Erica Ezeifedi, Associate Editor, is a transplant from Nashville, TN that has settled in the North East. In addition to being a writer, she has worked as a victim advocate and in public libraries, where she has focused on creating safe spaces for queer teens, mentorship, and providing test prep instruction free to students. Outside of work, much of her free time is spent looking for her next great read and planning her next snack.

Find her on Twitter at @Erica_Eze_.

I saw a TikTok recently (I know, but hear me out) that talked about the theory of physical environments shaping languages. In it, @danniesbrain explained how more tropical and warmer climates tended to have more tone-dependent and vowel-filled language, while colder climates have consonants, which require less precise vocalizations.

There is also the very real effect that people have on their environments, which can be seen explicitly and tragically in how the genocide of America’s Indigenous populations resulted in climate change that is still felt today. This was because, like all Indigenous people, the people of the Americas had grown and learned with their physical environments — and the resulting ecosystem became dependent on them just as they’d become dependent on it.

The relationship between people and place is one that I feel doesn’t get enough consideration in more Eurocentric cultures, but it is nonetheless, something I can’t help but think about as American. Lately, I’ve found myself thinking specifically about how things like the architecture, the music, and even the accents would be different if Europeans hadn’t brought their dusty antics over here. Turns out, even how we weather storms would be different. One example of this is the recent devastation we’ve experienced because of weather, and how mangroves, whose populations are crucially aided by Indigenous communities, might have mitigated the effects of the storms.

This Native American Heritage Month, dive with me into books that show us the legacy of the people who shaped this land before us.

The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World by Robin Wall Kimmerer, illustrated by John Burgoyne

Acclaimed Indigenous scientist and writer Robin Wall Kimmerer shows exactly what I was talking about when it comes to Indigenous people and their relationship with their land. Here, she considers the gift economy and how we can better position ourselves when it comes to reciprocity and community, based on lessons from nature. Which is, of course, in direct contrast to the capitalist-driven culture of scarcity we currently live in.

I Was a Teenage Slasher by Stephen Graham Jones

Graham Jones stays doing the damn thing when it comes to horror that centers Indigenous stories. In his latest, it’s 1989 in the small, oil and cotton-driven town of Lamesa, Texas, and Tolly is a senior in high school who is about to “be cursed to kill for revenge.”

Indian Burial Ground by Nick Medina

Noemi Broussard is all set for a change when her boyfriend dies by suicide, and whatever progress she made gets upended. But there’s something about the details of Roddy’s death that just doesn’t make sense. Then, her Uncle Louie returns to the reservation, and with him comes some key clues to figuring out what really happened to Roddy. But there’s something else he brings, too — a horror that Noemi may regret knowing.

Wandering Stars by Tommy Orange

This follow up to Orange’s breakout hit There There is part prequel and sequel. Going all the way back to Colorado in 1864, it shows the legacy of the United States’ routine destruction of Indigenous lives and culture. Star, a survivor of the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre, has his history forced out of him by evangelical prison guard Richard Henry Pratt, who later founded the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. Later, Star’s son Charles is sent to this Indian school where he is tortured by Pratt. It’s also where he meets fellow student Opal Viola, with whom he shares a bright vision of the future. Fast forward to Oakland, California in 2018, and Opal Viola Victoria Bear Shield is trying her best to keep her family together after the tragedy that happened in There There.

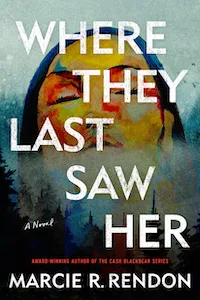

Where They Last Saw Her by Marcie R. Rendon

Quill is no longer the lonely Native girl she was when she grew up on the Red Pine reservation in Minnesota. She is still living there, but now, after a lifetime of seeing what happens to women and girls who look like her, she’s had enough. That’s why, when she hears a scream while she’s out training to run the Boston Marathon one day, she starts investigating with only tire tracks and a beaded earring to go off of. As she searches, someone else goes missing, and she’ll find herself needing all the support of her husband, friends, and community to confront the dangers her people face.

Whiskey Tender by Deborah Jackson Taffa

Growing up in the ’70s and ’80s, Taffa spent time on both the California Yuma reservation and the Navajo territory in New Mexico and was encouraged to “transcend” her Indian status through education. But, as she gets older, she begins to question how her people’s history and culture were systematically destroyed — whether by the Indian boarding schools her grandparents were sent to, or by the off-reservation governmental job training her parents were encouraged to do.

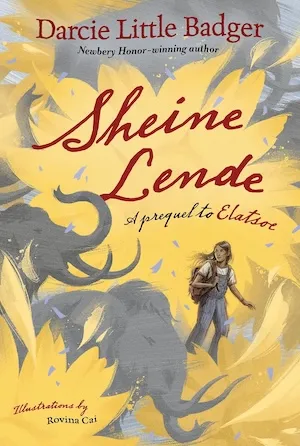

Sheine Lende by Darcie Little Badger, illustrated by Rovina Cai

I have sung the praises of Little Badger’s fabulism YA debut, Elatsoe, and love that there’s another story set in the mostly familiar world. Sheine Lende takes things back a bit, though, as this follows the first book’s grandmother, Shane, who is a teenager. Shane and her mother have the same skill Elatsoe had — they can summon the ghosts of animals — which they use to find missing people. But then one day, Shane’s mother and a boy from the neighborhood go missing, so she gathers a squad to help her. But not everyone in her crew is exactly trustworthy, and the journey to find the missing people takes them to places — and times — they never would have imagined.

*All-Access Members Can Continue Below for Must-Read BIPOC Releases Coming Out This Week*

English (US) ·

English (US) ·