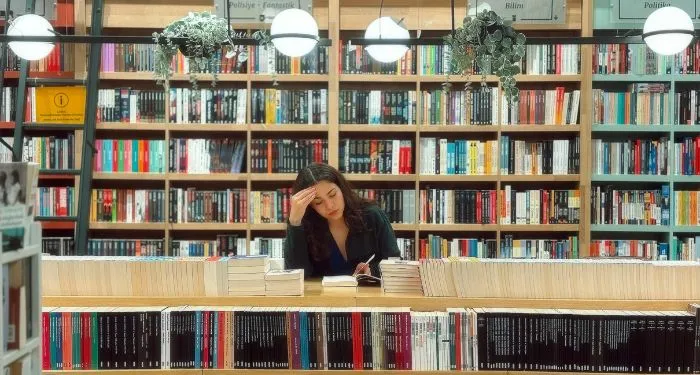

This conversation begins with the poet, writer, and translator Daisy Rockwell reading her poem “The Music Metaphor.” For translators, the question entertained by this poem arises all the time, though in many different forms and situations: How do we decide which translations are better than others?

To answer this question, the two publishers on this panel, Jacques Testard of Fitzcarraldo Editions and Adam Levy of Transit Books, talk through how they each evaluate commissions and acquisitions, and how they navigate the editing of translated work. And, because so many of the guests on this show have served on prize juries, we all came to compare our experiences making judgments that can feel at once arbitrary and hugely consequential.

Daisy Rockwell: “The Music Metaphor.”

Suite I:

I’m so excited, she says.

What, he asks.

Yo-Yo Ma’s Bach cello suites is out on vinyl,

She says.

Amazing, he replies,

I love Yo-Yo Ma.

Same, she says.

Suite II:

I’m reading War and Peace, he says.

Which translation, she asks.

Does it really matter, he counters.

They’re very different, she snaps.

Oh, he says. Constance Garnett.

She grimaces.

What, he asks.

There are much better ones, she explains.

Does it really make a difference he asks,

dropping the heavy book on the coffee table.

It’s still the same book, right?

Of course, I don’t even know if I trust translated literature,

he adds.

It’s probably only good in Russian.

Why don’t you say that about Bach, she asks.

What do you even mean, he responds.

Why would you listen to Yo-Yo Ma playing Bach, she snaps,

I would only listen to Bach playing Bach.

I see what you did there,

he acquiesces.

Suite III

In this metaphor

Bach is the author

And the translator is Yo-Yo Ma.

Merve Emre: I imagine there are some people who don’t know how a work of translated literature gets published—how Bach and Yo-Yo Ma are brought together. I’m wondering if our two publishers could walk us quickly through the process.

Adam Levy: Daisy’s poem reminds me of a conversation I had the other day on the street in New York City with a guy who was hitting on my sister.

The way that the acquisitions process works for us is pretty similar to other houses, large and small. We receive submissions directly from agents, both American agents and international ones. We receive submissions directly from translators. We have an open reading period occasionally, during which we consider a group of translations from translators who don’t necessarily have a way into the industry. We also have meetings and relationships with foreign rights directors at international publishing houses who frequently submit titles to us and whom we meet with at international book fairs. We also do a good amount of sleuthing on our own. We read around, guided by our own interests and curiosities and what we hear from other readers or writers we trust and admire. Once we have a set of submissions, we talk about it internally at a weekly acquisitions meeting among our small team of editors. Then we’ll make decisions either in favor or against.

Emre: Jacques, is there anything you want to add to that?

Jacques Testard: In the early days of Fitzcarraldo, which is now ten years old, when it was just me publishing only six books a year, there was much more proactive sleuthing. I was reading lots of authors, predominantly in French because I grew up bilingual and have always read indiscriminately in French and English. French publishers translate much quicker, so there was a lot of stuff translated into French that I had access to. Quite a few of the authors in translation that I acquired at the beginning were authors I first read in French.

For me and for my colleagues, the role of the translator is more important than the agents and the rights directors. If we get a tip from a translator who understands our taste, or who we’ve worked with before, or with whom we have an affinity. We tend to pay attention to that more than to a submission from an agent or a foreign publisher. The international network is also very important. Editors at foreign publishing houses—whether in the US or in France, Spain, Germany, Italy—are people with whom we share authors and a literary sensibility. If they recommend someone or if they’ve acquired someone, that will be a reason to pay attention. There’s also the timing. You need to receive a tip or a submission when you’re going to have the time to give it attention.

