Reginald Shepherd was very good at first lines. He knew how to thrust his reader immediately into a poem’s motivating dilemma. “The Difficult Music,” the first poem in his first book, Some Are Drowning (1994), begins: “I started to write a song about you, then I decided, No.” The urgency, the confident first person, the intimate address, and the drive to sing: these are all characteristic of Shepherd’s work. So is the abrupt swivel, the negation, the balked song.

Shepherd always stood a little apart. In the 1990s, when “postmodernism” was the name for a new period style, Shepherd was an unapologetic modernist. His idols were Eliot, Stevens, and Hart Crane. “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” which he read for an assignment in ninth grade, gave him an exalted view of poetry as a vehicle for personal transformation, and he never let go of it. Eliot’s poem “took my mundane misery and loneliness and gave them back to me, transformed into words that made my feelings beautiful and important and not mine at all.”

Shepherd had more than ordinary teenage angst to escape from. His biographical note in Some Are Drowning explains that he “was born in New York City in 1963 and raised in housing projects and tenements in the Bronx.” He left this information out of later collections, but he was always clear about where he came from and about the fact that he was Black and gay, even while he mused on whether “gay” or “Black” should come first, since each term left him feeling marginal to the community the other located him in. “For me,” he reflects, “to be black and to be gay have been two radically different subject positions, which to a large extent have contradicted one another, except to increase my sense of the lack of any position called mine.”

He was in a similarly ambiguous position with respect to the modernist poets he took for models. “I owe my formation as a writer,” he observes, to a tradition that is “not ‘mine’ (as a black guy raised in Bronx housing projects).” The language of modernism, Shepherd continues, “both made me possible as a writer and made my being a writer an asymptote,” a role he could only ever aspire to. He was always “haunted by the questions, ‘Can I truly speak this language? Can this language speak through me?’”

Like Eliot’s “Prufrock,” Shepherd’s poems are mental spaces full of echoes, bits of song lyrics, literary allusions, sharp ironies, and uneasy self-commentary. Even when the poem sets forth a scene in the street, a park, or a dance club, it takes place in his head, and the people he writes about are half in his head too. In “The Difficult Music,” Shepherd recalls an incident when “a bum glanced up” and whispered “Nigger, laughing, when I walked by.” As if that verbal abuse amounted to a rape he had somehow been complicit in, he comments, “I’d passed the age of consent, I suppose;/my body was never clean again.” Another type of poet would have built a poem around that anecdote, but Shepherd never settles in one place for long. His rapid shifts of focus, diction, and tone, activated by stray verbal hints and associations, create a pulsing effect, somehow jagged and liquid at once.

The title of “The Difficult Music” refers to that style and the challenges it poses to the reader, who is constantly wrong-footed, hustling to keep up. But Shepherd is also thinking here about something quite different: soul music, which he invokes by quoting a song recorded by Donny Hathaway, “Someday We’ll All Be Free.” Aretha Franklin’s cover of the song, featured in Spike Lee’s film Malcolm X, accentuated its political resonance, making it a civil rights anthem. For Shepherd, modernist poetry and soul music, elite and popular lyricism, both give voice to the yearning to “be free.” But surely we are talking about different kinds of difficulty here. The freedom modernist poetry gestures toward can’t be the same freedom Hathaway and Franklin are singing about. Or could it be? Shepherd’s poetry raises that question and tries very hard to keep it open.

Some Are Drowning is dedicated to Shepherd’s mother, Blanche Althea Berry, whose death when he was not quite fifteen reverberates through his work. She is the addressee in “The Difficult Music,” the “you” he wanted to “write a song about,” the muse and single parent who raised him and his younger sister. “Until She Returns,” the last poem in Some Are Drowning, recalls the devastating hour or “maybe less” it took the teenage boy to pack up “all my cares and woe in a plastic/garbage bag” while her “personal effects” were “incinerated, with no one to say/mine.”

