Swimming pools, whether in paintings by David Hockney and Eric Fischl or in unsettling films such as The Swimmer (1968), based on a John Cheever story and set—but where else?—in Connecticut, have always excited me. In The Swimmer, Burt Lancaster plays Ned Merrill, an evenly tanned ad executive who swims across eight miles of backyard pools to reach his house, encountering bizarre, well-heeled neighbors along the way. La Piscine (1969), a sexy French thriller, takes place around a swimming pool on the Côte d’Azur and features gorgeous actors like Alain Delon and Romy Schneider. In the 1969 movie based on Philip Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus, the first time Neil Klugman spots the beautiful, nose-bobbed Brenda Patimkin, she is poolside, where she asks him to hold her glasses. (In the novella, Roth memorably observes Neil’s instant infatuation with this entitled suburban mermaid: “She caught the bottom of her suit between thumb and index finger and flicked what flesh had been showing back where it belonged. My blood jumped.”)

Among my favorite movies featuring swimming pools—of which there are many, including 3 Women (1977), Sexy Beast (2000), and Fat Girl (2001)—perhaps the truly quintessential one is The Graduate (1967). In it, Benjamin Braddock spends his post-college summer idling in his parents’ pool, a major status symbol at the time (somewhat equivalent in this inflationary moment to having a private chef), looking for a meaning to life beyond the vapid bourgeois aspirations of his parents and their friends. When his father asks him what, exactly, he is doing, Ben’s despondent, Zen-like reply underlines his sense of lostness: “Well, I would say that I’m just drifting here in the pool.”

The possibility of yielding to the embrace of water goes far back, as Bonnie Tsui reports in her book Why We Swim (2020). It held appeal for Leonardo da Vinci, for instance, who sketched swim fins and snorkels. Tsui also notes that during the 1750s, when a belief in the curative effects of immersion in cold water was much in vogue, Benjamin Franklin, “an avid skinny-dipper for much of his long life” (hard though this may be to envision) took daily swims in the Thames. Lord Byron was entranced by swimming, which freed him from the encumbrance of his clubfoot, and according to Tsui he “entertained the thought of having been a merman in a previous life.” In 1810 a twenty-two-year-old Byron crossed the Hellespont, the tumultuous four-mile strait in Turkey that separates Asia from Europe, now called the Dardanelles; he dedicated a lyric poem to this feat, “Written After Swimming from Sestos to Abydos,” and also referred to it in Don Juan.

Franklin Roosevelt had a pool installed in the White House in which he swam several times a day as therapy for his polio, and John F. Kennedy made frequent use of the pool when he was in office to alleviate his constant back pain and reportedly to seduce young women. When the more puritanical Richard Nixon moved in, the pool was boarded up to make way for the press room. During his administration the exercise-minded Gerald Ford had a pool and cabana installed on the South Lawn, despite opposition from his advisers, who thought it might imperil his reelection, especially given that he had stressed budgetary restraint when he took office in 1974. In 1997 the fun-loving Bill Clinton added an aboveground, seven-foot hot tub beside the pool, which conduce to make the White House sound less like a serious place where national policy is hatched than a playground for powerful people to frolic in.

I love the way swimming pools wait expectantly—rectangular, round, L- or kidney-shaped, sparkling in the sun, the water sapphire, cerulean, indigo, or, less often, deep gray or viridian green—inviting you to plunge in. The newer style in swimming pools is seawater instead of chlorinated water, and then there are infinity pools, much featured in high-end hotels, which create the illusion of nothing between you and the horizon. Pools require less grit than the ocean, where giant waves, jellyfish, and undetected sharks can terrorize you. The last time I took a serious swim in the ocean was nearly a decade ago, on Martha’s Vineyard, where I got caught in a riptide and flailed around, trying to break free, until a friend came to the rescue after I started feebly (and embarrassingly) calling for help.

*

Freud believed that water imagery, as it appears in dreams, is connected to birth and fantasies of intrauterine life, the existence within the womb. That may be part of the allure of swimming pools, which seem to suggest that you can begin your life anew in a buoyant state, that your conflicts and doubts will slide off you, leaving you weightless and unimpeded. It is even possible that something spiritual or inscrutable might happen in a pool, like the sort of crisis of faith that is produced in Mrs. Moore by the disturbing echoes in the Marabar Caves in E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India, or like the transformation in Cocoon (1985), a science-fiction movie in which a group of residents from a retirement home become teenagers after bathing in a pool filled with alien cocoons.

One of the most thrilling moments of my childhood came in 1964, when my family sold our summer place in Long Beach, a town on the South Shore of Long Island that was run-down at the time, and bought a house in tonier Atlantic Beach that had a swimming pool all its own. I was ten years old, not yet worried about how good I looked in a bathing suit, and ecstatic at the thought of having a pool on tap in the garden. No more splashing around in Long Beach’s public pool, filled with screaming kids and overchlorinated water, the better to drown out the smell of urine. On top of those hazards, I was afraid of bumping into or being capsized by another swimmer, so I had to keep a vigilant watch, which was hardly relaxing. Of course, I might have made friends in the pool, but I always came with my many siblings, and our caretaker always kept her dour eye on us. I do remember casting admiring glances at some of the lifeguards, muscled types who reigned over the pool from their high perches, but they genially ignored me except when they blew the silver whistles that dangled on their chests to warn me off the deep end, where I liked to believe I could hold my own but patently couldn’t.