Emre: Adam, in our last episode, you said that when you were thinking about acquiring a work for publication, you might be deterred if the work did not align with the politics of the imagined audience of Transit Books. What did you mean by that? How do you balance whatever your personal judgment might be of the work and your anticipation of who might be reading it?

Levy: I don’t know that I make that distinction so significantly. At a small house, the people who are acquiring and editing are also marketing and pushing the book out into the world. The impulse to acquire is the same animating force that propels a book through the marketing and publicity process. For me, that initial excitement is the test.

Emre: How do you know what excites you?

Levy: Obviously, it’s an incredibly subjective thing, and every independent publishing house prides itself on the narcissism of small differences among tastes that in a macro way look pretty similar. We’re looking for voices that feel new and fresh and have a certain texture to their language. We’re looking for things that push the boundaries of prose and take certain kind of risks on the page. That’s the kind of thing that you can feel really quickly, especially in a translation where you’re only seeing, say, a twenty-page sample, sometimes even less than that. You can feel whether this prose or this voice is something that you want to stick with. When I commission a report after that, sometimes all I care about is if this voice able to sustain itself. Is the author able to deliver on his initial promise? If the answer is yes, then to me that’s a sign that it’s a book that’s worth investigating further, if not signing outright.

Emre: What about the politics of your imagined audience?

Levy: It’s not like I have a specific demographic in mind. Say we’re getting a book that is considered groundbreaking for its depiction of a feminist voice in a country at a certain political moment, and that voice and the feminism that it’s describing feels kind of late to arrive in the US where we might already have litigated these theoretical points in decades past. In that case, I would say that the politics doesn’t neatly map onto ours. To be concrete, it’s a contemporary, somewhat-left-progressive political world view that we’re considering, which is largely my own politics.

Emre: Have you turned down books for not checking the progressive politics box?

Levy: One hundred percent. All the time.

Emre: Jacques, does what Adam is saying square with how you think?

Testard: It is totally subjective. We are editorial-led, as Transit is. For me, it’s always about the quality of the text, and it always will be. We would never, ever think about or even discuss an imagined audience. That kind of thing comes later, if at all. To quote the narrator of Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station: we’re looking for an authentic experience of art. Sometimes you read something that you really weren’t expecting to like, and you get that kind of tingling feeling, and you think that this is genuinely going to be a masterpiece.

The broad editorial line is that we want to be publishing ambitious, imaginative, innovative contemporary literature, both fiction and nonfiction, that is engaged in some way with the world we live in. That’s obviously very broad, and I think that’s reflected in the diversity of our list. One of the ways by which we measure whether a new author is going to be a fit for us is by measuring their work against the people we already publish. Roberto Calasso, the legendary editor and writer, wrote in a book called The Art of the Publisher that for a literary publishing house every book is a singular work of art. But when you add up all of the books that a publishing house has published, the catalog as a whole is a work of art in and of itself. That’s something I read a few years in, and I think helped me and my colleagues put words to what we thought we were doing.

Another way of looking at it would be to think of a publisher’s catalog as a constellation where the books are all stars in the sky. There are connections between some of the authors, some of the books. We publish authors rather than books. I repeat this almost daily to the point of cliche, when we’re thinking about bringing a new author on. If the book that we happen to be considering has connections or echoes with other writers on the list, that tends to be a good thing rather than a bad one. Also, just to respond to the question of politics, we spend our entire day saying no. I reject books all the time. It’s the first thing you learn as a publisher, as an editor. And yes, there are things you reject outright because you know it’s not going to be interesting for political reasons.

Emre: Thinking about Daisy’s poem, I’m wondering if, for both of you, the translator always comes attached to the work. Or do you solicit multiple samples to figure out how to make a good match?

Levy: It’s entirely case dependent. As a matter of policy, when a translator brings us a book, we consider them as a package. We would never acquire the book and then jettison the translator. It just feels ethically uncool. But there have been some scenarios when we’ve commissioned samples. We don’t do it often enough to be aesthetically interesting, partly as a matter of practicality. I think every press has a stable of translators that they come to enjoy working with, their approaches to working on a particular author or text.