As Shepherd explains in a prose memoir, his mother had moved from the South to New York City to “better herself,” but she “just ended up a poverty statistic, part of the Moynihan Report on the breakup of the black family.” Meanwhile, she passed along her project of betterment to her son. Even before he was born, she bought for him a set of encyclopedias and a “lavishly illustrated” history of the Renaissance. When he learned to read and write, he excitedly “wrote my name over and over again on the living room mirror with a tube of my mother’s lipstick.”

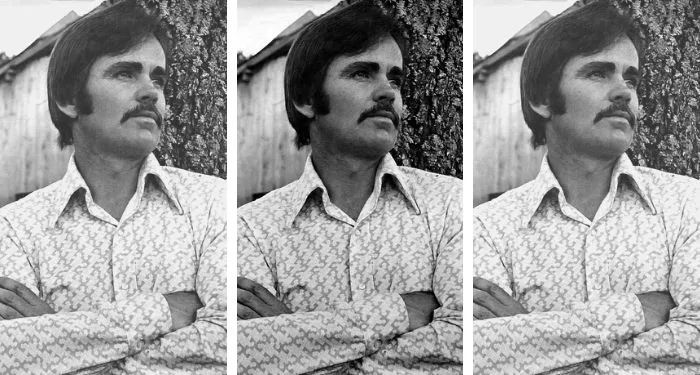

She insisted he was “smarter than 99 percent of the people on this planet,” and saw to it that he won a scholarship to a private school. When he left that school after being bullied by his white classmates, she made sure he was supported as a “special” student by the State of New York. After she died, Shepherd was sent to live with the “dirt-poor” relatives she had left behind in Georgia. “Sleeping on a rollaway bed in the den in a three-room house crammed with eight people,” he “burrowed deeper into books than ever before.” Books would take him to Bennington College, Brown, the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and eventually a better life as a poet and a teacher of creative writing. Looking back, he realized he had no pictures of himself prior to his first author photo.

But the life he created for himself through literature came with “a certain survivor guilt.” Shepherd’s poetry was initially driven “by an impulse to rescue my mother from her own death and from the wreckage of her life, out of which I emerged, in both senses of the word.” She is one of the “drowning” evoked in the title of that first book. The image situates her difficult life and early death in the history of the Black diaspora, beginning with the Middle Passage and “slaves thrown overboard to reach the new world,” as he puts it in one of his poems. In later poems, Shepherd associates his mother with images suggesting the hardship, beauty, and mystery of Black life. In “My Mother Was No White Dove,” she is “the clouded-over night,” “the murderous flight of crows,” an “obscure bruise across the sky/making up names for rain.” In “For My Mother in Lieu of Mourning,” she is the “brackish water” of sleep and dreams in which her son tosses and turns: “Black, opaque, impossible to see through//to the bottom, swim across to shore.”

As a child, Shepherd read deeply in science fiction, fantasy, and mythology. He was especially fascinated by Greek gods and heroes. They were splendid beings “to whom moral or ethical categories don’t apply, any more than they apply to hurricanes or tornadoes or sunrises or the light of the full moon over saltwater.” They helped him understand himself and his world and in time became a resource for his poetry, where Narcissus, Apollo, and other mythic characters regularly appear.

In “Orpheus Plays the Bronx,” a poem from Fata Morgana (2007), “Tanqueray bottles/halo the bed” where his mother is sleeping away the weekend, having “tried/to kill herself.” Her young son studies a book of myths in which a poet “turns around/inside the mouth of hell to look at her/losing him.” The Eurydice who is his sleeping mother has been poisoned not by an asp but by “a handful of pills.” The radio is playing Al Green, Barry White, and Rick Astley, whom Shepherd quotes singing “never never gonna give her/up, or back.” But that’s not how the story goes. Recognizing his mother’s sacrifice as the cost of his creativity, Shepherd faces bitter truths: “The man can’t live if she does./She survived to die for good.”

The “drowning” people Shepherd was desperate to rescue included “always myself.” The threat of oblivion was constant and general. “I have,” he explains, “a strong sense of things going out of existence at every second, fading away at the very moment of their coming into bloom…. In that sense everyone is drowning, everything is drowning.” But in his poems about gay sex from the 1990s, before antiretroviral drugs made HIV infection more like a chronic illness than a death sentence, the threat is very specific and intertwined with sexual desire. “How afraid I am,” he writes in “Kindertotenlieder,” “of your outstretched hand, its petals/white and black and falling fingers.”