The pool in Atlantic Beach was pristine and quiet, a turquoise receptacle that led me to change into one of my worn-out, overstretched bathing suits (I had two older sisters, and my mother was a big believer in hand-me-downs) and swim energetic laps or lie on my back to my heart’s content. Quelle merveille! My family, however, was Orthodox, and to my immense sorrow there was a ban on swimming each week for the twenty-four hours of Shabbos. This had partly to do with preserving the undefiled, tranquil spirit of the day and partly to do with the prohibition against carrying on Shabbos (unless there is an eruv, a symbolic boundary, usually a thin wire, that allows observant Jews to carry items or wheel strollers), which raised the problem of carrying water upon getting out of the pool. Talk about the narcissism of small differences.

At some point in my adolescence, markedly later than most of the girls around me, I sprouted large breasts. They stood out more than they otherwise might have because of my narrow hips, and made me feel uncomfortable instead of proud, especially when one of my nephews asked me why I had such “big boobies.” (Years later I elected to have a breast reduction, a decision I have come to regret.) I started assessing my body in a mirror before I went out to the pool, making sure that I looked properly naiad-like. Because of my mother’s insistence on feminine modesty, in keeping with her Germanness and the Orthodox attitude regarding tznius—revealing too much flesh—I was restricted to wearing one-piece bathing suits instead of bikinis. Later on I would come to prefer the sly eroticism of one-pieces to the brassy come-hither look of bikinis, but at the time it seemed like yet another trying rule in a household that had too many rules to begin with.

The Atlantic Beach house was eventually sold, despite my protests, more than three decades ago, leading me to make do by going to friends’ houses for the weekend and swimming in their pools, or the ocean or the Long Island Sound. By that time I had become panicked at the thought of wilting in the city all summer—a privileged anxiety, to be sure, but one that had been fostered in me by the circumstances of my background. About fifteen years ago I started renting houses or condos in various parts of the Hamptons, a few of them with pools of their own. I couldn’t afford anything remotely near the ocean, and sometimes wondered why I had taken the Jitney for three or four hours only to end up in a house with a lawn that looked like it might as well be in Forest Hills.

*

So on a broiling Sunday in July, I am lying on a poolside chaise, having maneuvered it for maximal sun exposure, the better to inhale the rays, despite the much-publicized risks that come with tanning. The pool in question is a shared one, part of a condo community in Southampton where I have rented an attached townhouse that doesn’t admit much natural light. (Apparently the owners have never cracked the spine of a book, and I have had to resort to schlepping two standing lamps from the city.)

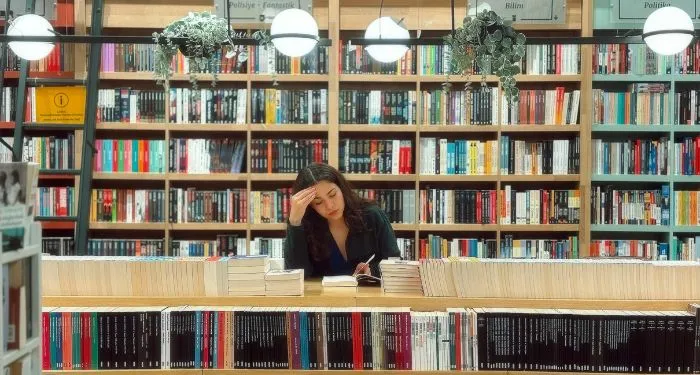

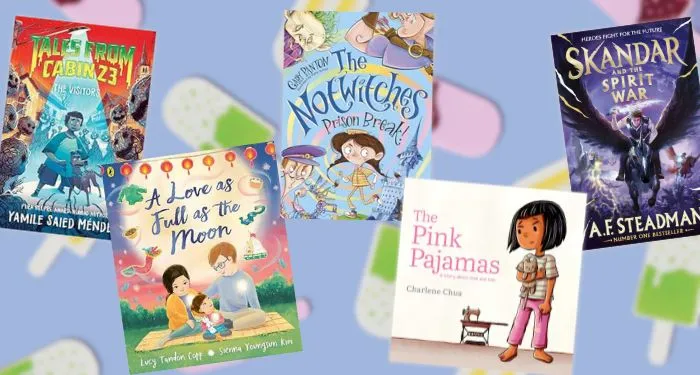

I am reading one of the esoteric, nonescapist books I incline toward—a literary novel or a biography of some famous writer’s overlooked first wife—while listening to Spotify with my earbuds, delighting when Loudon Wainright III’s “The Swimming Song” comes on. It is, fittingly, my favorite song of his, nudging out “Dead Skunk” for first place. “This summer I swam in a public place,” he sings in his pleasant, slightly disaffected voice. Around me, children of various ages shout and splash. “That’s mine,” one little girl in a spangly bathing suit says commandingly to another little girl who is clutching an inflated plastic tube. “You have to give it back to me.”