Emre: It’s rare to commission multiple samples and then choose.

Testard: Translators call this the beauty contest. And really hate it. They hate it.

Levy: We have done it, truly, fewer than five times, when we haven’t had a translator attached to a project at all. It might be a new language that we’re working in and are trying to get the lay of the land ourselves. In those cases, I have had a sense of how the text is working in the original, what kind of voice I’m expecting to hear on the page, and what kind of theoretical approach a translator is taking. The results can be vastly divergent.

In one case we had three samples come back. One really bristled us. It broke up sentences of the original in ways that felt antithetical, to me, as an approach to translation. I think it is the publisher’s duty to retain the aesthetic qualities of the syntax. It just felt really tonally off. Another one immediately brought so much life and energy to the English. It was so clear to me from this comparison of samples that the second translator was the one who would really do justice to the vision that we had for this author and this book.

Testard: We have done it once or twice, and it’s been at the request of the author. I prefer to avoid it. I think it’s unpleasant for everyone. I also think the translation sample itself is never going to be a reflection of what you end up publishing, because a translator is not going to go over that sample five or six times in the way that they might a full translation. You’re judging something that is not necessarily reflective of how good a translator can be. For a new author who doesn’t have a translator attached, we’ll often commission a sample from one person who we haven’t worked with before, just to get a sense of their work. We’ll sometimes do a test edit as well. I’ll send back notes on three-thousand words, just to show the translator how I work as an editor.

Emre: As editors, is there a difference between how you work on an original English-language text versus how you work on translations?

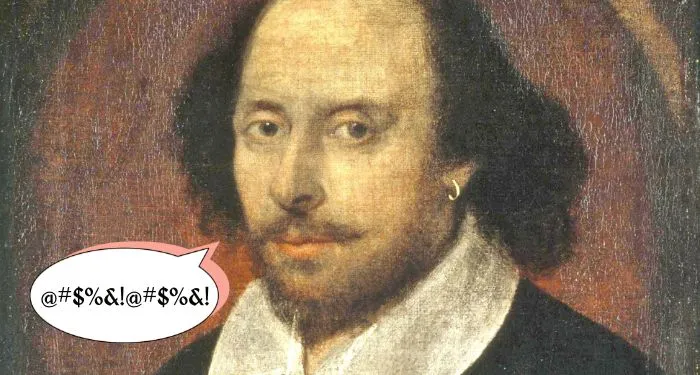

Testard: Not a fundamental difference. What you’re doing with the translation is limited because you’re essentially trying to help the translator write the best possible version of a book in English. It is line editing, to a point, but you do also have to question broader choices. To give you a concrete example, Hurricane Season by Fernando Melchor is an excellent novel set in Veracruz, Mexico. Sophie Hughes is a British translator. I am a British publisher. The book was going to be published by New Directions in America and by Text Publishing in Australia. We, on principle, tend to publish books in British English. But it felt weird for Sophie to be translating a book that was written in Veracruz in a slang that would be difficult even for someone from a Latin American country to read into British English. She ended up inventing a version of English, and—this speaks to what we discussed in a previous episode about increasing the capabilities of English—she landed on this transatlantic British English. There are some American aspects, there are some British aspects. My interventions as a line editor were mainly fine-tuning the swearing, of which there is a lot.

Emre: What do you mean by “fine-tuning the swearing?”

Testard: More “motherfucker” here, let’s say “ass” instead of “arse” because that sounds really weird in a Mexican context. And playing with the humor as well, which is a key part of the original.

Emre: Adam, do you have a different philosophy of editing translations?

Levy: No, I think our approach is pretty similar. For some of the authors that Jacques and I share, we have worked on alternate passes of the same translation. It’s been nice to see in certain cases the changes that he suggested and then the changes that I’ve suggested.

Emre: Has there been a situation in which you two have vehemently disagreed?

Levy: One really interesting case to me was when we jointly edited The Birthday Party by Laurent Mauvignier, translated by Daniel Levin-Becker. Jacques speaks French, and I don’t.

Daniel’s translation is superb. It’s a technically difficult book. There were definitely things in there that I didn’t flag because I wasn’t attentive to the French in the way that Jacques and the other editors at Fitzcarraldo were.

