According to the historian Sunil Amrith, who grew up in Singapore in the 1980s, his home country is “as committed as anywhere on the planet to remaking nature for human ends.” In The Burning Earth, his insightful survey of the long human struggle to escape environmental limitations, Singapore serves as a microcosm. Since the island nation’s split from Malaysia in the 1960s, civil engineers have increased its land area by 25 percent, using sand dredged from riverbeds all over Southeast Asia to expand its margins. Per capita GDP increased by one hundredfold during its first five decades of independence, a success that the republic’s first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, credited to the transformation of its indoor climate: “Air conditioning was a most important invention for us, perhaps one of the signal inventions of history,” he said in 2009. “It changed the nature of civilization by making development possible in the tropics. Without air conditioning, you can work only in the cool early-morning hours or at dusk.”

Amrith, a professor of history at Yale, was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in 2017. Born in Kenya to Indian parents, he spent much of his childhood in the shopping malls and movie theaters of Singapore’s artificially temperate and increasingly vertical city, paying little attention to the tropical world around him. As a historian, he was initially interested in political and social mobility in Asia, publishing a study of the region’s migration patterns. In two subesquent books, Crossing the Bay of Bengal (2013) and Unruly Waters (2018), he examined migration as a persistent attempt to overcome geography and climate.

In The Burning Earth, Amrith radically expands that project, considering not only migration but much of human history as a battle against planetary forces. During a 2012 trip to Bangkok, he walked the banks of the Chao Phraya, Thailand’s primary river. It had flooded catastrophically after heavy rains the previous year, killing hundreds of people and affecting 13.6 million; the World Bank estimated that it was among the costliest disasters in world history. By the time Amrith visited, the river had once again opened to traffic, and he watched as barges loaded with sand from Cambodia and Myanmar motored toward construction sites upstream. “The scars of the recent floods were confined to private grief,” he writes. “The life of this great city went on.” But as he considered the region’s recent procession of climate-fueled disasters—the monsoon-season flooding of Mumbai in 2005, the leveling of Yangon by Cyclone Nargis in 2008—he began to wonder whether its apparent resilience was instead a kind of blindness.

Many environmental histories, especially those of global scope, are stories of ruination wrought by human greed. While Amrith pays due attention to that greed, he is more interested in the delusion, chronic in the most privileged among us, that “true human autonomy” can be achieved only through “a liberation from the binding constraints of nature.” The Burning Earth lays less blame on our worst instincts than on a blinkered version of our best, tracing a hubristic “quest for freedom” that began in the era of Kublai Khan and continues in the era of Elon Musk.

As a history, The Burning Earth is unconventional in ways that help and occasionally hinder its argument. Though Amrith’s poetic language beautifully emphasizes the epic scope of his story, it can also be frustratingly oblique, in some cases leaving the reader unsure which kind or kinds of “freedom” he is referring to. Here the taxonomy proposed by the historian Timothy Snyder in his new book On Freedom1 may provide some clarity. Snyder enumerates five forms, including sovereignty, which he defines as one’s capacity to make choices; unpredictability, the ability to act according to one’s own values and changing circumstances; and mobility, the ability to move not only through space and time but within society. His two remaining forms are factuality, which he describes as a shared understanding of reality—“what life is; how life works; how life is possible on this earth”—and solidarity, the recognition that freedom is a collective state. Throughout The Burning Earth, elites pursue individual sovereignty, unpredictability, and mobility at the expense of societies’ factuality and solidarity.

Amrith begins in medieval Asia as the Mongols, who had built a steppeland empire on horses and grass, expanded beyond their ecological niche and invaded southern China. The Mongols were largely unimpressed by the rice paddies so carefully cultivated by the Chinese, but rice, domesticated thousands of years earlier and planted all across the region beginning in the tenth century, had more than doubled China’s population. When Kublai Khan established the Yuan Dynasty in 1271, he recognized the power afforded by the transformation of pasture into paddies and broke with fellow Mongols, including his younger brother and rival Arigh Boke, to encourage the continued growth of agriculture.

In Europe, meanwhile, farmers and their lords were turning forests and marshes into wheat fields, fueling a near tripling of the population between 800 and 1300. As the Mongol Empire reopened trade routes between Europe and Asia during the thirteenth century, precious and novel goods—jewels, spices, medicines, paper, flora and fauna—were exchanged by land and sea. People and things were more mobile than ever before, giving the wealthy access to an almost unimaginable range of possessions and ideas.