Shepherd died in 2008 not from AIDS but from colon cancer. He was forty-five, slightly older than his mother had been at the time of her death. He had published five books of poetry. A posthumous volume, Red Clay Weather, followed in 2011, edited by his partner and literary executor, Robert Philen. Now The Selected Shepherd, edited and introduced by Jericho Brown, returns this body of work to view. Sampling poems from all six books, sensibly arranged in the order in which they first appeared, Brown’s choices capture the arc of Shepherd’s poetic career and the range of his formal experimentation. Still, the selection is probably too selective, since Brown prints just seventy-seven of the 306 poems in Shepherd’s books. “Skin Trade,” included by Adrienne Rich in The Best American Poetry 1996, and “You, Therefore,” a love poem singled out by Reginald Dwayne Betts as a special favorite, are just two of many strong candidates that did not make the cut. “You, Therefore” begins with a line almost as arresting as the address to the reader in “This Living Hand,” by Keats: “You are like me, you will die too, but not today.”

The difficulties posed by Shepherd’s poems are by no means purely stylistic, and Brown doesn’t shrink from them. If anything, his choices foreground the central challenge: Shepherd’s psychologically and politically complicated desire for white men. The poems anticipate objections. Shepherd knows “you would say that all along/I chose wrong, antonyms of my own face/lined up like buoys.” He knows the beauty that stirs him is illusory. These “perfect instances of bodies last only/for the instant, or until last call,” and, he admits, “I hate every lovely thing about them.” Punning on the Latin root of “candor,” meaning “whiteness,” he asks himself and everybody else, “Why worship whiteness always, what virtue/in that candor, what quality?” Yet he remained, in poetry as well as in life, a self-declared “snow queen.” “Don’t try/to say you didn’t know the gods are always white,” he quips, “the statues/told you that.”

Shepherd was writing in an ancient lyric tradition in which envy, inconsolable longing, and the simultaneous presence of love and hate are conventional. (See his “Sappho’s Fragment Thirty-One Revised.”) He understood his preference for white men as an instance of a universal principle: “One desires what one does not have, one desires what one is not. Desire is the mark, the wound, of that lack.” But the history of white supremacy was an inescapable frame and defined his desire in particular ways, no matter how conventional its expression or putatively universal its structure, as he was acutely aware. In “The New World,” a frat boy wipes his face with his T-shirt, revealing “peaks of nipples/briefly glimpsed before the cotton field unfolds.” In “Nights and Days of Nineteen-Something,” a poem that mocks the exquisite taste of similarly titled poems by Cavafy and James Merrill, Shepherd writes:

I never wanted him

to ask anything of me but suck my big

white cock. I come home sticky with

his secrecies, wash them all

off. You were my justice, just my means

to sex itself, end justified by the mean

size of the American penis.

This scene could not be much more sexually explicit, and to that extent it seems “realistic,” but it might also be read allegorically. Are Shepherd’s objects of sexual worship not stand-ins for the big white classical tradition and the modernist poets he loved? Are his relations to the men he desires and the literature he loves not similarly structured?

The answer is: yes and no. In poetry and prose Shepherd alludes to an epigram by Stendhal from his treatise De l’amour: “La beauté n’est que la promesse du bonheur.” Sex and poetry were both versions of that promise. Both involved the pursuit of “beauty.” Both held out the possibility of “happiness.” But that doesn’t mean they were identical. It matters that the “gods” are wearing “backwards baseball caps” in Shepherd’s poems. By investigating racialized scenarios of desire and abjection, Shepherd gains a kind of reverse mastery over his fetish objects. He noted in an interview that it was possible if not irresistible “for ‘whites’ to believe they have attained to whiteness.” This Black poet knows better. Whiteness is a fantasy impossible for anyone to possess, a stupid beauty that takes its authority for granted and mistakenly assumes the body it inhabits is natural and complete. That boy in the cotton T-shirt “won’t comprehend these lines” and is therefore ultimately irrelevant. In fact, Shepherd adds coolly, “I have already misplaced his name.”