As someone who edits both English-language original works and translation, the approaches are very similar, but you’re coming in at a really different point in the writing process. The constraints are different. Obviously, when you’re working on an English-language original text, there’s so much at the developmental stage that is structural. We’re not getting involved with that kind of stuff when we’re editing a translation.

Usually, I’m trying to read to test the ground, see how sturdy it feels. When you can feel soft spots where the ground might give way, I’ll query the translator and ask, “What is the Spanish doing?” “What is the Japanese doing?” Oftentimes, it just starts a conversation, and sometimes it’s a relief. The translator will say, actually, this word or this sentence has really been giving me trouble. I haven’t been able to stick the landing here. Now I’m mixing my metaphors. People often think that editing a translation is like replacing one word for another. But it’s much more about trying to level the ground across the lines. More broadly, if this is early on in a translation or before the translation even takes place, editing can be at the level of the paragraph or at the level of the text as a unit. It can be just thinking, What, philosophically, is our approach to this? What are we going to do to smooth this? Can we rearrange the syntax or redo the syntax in such a way that we can take some pressure off of this one word that’s giving us trouble?

Testard: I think our process is not dissimilar. I tend to ask questions where the meaning is unclear, or where a sentence doesn’t feel like it’s flowing, or where I feel like I can offer an improvement either by rearranging something or moving the clauses around or suggesting other word choices. I might say, “This doesn’t quite work. How about this?” I might give a suggestion, and the translator is free to take it or not, or to do their own version of it. It’s very, very rare that I would go in and actually rewrite a sentence or make corrections with Track Changes. I would only do that if it’s to apply house style or if there’s an obvious typo or error. It is a very collaborative process. The role of the editor, and this goes for English language books as well, is essentially to ask questions. To make sure a reader is understanding the intention throughout a text, and to try and bring out the best possible version of it.

Emre: Maureen and Daisy have talked about when the author goes through the English translation and has either productive or unproductive quarrels with the translator. Have the two of you encountered that? How do you mediate those disputes?

Testard: It has happened. It can lead to some slightly difficult conversations with the translator, who might feel like they’re not being given the respect or freedom that they need. But I think more interesting is returning to the idea of English as the imperial language, and the pressure that is put on the English translation. This goes for authors all over the world. Sometimes they’ll be translated into English when we’re publishing them for the first time. It’s not just that they have a shot at winning prestigious prizes. It’s also that they will now become accessible to every single international editor who considers every work in translation through the language of English. We published Guadalupe Nettel’s Still Born, translated by Rosalind Harvey, before they were shortlisted for the International Booker Prize. I think the book was sold in maybe five or six territories. After the shortlisting, it jumped up to fifteen territories. That’s the impact a prize can have. If you win, maybe twenty-five. But the baseline of being in English is already hugely significant, especially if you’ve never been in English. I think that’s why there is this relationship that can become a little bit vexed with an author who speaks excellent English and who understands the pressures.

Levy: More often it’s the translator negotiating between editors or publishers and the author. We are working exclusively with the translators, and our relationship with the author is mediated by the author’s agent, the author’s publishing house. Sometimes we don’t even have direct contact with the author, and their wishes are expressed to us through a kind of confusing channel of publishing communications. Sometimes it’s messy.

Emre: I’m thinking about one of your authors, Mariana Dimopoulos, who is J.M. Coetzee’s Spanish-language translator. They have a lovely book that just came out called Speaking in Tongues. It’s an exchange about translation, and one of the things they talk about is how Mariana translated The Pole into the Spanish, which was published nine months prior to the English. They insisted that translators or publishing houses in other countries work off of the Spanish text, as opposed to the English. And you all might imagine how well that went, which is to say everybody refused to do it and wanted to wait for the English. What’s your response to their experiment?

Levy: I like the idea of subverting the traditional path of publication in a second language before the English, but I’m not sure that I can appreciate the translation experiment of translating out of a language that a novel has been translated into. A language that I have translated from is the Hungarian. It’s not Indo-European but is surrounded by Indo-European languages. In the past, Hungarian books have been translated into German and then into other languages, and that’s historically been the route of consecration for Hungarian authors. I think that it’s done a disservice to those authors. It’s smoothed out a lot of the idiosyncrasies, or just the stylistic particularities of those authors when they’ve taken this journey first into German and then into English.