Early in the fourteenth century, however, catastrophes struck. Several hundred years of unusually warm, wet weather came to a sudden end; superstorms in both Europe and Asia flooded fields and killed livestock, and millions of people died. Most devastating of all was Yersina pestis, the bacteria that causes plague, which traveled from Central Asia to Western Europe on the flourishing trade routes. The monumental toll of the Black Death exceeded that of the Covid pandemic by severalfold: it killed between 75 and 200 million people across Eurasia, including an estimated 30 to 60 percent of the population of Europe and the Middle East.

“As the plague moved through western Eurasia,” Amrith writes, “it squeezed the thin margin of security hard won by those who had cleared land and planted new crops.” He quotes the Italian humanist Petrarch, who wrote at the time, “Our former hopes have been buried with our friends.”

How transient and arrogant an animal is man! How shallow the foundations on which he rears his towers!… Go, mortals, sweat, pant, toil, range the lands and seas to pile up riches you cannot keep; glory that will not last.

Rich and poor had been felled by what appeared to be nature’s whims, and around the world, Amrith writes, “states and societies consciously widened their margins of safety.” Europeans, hemmed in by hostile forces on land, began to seek security and wealth overseas, establishing fortified settlements on Atlantic islands and the African coast in the early 1400s and then, at the end of the century, crossing the Atlantic to North America.

As Amrith emphasizes, European abuse of the Americas was not the only world-shaping event of the time. Between the mid-1500s and the early 1700s, the Russian Empire expanded its territory by more than fivefold; migrants eager for security or wealth or both cut down forests, replaced grasslands with rye and wheat, and seized and sold foxes and beavers by the wagonload, dispossessing nomadic peoples from Northern Europe to the Pacific Ocean. India’s Mughal rulers organized settlers to turn Bengal’s forests into rice paddies; imperial China reached the edge of the Russian Empire.

The colonization of the Americas, however, was uniquely consequential, decimating the societies and agricultural practices of North and South America while simultaneously exploiting the blood and toil of enslaved people from West Africa. The profits flowed to European investors, then spread worldwide. Amrith traces the ripple effects: silver from Spanish mines in the Andes, extracted at appalling cost by enslaved and conscripted workers, was exported to China, where it was more valuable than in Europe. At least as valuable to the Chinese, however, were the American crops also carried by the trading ships. Sweet potatoes, more nutritious than rice and far less labor-intensive, arrived in China in the late 1500s and became a staple, rescuing millions from war- and weather-induced food shortages. Armies fed by the caloric windfall enabled the expansion of the empire, and the elite’s bloody pursuit of their interests continued.

All of these upheavals were funded by forests. The trees cut to make way for agriculture also provided fuel for cooking, heat for survival, and lumber for the ships that carried riches, disease, and the enslaved across the oceans. But in the 1800s much of the world turned to a more concentrated form of energy. “Industrial flames devoured the crushed remains of ancient forests and all the life they had once contained—amphibians and early reptiles and enormous insects,” Amrith writes. “Old life, shaped into a form of rock that we call coal.”

The effort to remake the planet to human ends became supercharged. With widespread access to fossil fuels, Amrith points out,

human productive power was decoupled from the growth cycles of timber, from the seasonality of rainfall and river flow. It was suddenly possible to imagine the unimaginable: freedom from wind, water, and earth.

As cities filled with choking smoke—visible, palpable evidence of coal’s cost to the environment and the less privileged—the implicit bargain of the preceding several centuries became explicit: “that the degradation and sacrifice of nature is the necessary price of a human freedom from want.” That such freedom was far from universal remained largely unsaid.

Wisely, Amrith sometimes slows his narrative to consider an individual, and he takes time to follow Albert Kahn, who arrived in Paris as a penniless teenager in 1876 and, beginning as a clerk in the Goudchaux banking house, speculated so successfully in the diamond mines in South Africa that by the end of the century he was among the wealthiest men in Europe. Even as Kahn and men like him profited from the inhuman conditions in the world’s mines and oil fields, he worried about the pace of change and sought to document the full spectrum of its effects. He eventually created the Archives de la Planète, which between 1909 and 1931 sent photographers to fifty countries and produced 72,000 images, capturing peat diggers and weavers as well as railways and dams. Amrith describes it as a visionary but deeply fraught project—a testament to the costs of industrialization, underwritten by the extraction of diamonds and gold—and until early in this century, it was largely inaccessible to the public. Its lofty perspective was reserved for those who had already reached great heights.

As Kahn’s photographers were cataloging the effects of the first industrial revolution, a second was mobilizing the power of chemistry. Synthetic nitrogen, invented in the early 1900s to free humanity from fertilizer shortages, was quickly repurposed for battlefield explosives in World War I; chlorine gas, phosgene, and mustard gas, weaponized first by German forces and then by Allied powers, killed tens of thousands of soldiers and maimed more than a million. At the same time, fossil fuels powered trucks, planes, submarines, and the new armored vehicles called tanks, opening new fields of battle and enabling new levels of destruction.