In addition to being a poet, Shepherd was a sophisticated literary critic who wished “to play a role in the renewal of relations between poems and ideas.” He was reacting to what he saw as a tendency in criticism to reduce poetry to formal effects and affective impressions while privileging feeling over thought and the personal and psychological over the philosophical and political. His two books of nonfiction, Orpheus in the Bronx (2007) and the posthumous A Martian Muse (2010), which was edited by Philen, share the subtitle “Essays on Identity, Politics, and the Freedom of Poetry.” They both collect personal memoir and reflections, speculation on literature and culture, and responses to the work of individual writers. They show Shepherd using prose polemic to assert the intellectual power of poetry and clear a space for his contrarian poetics.

During the 1980s, when he left college for a period and was doing dreary clerical work for the Boston Public Library, Shepherd read a great deal of theory. Saussurean linguistics confirmed his sense of the distance between names and things. He studied Freud and Lacan, Derrida and Foucault, in xeroxed pages during lunch breaks. The work of the Frankfurt School mattered most:

From writers like Adorno and Benjamin I came to understand that the alienation I felt was not my personal burden or treasure (it felt like both), as a black gay intellectual/artist misfit college dropout with a shitty job and no boyfriend, but rather an integral part of the social-political world I was at once within and outside of, a general condition of life under capitalism. I was not so special as I’d imagined myself to be, but I was also not so strange.

Shepherd probably found Stendhal’s epigram about beauty in Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory, where Adorno glosses it by saying “art does its part for existence by accentuating what in it prefigures utopia.” That idea ratified Shepherd’s youthful experience of reading poems like “Prufrock.” “Freedom,” he writes, is what “Kant called the kingdom of ends, in which people and things exist for their own sakes and not for the sake of profit or power.” Poetry was an image of that condition. Music also “hints at that, even promises it, but never gives it for more than a few moments.”

The crucial principle for Shepherd was art’s autonomy, a modernist idea. Many if not most writers today who have a progressive political orientation would reject that principle out of hand, believing in the social embeddedness of art and feeling the responsibility to community and collectivity that comes with it. So it is striking that Shepherd defended autonomy in political terms: it is the precondition for art’s “liberatory and utopian possibilities.” This doesn’t mean he thought art should use its freedom to paint pretty pictures. Adorno held that, because the “utopic element in society is constantly decreasing,” art “must break its promise in order to stay true to it.” This is where the poetics of difficulty come in. Art manifests its freedom and renews its promise in its resistance to easy, instrumental communication, expressed through everything that makes a Shepherd poem slippery, spiky, hard to digest.

Shepherd had no desire “to subvert or overthrow the ‘canon,’” which he felt was a fictional construction to begin with. “In my work,” he explained,

I wish to make Sappho and the South Bronx, the myth of Hyacinth and the homeless black men ubiquitous in the cities of the decaying American empire, AIDS and all the beautiful, dead cultures speak to and acknowledge one another.

He published essays about such writers as Wilfred Owen, Jean Genet, Paul Celan, his Bennington teacher Alvin Feinman, Jack Spicer, Tim Dlugos, and Jorie Graham. But apart from a few respectful sentences about Gwendolyn Brooks, he has almost nothing to say about African American writers. He did not find common cause where he might have, for example in a Black gay poet of his generation like Essex Hemphill.