Directly next to me are two couples who look to be in their sixties. They sit rather than lie on their chaises and loudly discuss the merits of a new restaurant they have both recently tried. “The chicken was overcooked,” one of the women, wearing a black one-piece and gold bangles, says. “I could tell from the minute they brought it out.” From what I can gather, both couples live in Westchester and have owned their respective summer condos for years. They move on from food to discussing a granddaughter’s Bat Mitzvah and how extravagant it was, but what can you do?

I feel like a misfit, a rarefied, lone creature out of step with people who know how to enjoy the simple pleasures of life. I am suddenly thrown back to a memory of four or five decades ago, to the enormous rectangular swimming pool at Grossinger’s, the iconic kosher hotel in the Catskills, one of the largest of the Borscht Belt resorts. Jewish families went there for the summer and religious holidays to dine on vast quantities of food, one of the things the place was famous for, and to take part in a daily schedule of activities, like guided hikes, tango classes, bingo, and amateurish nightclub acts. The nightclub, called the Terrace Room, was cavernous, as was everything in the hotel, including the dining room, which could seat 1,300.

During the Seventies and early Eighties, Grossinger’s was also where nubile Jewish girls went to meet boys, whom, if all went as planned, they might eventually marry and divorce. There was a particular summer weekend, known as Shabbos Nachamu, which came right on the heels of Tisha b’Av, a fast day commemorating the destruction of the First and Second Temples, that had been designated as the singles weekend. The scene at the pool was like a less athletic, paler-skinned Baywatch, the TV show that featured Pamela Anderson and a bevy of blonde and bronzed beauties along with a sprinkling of goyish, cute-featured boys who all looked dumber than dumb.

I had felt like a misfit at Grossinger’s as well. I was too neurotic and self-conscious to compete with my seemingly less impeded friends, who strolled up and down with their own less-than-perfect bodies and flirted blithely with boys, who were often short and always dark-haired, and some of whom wore crocheted yarmulkes even to the pool. Their names were frequently biblical—Joshua, David, and Samuel—linking them unmistakably to their origins.

I flirted not at all, remained glued to one of the chairs packed tightly by the pool, and every so often got up to swim laps; I had a strong crawl but had never learned to breathe correctly, so I was forced to take quick, gulping breaths between strokes. After I was done I would return to my lounge chair as if I were competing in some important event, without time to engage in socializing before the next match. It wasn’t a choice so much as a wish to avoid the intricacies of the mating game, although there came a summer when I did actually meet someone at the pool, an Argentinian with startlingly blue eyes who lived in Israel and seemed initially indifferent until he flew in the following fall to keep our hotel romance alive.

Although I never considered myself the Grossinger’s “type”—the sort of twenty- or twenty-five-year-old who came to the hotel with suitcases of clothes, prepared to preen and conquer—I find myself remembering my weekends there with affection. For one thing, I always went with a good friend, with whom I traded gossip about who was sleeping with whom and who was destined for spinsterhood. One of these friends, who was from a similar Orthodox background, came back to our room late one night on a Shabbos Nachamu weekend and confided to me that she had lost her virginity, helped by having smeared peppermint-flavored toothpaste on her vagina, a sensual tactic she had read about in Cosmopolitan. I was both shocked by her wantonness and admiring of her strategy and wondered why I lacked the ingenuity—or was it the firmness of purpose?—to follow suit.

*

This summer, the gleaming, Olympic-size Gottesman Pool opened near Harlem Meer, on the north side of Central Park, giving greater swaths of the general public access to the joys of swimming. It accommodates up to a thousand swimmers, includes lockers and picnic benches, and provides lessons and programs for free; in the winter it converts into an ice-skating rink. I will probably never go there, although it would undoubtedly be good for me to expand my aquatic horizons. There was recently an essay in The New York Times in which the writer sang the egalitarian praises of public swimming pools, which led me to wonder, guiltily, if I am an irredeemable snob or a misanthrope when it comes to pools.

Meanwhile I have returned to a house I rented two years ago, on the slightly cramped side but prettily done up in beachy shades of light blue and white. This house has a nicely landscaped, kidney-shaped pool, which I must descend into cautiously these days, given my arthritic shoulders and knees, and always under the watchful eye of a friend. I still love lying poolside and am struck anew every morning by the water’s glinting, dimpled blue surface. I let myself drift in and out of my thoughts, daydreaming about past lovers and abandoned plans, musing on, among other things, why and how I have ended up here, at my advanced age, in a rented house situated in a village I don’t much like and in which I know very few people, all for the sake of a swimming pool to call my own, at least temporarily.

But something has changed, or shifted, although it’s hard to put my finger on what, exactly. Perhaps it’s that the world impinges too much these days—my phone, the ever-more alarming news, the unstoppable Substacks and podcasts, an overwhelming, seemingly futile sense of despair. The current resident of the White House has no use for the swimming pool on the South Lawn, busy as he is reshaping the world according to his grasping, malevolent vision. Even in the sun, the shadows lengthen.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·