The horrors of World War I led many to question humanity’s continued pursuit of technological power. One of Amrith’s most striking anecdotes is an account of a 1931 meeting between Charlie Chaplin and Mahatma Gandhi, during which Chaplin asked about Gandhi’s “abhorrence of machinery.” Many supporters of Indian independence believed that industrialization would allow them to escape colonial rule, but Gandhi did not share their enthusiasm. “God forbid that India should ever take to industrialization in the manner of the West,” he had recently written, for “if an entire nation of 300 million took to similar economic exploitation, it would strip the world bare like locusts.” Five years after meeting Gandhi in London, Chaplin released Modern Times, his classic parody—and indictment—of the factory assembly line.

Such warnings, always in the minority, were drowned out by the roar of World War II, a conflict driven in part by Nazi fear of ecological limits and partly determined by the agricultural and industrial dominance of the United States, which supplied the Allies with crucial food, machinery, and fossil fuels. The same industrial capacity enabled the development of the atomic bomb, which US pilots unleashed on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. Contemplating the terrible, far-reaching consequences of the war and the nuclear attack, Amrith describes them as “the dark culmination of a century-long history that saw the twinned acceleration of both human and environmental destruction.”

And yet. As Amrith’s history moves into the second half of the twentieth century, a reality present throughout his narrative moves to the forefront: although the drive for freedom from wind, water, and earth has delivered great wealth to a few and great suffering to many, it has also brought wider benefits. Improvements in diet and advances in medicine and sanitation over the centuries mean that, on average, we live dramatically longer lives than our ancestors. In 1800 fewer than half of the world’s people survived to adulthood; by 1900 life expectancy in most of Europe was between forty-six and forty-eight years. Over the late twentieth century and early twenty-first, life expectancy in most of the Global South doubled, narrowing the gap between wealthy countries and the rest of the world. Amrith notes that in no country today are rates of infant mortality as high as they were in Britain in 1900. We still fear pandemics, and for good reason, but Yersina pestis can be treated with antibiotics.

To explore this conundrum, Amrith turns to the work of Hannah Arendt, Rachel Carson, and Indira Gandhi. Arendt, who blamed industrial capitalism for the violent imperialism of the late 1800s and the Nazi and Stalinist terrors of the twentieth century, mostly ignored the benefits of technological progress for ordinary people and condemned early experiments in spaceflight as a “rebellion against human existence as it has been given.” Carson, often unfairly caricatured as an absolutist for exposing the very real ecological dangers of the pesticide DDT, may have nonetheless underestimated its value as a malaria-fighting tool. Only Indian prime minister Gandhi, in her address to the 1972 United Nations Environment Conference in Stockholm, prominently acknowledged the challenge—and necessity—of living within our earthly means while ensuring that all enjoy technology’s most basic benefits. “We cannot for a moment forget the grim poverty of large numbers of people,” she told the conference. In Snyder’s formulation, she was calling for both factuality and solidarity—a shared understanding of reality and a recognition that freedom is a collective state.

Gandhi later ignored her own advice, declaring a national state of emergency in 1975 that led to a brutal mass-sterilization campaign against the poor. But while Amrith’s story is, on the whole, a tragedy, he finds the beginnings of another story in the activists who took up Indira Gandhi’s challenge, risking—and sometimes sacrificing—their lives to fight deforestation in Brazil, mega-dam construction in India, and the abuses of the oil industry in the Niger Delta.2 As the effects of climate change advance, this “environmentalism of the poor,” with its understanding of planetary limits and its commitment to the common good, is becoming the environmentalism of us all.

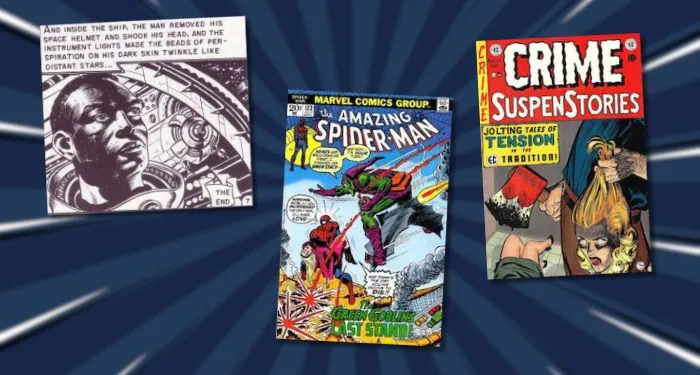

The Burning Earth frequently and effectively turns to writers and artists as observers of their times, relying on them to see more clearly than their contemporaries. Anton Chekhov, in his reporting from the early 1890s, sympathized with those who migrated to new Russian territories in hopes of a better life; Akira Kurosawa, in his 1952 film Ikiru (inspired by Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich), captured the despair of postwar Japan; Hayao Miyazaki, in his 1997 film Princess Mononoke, cautioned that in the war against humanity’s habitat, there is no victory.