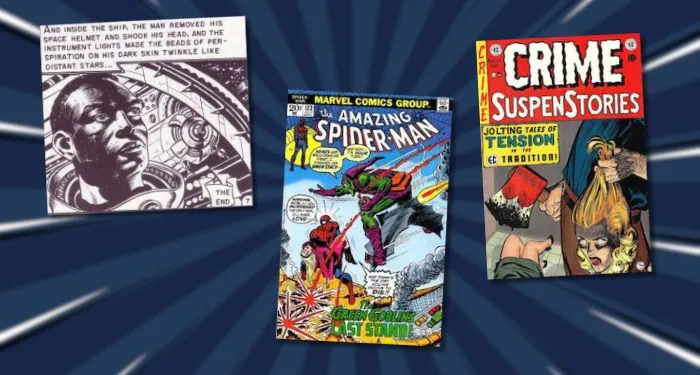

An exception is the science fiction writer Samuel R. Delany. Delany’s “alternative worlds” offered Shepherd an imaginative “freedom from the tyranny of what is, the domination of the actually existing.” For Shepherd, that meant primarily freedom from sex and gender norms and, perhaps more urgently, the cultural expectations imposed on Black identity. Delany, he writes, “helped me navigate the treacherous waters of being a writer who is black” and uncomfortable with “the not-various-enough approved modes of how to be a ‘black writer,’ of what counts as ‘black literature.’” Shepherd found in Delany’s novels people “unlike any people I knew or previously could have conceived” and some “who weren’t people at all. That unlikeness felt true.”

What was the basis of Shepherd’s passionate resistance to identity labeling and his idealization of experiences of “non-identity”? Was he committed to a racial antiessentialism and/or a radical intersectionality that made the “unlikeness” of Delany’s inventions “feel true” to him? Or was his repudiation of “identity poetics,” which he called “boring” (without naming any names), an instance of internalized anti-Blackness, a case of self-hatred? When it came to labels, he was much more anxious about being pinned down by “Black” than by “gay.” In fact, he continued to use “gay” to describe himself and other people when the more flexible “queer” was not only available but increasingly preferred in the identity debates he was entering into.

“A black writer in the Black Arts or even the Harlem Renaissance mode,” Shepherd complained, “is expected to celebrate her or his nappy-headed, Afrodiziak, freaky deaky and very much other culture and self (and there is little distinction made in this mode between culture and self).” What is notable here, besides how worked up Shepherd got when the subject was the proper conduct of a Black poet, is his objection to the standardization not only of Blackness but of what it means to be “other.” “Other” is the category he was identified with and invested in, an oppositional and contingent identity, strictly relational by definition, that evades the representational logic usually governing identity: the box left when you’re refusing to tick boxes. He didn’t want to see this category turned into a cliché or commodity.

The title of his most astringent and adventurous poetry collection is Otherhood (2003). Otherness represented for him indeterminacy and possibility. For this reason, it was the special province of poetry. “Poetry’s preservation of mystery,” Shepherd writes, “is its preservation of a space not colonized by capitalism’s totalizing impulse” and the logic of “instrumental reason.” Poetry, especially the modernist poetry he discovered as a teenager, held out “the possibility that life could be otherwise, that I could be otherwise.”

It might be objected that poetry is too marginal an art form in contemporary America to worry about its being co-opted to “capitalism’s totalizing impulse.” But that, Shepherd thought, is exactly what even well-intentioned demands for “relevance” did by calling for accessible, preapproved, civically useful meanings. And while it’s true that poetry with a well-defined progressive political program is also dedicated to “the possibility that life could be otherwise,” Shepherd was not interested in the pragmatics of alliance and amelioration. He valued poetry as “a palpable instance”—not merely a representation—“of nonalienated existence.” He was interested in utopia, the most radical “otherwise” imaginable.

“I don’t trust beauty anymore,/when will I stop believing it?,” Shepherd asks in the early poem “Paradise.” He didn’t “trust” beauty because the concept (along with the rest of Western aesthetics) belonged to “the histories of high achievement while my/great-grandparents were hidden among the cotton,/slaves.” But he never stopped “believing it.” That belief in beauty put Shepherd at odds not with minority writers exactly, let alone with a so-called mainstream poetry he found too intellectually uninteresting even to polemicize against, but with the avant-garde. When his career took shape, Language poetry was the dominant alternative movement in American poetry, and the hallmark of its vanguardism was a critique of lyric subjectivity and traditional aesthetic categories like “beauty.”