Testard: The Dimopoulos-Coetzee experiment is a very interesting thing to try out. Politically, it feels like a significant thing to attempt. But the publishing industry worldwide is extremely conservative, and there was no way anyone was going to go for it, especially not with an author the stature of J.M. Coetzee, whose work all would have been translated from the English up until that point.

It reminds me of something that I heard this year when we published Sheila Heti’s latest book, Alphabetical Diaries, in February. It’s a book that she’d been writing for over a decade, an alphabetized edit of her diaries. The full text was something like 700 pages, and she edited it down to 55,000 words. It’s a book that has chance attached to it. By alphabetizing, you’re randomizing all the sentences in it. What she suggested to her foreign publishers was that they read and commission translations of the longer version—85,000 or 90,000 words, maybe the third edit—and then have the translator edit it down to roughly the length of the English-language edition. Obviously, everyone looked at her like she was insane. Well, they didn’t actually look at her. They just replied to her agent’s email by saying, “This is insane. We’re not going to do this.” I feel like that was in the same category: a conceptually or even politically subversive move in the realm of translation that doesn’t work given the time pressures, the market pressures, the ways in which people are making translation decisions. There’s no time for it.

Emre: There’s judgment at the acquisition stage, judgment at the editorial stage, and then there are the judgments of critics and prize juries. Jacques, you already pointed out that prizes can be extremely important for introducing writers into multiple territories and to many different kinds of readers. Jeremy, you chaired the National Book Award jury for translated fiction in 2023. How did you organize and instruct a jury tasked with judging among translations?

Testard: I think something that is understood by people in the industry, but maybe not necessarily by the general public, is that all of these awards are hugely subjective, and that a different jury on a different day might make a completely different choice.

Emre: I know we’re supposed to say that, but do you think that’s really true? That it’s purely subjective?

Testard: I don’t think it’s purely subjective. I think there is a certain level that you have to clear. The books have to be of a certain quality. They have to stand out from the crowd in one way or another. But once you’re left with the pool of, say, the top ten percent of books, then I think it really does come down to individual taste. If you look at the long lists, they are clearly indicative of different tastes or people looking for different things. I don’t think it’s that in this year all the books from Europe happened to be better. I think it’s more that this jury had more Eurocentric tastes.

Emre: How do you define a Eurocentric taste, other than simply a preference for books by people writing in European languages? Are there aesthetic qualities that you would associate with Eurocentric literature versus Southeast Asian?

Jeremy Tiang: I think Western European books in particular tend to adhere more to Anglophone ideas of narrative or structure. I have certainly been on juries when I’ve been the only person in the room working from an Asian language, and also the only person saying, Listen, I think we should really take a second look at this Vietnamese book. I feel like you’re all missing something, and let me tell you what I see in it. And sometimes you can talk a room around because even when people are considering each book with due attention and diligence, it is easy to let go of something because you haven’t taken that extra moment to try to see past the differences. It’s difficult because we can’t be completely objective, right? We’re all human beings with our individual tastes, and I think it’s much healthier to acknowledge that and to say this is not necessarily the best book that was published in this year. What would that even mean? But it is the book that this group of people liked the best—or, frankly, it was the book that people objected to the least, depending on the makeup of your jury.

Emre: In the National Book Awards, translated fiction is a very recent category, similar to how the International Booker came after the English-language Booker and was originally awarded as a lifetime achievement prize rather than a prize that was given for the book published in that year.

Testard: In an ideal world, we wouldn’t have a separate category for translated literature, which, as Adam points out, is not in fact a genre. Ideally, the translated books would just compete in the main Booker, translated novels would just compete in the National Book Award for Fiction. But these categories were set up as an acknowledgement of the parochialism of the Anglophone world, just like we have an “international” category at the Oscars. Then Parasite wins, and everyone’s like, “Wait, that’s not fair. They also won Best International Film!” Then Bong Joon Ho calls the Oscars a “very local” film award ceremony and generates outrage. But in fact, it is not truly international in any significant way, just as the International Booker is still focused on books translated into English. Of course, there are logistical reasons why it couldn’t truly be international. Ultimately, you can judge only the books that are published. If the publishing industry is not giving you enough books from, say, Africa, then Africa as a continent is severely underrepresented in the world of translated literature.