The Burning Earth brought to mind another work of art: the poem “High Flight,” by the World War II combat pilot John Gillespie Magee Jr. “I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth/And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings,” begin the verses he sent to his parents in September 1941. Magee died in a midair collision just three months later. His words have survived endless repetition; in 1986 they were invoked by Ronald Reagan in a tribute to the seven astronauts killed in the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger. Whether the casting off of planetary bonds is literal or figurative, the prospect is delicious, and as Amrith so convincingly shows, it has animated the powerful for more than a thousand years. Yet the costs of the attempt are steep, and they are ever harder to escape.

Amid the “powers of human and more-than-human destruction” loosed by World War II, Amrith writes, “the possibility of life, of survival and renewal, lay in cultivating the ruins of nature by the sides of ditches and in straggly blotches of green among shattered cityscapes.” Christopher Brown, the author of A Natural History of Empty Lots, lives far from any conventional battlefield, but he is surrounded by the wreckage of a different war, and he, too, finds hope in cultivating the ruins of nature.

In 2009, in the midst of the financial crisis, Brown was recently divorced, co-parenting his young son, and pursuing dual careers as an attorney and science fiction novelist. While searching for a house he could afford in Austin, Texas, he happened upon an old industrial site along the Colorado River—a former “tank farm” where Chevron and other companies had stored fuel until community advocates exposed the site’s chronic air and water pollution. One lot was bisected by an old pipeline, strewn with huge slabs of concrete, and hidden behind a chain-link fence. He was persuaded by the low price and a certain romanticism—as a sci-fi writer, he suspected that “nothing would be cooler than to live in an overgrown concrete bunker that looks like the last outpost after the end of the world”—to buy the lot and have the pipeline removed. In the years since, he has made the place his home.

A Natural History of Empty Lots, composed of short essays about Brown’s deepening relationship with that place, is a work of nature writing about an industrial landscape. He adapts the term “edgelands,” coined by the English ecologist Marion Shoard, to describe the urban spaces he comes to see as hidden wildernesses—“topographies we can never really occupy, even as we encroach as closely as we can.” These places are deeply scarred by human ambition, but Brown finds that they can be full of life, and he admires the resourcefulness of the foxes, hawks, ants, coyotes, and many other species that share his habitat. He writes:

The experience of such spots can help us better understand our own nature, learn to see the ways in which the institutions of our civilization distort that nature and make us its indentured servants, and begin to imagine a future that better balances green life with human control. More simply, we can help realize the promise of edgelands’ emptiness, encouraging vacant lots to grow into pocket parks and miniature forests, as is beginning to happen in cities around the world. In a world where hope seems endangered, the kernels of its rekindling can be found in what we have long treated as its most hopeless corners.

Brown hired two young architects to design a house that reflected the landscape, and the oddly beautiful result looks something like a fallen space capsule, half submerged in the deep trough left by the excavation of the pipeline. The angled concrete slabs that form its roof are planted with native prairie species that now drape over the eaves, a living reminder that this structure, too, will likely go to ruin.

A Natural History of Empty Lots is less a departure from the nature writing tradition than a welcome addition to its edgelands. Like the filmmaker Derek Jarman in Modern Nature (1991), his book about tending a seaside garden in the shadow of the Dungeness nuclear power stations in southeast England, Brown avoids the nostalgia so prevalent in the genre. While he mourns the damage done to the place he comes to love, he lingers instead on the odd marvels of the present: an abandoned cardinal nest woven from cellophane and pharmacy receipts, rich honey made by invasive bees living in a half-buried tire, escaped parakeets in the cell phone towers. And though his family’s ongoing project is a kind of restoration, they are less interested in imitating the past than in sharing their refuge with coyotes and armadillos, butterflies and carpenter ants, hackberries and wild peppers—as Brown writes, “dreaming the feral city, and making it real.”

Brown’s home sits a few miles upriver from Tesla Motors’ 2,500-acre Gigafactory, completed in 2022 after Tesla’s CEO, Elon Musk, promised to turn the nearby riparian zone into an “ecological paradise.” (He has done nothing of the sort.) Musk, with his cartoonish visions of a “multiplanetary society,” is still touting the dream of earthly escape, a future in which the wealthiest can leave the consequences of their actions millions of miles behind. Brown and others like him—all those repairing landscapes large and small—have seen this vision for what it is, and found that within the ruins of runaway human ambition, they can attain a more egalitarian kind of freedom.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·