Shepherd’s animus is surprising considering the complicated status of the “I” in his poems and the fact that Language poetry launched its critique of the lyric backed by Marxist theory and a class-based politics wholly congenial to him. The avant-garde didn’t like identity poetics any more than he did. So why not get along? His distaste for the “avant-gardeners,” as he called them, reflects his instinct, à la Oscar Wilde, to reject any group with which he seemed to agree. The more important factor, however, is that Shepherd remained invested in aesthetic categories like “beauty” even while he questioned them, and the avant-garde critique shifted the balance in his ambivalence. He dug in and defended what he didn’t “trust,” knowing that “without a notion of beauty, an embodiment of the possible beyond the abjections of the mundane, I would not have become a poet, would not, perhaps, have left behind the Bronx housing projects and tenements at all.”

By the early 2000s contemporary poetic practice no longer seemed defined by a war between the lyrical and the avant-garde. There was talk of “Third Way” and “New Lyric” poetries that broke down a false (or by this time tedious) opposition. “Post-avant” was the cheeky term Shepherd adopted and put to his own purposes in a series of Poetry Foundation blog posts in 2008. He defined “post-avant” poets this way:

They incorporate fracture and disjunction without enthroning it as a ruling principle. They are interested in exploring, interrogating, and sometimes exploding language, identity, and society, without giving up on the pleasures, challenges, and resources of the traditional lyric. Their work combines the lyric’s creative impulse with the critical impulse of Language poetry.

Though far too bland and general to do justice to it, this is not a bad description of his own work. Shepherd had never done “the things that one should do to be successful.” He hadn’t “networked” or “schmoozed.” He was no one’s protégé, and he had never belonged to “a clique or club” or held a tenured teaching position. But he was not so alone in his practice anymore.

In the same post Shepherd announced the publication of a book he had edited, Lyric Postmodernisms: An Anthology of Contemporary Innovative Poetries. The title pointed to the long-standing tension between traditional and experimental poetries and suggested a new synthesis. The book showcased a wealth of new writing that demonstrated values Shepherd had espoused for twenty years. In keeping with his intellectual ambitions for poetry, he printed artist statements as well as poems by his twenty-three contributors, who included Susan Stewart, Forrest Gander, Peter Gizzi, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Cole Swensen, Elizabeth Willis, Brenda Hillman, Rosmarie Waldrop, and Nathaniel Mackey. These and other poets featured in the anthology have since won major literary honors, taken on leading roles in MFA programs, served on prize committees and advisory boards, and generally distinguished themselves. Shepherd might well have achieved similar stature and influence had he survived his illness and continued to write poems and prose.

As one opens The Selected Shepherd, it is possible to feel his time has come. No one calls it that, but “post-avant” poetics remains the order of the day. If you didn’t know anything about Shepherd and took his poems to be brand new, you might think he had been reading Jericho Brown and any number of other poets born after him. How he would have hated being so fashionable! Well, yes, he would have loved it too. But he would have found plenty to dissent from in the current landscape, presumably. The fact is, no matter how much he shares with other poets today, there is no one with Shepherd’s nervy combination of the refractory, sassy, and plangent, the witty, sorrowing, and unappeased, no one so torn up and twisted in the face of what he loves. If there were, Shepherd would turn on his heels and say something different, because that is the whole point of poetry as he understood it.

Despite all of his talk about transformation and the good of “nonidentity,” Shepherd’s poetry is nothing if not personal, and therefore very Black and gay, and he knew that. When he quotes T.S. Eliot declaring poetry to be an “escape” from personality and emotions, Shepherd calls attention to Eliot’s “marvelously bitchy” qualification: “But, of course, only those who have personality and emotions know what it means to want to escape from these things.” So much for the autonomy of art.

The politics of such a conflicted sensibility are necessarily vague and deferred, with much riding on the enigmatic power of certain images. It was impossible for Shepherd to find the right image to represent (and in that sense “rescue”) his mother; and that impossibility was productive, the starting place for his poetic career. In “The Difficult Music,” he says to her: “Some drift/always takes your place.” At the end of the poem, he is thinking of Adorno and utopia, listening to the music his mother listened to, and—skeptically, self-consciously, but hopefully, too—humming along:

Take it from me, my stereo claims, some day

we’ll all be free. If anyone should ever write that song.

The finely sifted light falls down.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·