I think by acknowledging the imperfections in the system, we can give it less weight. It’s fun. Everyone loves a good party. Everyone likes to decide that we’re going to celebrate this book, but if we also acknowledge that there is a certain amount of subjectivity and arbitrariness to the selection, then it perhaps gives us a more honest view of this whole process.

Emre: Have you learned anything about the actual practice of translation from judging?

Testarfd: The primary thing I’ve learned is how Eurocentric the marketplace is and how overrepresented Western Europe is in the translation sphere, which I think is something I was aware of intuitively. But when you read all of the books and see how many of them come from particular countries and how underrepresented entire regions are, that really brings it home. It has made me more attentive to difference and more eager to have works that are translated from outside overrepresented areas carve out a space for themselves and their own idiom, rather than aspiring to the condition of assimilation.

Freely: I wanted to say something about the importance of panel formation or panel selection, because I have been on three translated literature panels. On one of these panels, we weren’t able to take anything from India because a lot of the interesting books that were coming out in India’s many languages weren’t technically being published in the UK. We used this as an opportunity. One of us made a big effort and said this was a problem, and that the organizers of the prize had to start doing something about it. I think panels can talk in the round about what’s missing.

Emre: Jacques and Adam have both talked about how the effort to affect the politics of translation on the production side is probably not going to work. But what both of you are saying, Jeremy and Maureen, is that effort could work on the consumption side. If you are the person chairing a jury or you’re on the panel, how do you think about using the prize?

Testard: I think the important thing to note is that literary quality is always going to come first, and we would never elevate a book that wasn’t as good just because it fulfilled a certain criterion of representation. What we can do is investigate our own biases. Are we elevating these books because they conform to the familiar? Are we overlooking certain books because they take a little extra work to get to know, because we haven’t read much from this place? I hope there aren’t many juries who would say, well, this book isn’t as good, but because it’s less represented let’s give it the award. I would hope rather that you create the conditions where publishers are perhaps more willing to look at the less familiar, but you do so without compromising on quality or aesthetic judgment.

Freely: There are also interesting discussions about the actual category of fiction. Ideas about fiction in the Anglophone world are really weird. The term “nonfiction” is a very strange term. So much of the really interesting writing coming out of Europe and other continents has been for several generations now troubling those categories. That conversation doesn’t seem to go very far in Anglophone literary discussions.

Tiange: I will say it’s quite exciting when you’re judging a fiction prize, and then you get a white Fitzcarraldo book, and you think, yes, smash that binary. It’s an artificial distinction.

Testard: I just wanted to pick up on what was said about the difficulty of affecting the politics of literary production. In the examples we were discussing, I think that is going to be very difficult but I absolutely do believe that it is possible to have that impact. The very simple way is by publishing books. Every act of publishing is political by necessity, particularly publishing translation into any language. But in our case, into English, it is a political act, and that’s how you have an impact on the culture, book by book, little by little, over the years. By trying to bring the diversity of world literature, for lack of a better term, into English.

I’ll talk a little bit about Eurocentrism, as the European in the room. When I started Fitzcarraldo, I was working on my own. I started with what I knew, which was, in my case, French literature, Spanish literature, Latin American literature. From there, slowly, the boundaries of what seemed possible for us to commission translations of and to publish expanded. A big turning point was the acquisition of Adania Shibli’s Minor Detail, translated by Elisabeth Jaquette, which was the first nonwestern language book that we published. That felt like something kind of new and risky to undertake, because we had no way to judge the source text. Really, we were relying on reports. Since then, we have made a conscious effort to look outside of Europe and have recently published Chinese authors like Dorothy Tse and Mieko Kanai from Japan, and we now have three Arab-language authors as well. You learn on the job.

Levy: This reminds me of an assignment that we give to prospective editorial employees. We give them, say, ten pages of an unmarked manuscript, with no indication of author, translator, anything, and ask them to offer an analysis of what they’ve read and what their recommendation would be for acquisition. We did this recently and the results were fascinating. Because our list is overwhelmingly literature in translation, most people assume that what we give them is a translated title. It totally informs the way that they read it, their analysis of it, and their recommendations. But the text we gave them was actually an Anglophone text written by a writer whose mother tongue was not English, but who wrote in English in the 1980s. A majority of people who were otherwise promising candidates picked the text apart at the level of syntax and style in a way that felt like their readings were overdetermined by the preconception that the work was written in another language and translated, and that the translation had problems. There were very few who allowed themselves to get taken away by a somewhat unusual syntax and style. Those were the candidates that we gravitated toward in our decision-making process. But I thought it was fascinating how the assumption that a text was translated completely informed the reading and evaluation of it.

