a responsibility to do so, especially if they make it part of their “whole personality” or use their heritage as part of their career.

So once a person starts to profit from claims if Indigenous heritage or identity, they should absolutely know without a doubt that these claims are true.

In their report TAAF explains “why this matters,” why it’s so important to verify claims of Indigenous heritage:

Why this matters: Fewer than 2.5% of children’s and Young Adult books were published by or about Native peoples in 2023, according to the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. This means that any books representing Native Americans have an outsize influence on how others view Native peoples.

This is especially the case for books published by major publishers with the promotion these books will likely have. This drowns out attention to genuine Native voices who are already working hard to counter centuries of oppression and misrepresentation.

TAAF also states that they “call on book stores and events organizers not to support this book.”

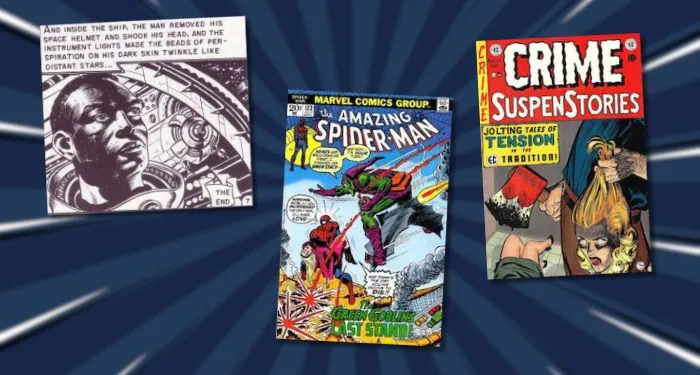

The most absurd part for me: If I Stopped Haunting You is about two Indigenous authors who get into an argument on a panel at a book con about Indigenous representation IN PUBLISHING.

I…cannot think of what to say that fully explain my bewilderment here.

From the review:

Penelope “Pen” Skinner is looking to improve her sales by appearing at Book Con. Unfortunately, her most hated enemy — rival author and former hero of hers Neil Storm – is also there….

Pen feels as if her career has suffered due to her staying true-blue to her culture and heritage, while Neil has, in a phrase, sold out to Whiteness…. It doesn’t help her feelings of inauthenticity that she’s White-passing, biracial, and not registered with her tribe. During a panel dedicated to Indigenous horror authors, Pen lays into Neil for writing a wisecracking misogynist hero who runs around shooting arrows from a quiver strapped to his back, and for succeeding with a book title that she feels is racist (For What Savages May Be).

Neil demurs at this criticism – he declares that, as a fellow Indigenous writer, they should support each other. She suggests to Neil that he ought to write something with “real soul.” The audience disapproves, so Penelope grabs her microphone and chastises them for not accepting her ‘too native’ characters and declares she’ll write a book so good it’ll erase Neil’s name from the history books.

The argument ends when Pen throws a copy of her book at Neil, hitting him in the head hard enough to draw blood and leave a visible scar.

So an allegedly Native author of a romance wherein two Indigenous protagonists argue about Native representation in fiction is, according to a ten-generations-deep search into their ancestry, not actually Native at all.

I’ve reached out to Wilkens and to St. Martin’s Press, and haven’t heard back yet.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·