Jewiss: I’m so struck by this example that you’ve just given, Adam. It brings me back to a question that we debated extensively when we founded the Margellos World Republic of Letters translation series at Yale Press. We were very insistent that the translator’s name should always be on the cover. In conversation with other presses, we were reminded again and again of how suspicious readers are of translations. I’m thrilled that we are honoring translators and putting names on covers, but I’d love to hear more about ways to break down or dissolve that suspicion. We began by talking about literary prizes, but the reader judges a translation through a whole series of filters that they wouldn’t use if they thought they were reading something that had been written originally in English.

Testard: We don’t put translators’ names on the front cover. We put them prominently on the back cover, and translators are named every time a book we publish is mentioned online, on social media, on Amazon, on a bookseller’s website. The book is prominently advertised as translated. I understand the reasons why translators’ names should be on the front cover, but I think it can be a red herring conversation. There are numerous publishers who do put translators’ names on front covers who don’t pay translators properly. A few years in, I was asked for the first time by a translator for a royalty payment, and we gave that translator a royalty. It’s been since 2018 or 2019 a policy that we pay translators a fee for the work that they do, and then they receive a royalty from the first copy sold on every print copy. I feel like it’s important to do that work first.

Emre: What do other people think about this division of material compensation versus recognition?

Tiang: It’s not an either/or. I commend you, Jacques, for paying your translators well, but you could do that and put our names on the front cover.

Testard: We have developed a commitment to the ethos of publishing authors rather than books. We have quite a few authors in translation who have different translators. Because we have this series design, where every book looks exactly the same, the authors become brands within the list as a whole. When you have different translators for different books, you’re not necessarily selling the translator. You’re selling the authors. But I can see looks of dissatisfaction.

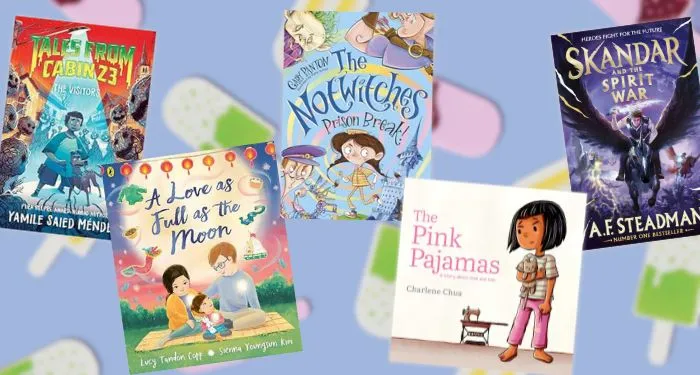

Tsao: I was reading my children The Never-Ending Story, which was translated from the German. When I read it as a kid, I had no idea. When I realized that it was a translation, I thought, “Oh my goodness, this has been a translation my whole life.” I really wanted to know that it was a translation. I was excited that this translator brought this work to me.

Levy: Especially with kids’ books, it’s not only that the books don’t have the names on the cover, but also that the publisher has retained the copyright and not granted the copyright to the translator. There’s really no evidence that the book has ever existed in another language.

Tiang: I do think it is important not just to foreground that a work is a translation, but also to foreground the translator as a figure. We were talking earlier about different renditions of a text, and I do want to know whose rendition I’m reading. You would never release a recording of a classical symphony without saying who the soloist was, who the orchestra was. We really do deserve to know what conduits the work has reached us through.

Levy: Now that we have a children’s book imprint and are learning more about the politics on that side of the industry. The most prominent international children’s book award, the Batchelder Award, has as one of its eligibility requirements that the translator have their name listed on the cover. I’m not trying to throw Jacques under the bus. He’s got his design.

Testard: I don’t feel thrown under the bus, really, because it’s really obvious when we publish a work in translation that it is a translation. It would be really hard for anyone to argue that it isn’t. I’m at peace with myself.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·