The more closely one contemplates the life—or lives—of Sir Roger Casement, the more of a cipher he becomes. The very endeavor to fix his image seems somehow to leach the pigmentation from it, until all that is left is a spectral shimmer. Like T.S. Eliot’s Macavity the Mystery Cat, whenever and wherever one looks for him, Casement is not there.

This insubstantiality is all the more marked, and remarkable, for the fact that Casement was one of the most prominent public figures in British and Anglo-Irish life at the turn of the twentieth century, internationally celebrated and more than once decorated for his work in exposing the horrors that indigenous peoples in the Belgian Congo and the Putumayo region of South America were suffering at the hands of their white masters in the increasingly lucrative rubber trade. He was, of course, a man divided, in soul and in body. As his biographer Roland Philipps writes in Broken Archangel, “Casement’s foundations were insecure, shadowy and shrouded in secrets.”

Born in Sandycove, on the south side of Dublin, in 1864, he was brought up in the far northeast of the province of Ulster, six counties of which were later partitioned off to become the separate and much fought-over state of Northern Ireland. Although he became, or goaded himself into being, an extreme Irish nationalist, he spoke, dressed, and comported himself with the dignity and refinement of an English gentleman. In fact, it would be hard to find a more convincing example of that largely mythical breed. Yet he would have objected violently to such a characterization, especially in the later years of his life, when his devotion to Ireland and all things Irish intensified to almost demented levels.

The Anglo-Irish gentry were never, and for the most part did not try to be, fully accepted by the native Irish, although lawyers, doctors, and businessmen of the Catholic middle class were always more than happy to supply their services to the well-heeled “Horse Protestants” grazing peaceably among them. Casement’s father, also called Roger, was the son of a well-to-do Ulster shipowner who went bankrupt after the loss at sea of a series of grain transports from Australia. Roger senior joined the British Army and served in India for a time before retiring early on half-pay, for reasons unknown to history.

He married Anne Jephson, who was also descended from an Ascendancy family—or so she claimed; Philipps and others suggest that she may have been born out of wedlock, as the genteel formulation had it. She does seem to have come from Catholic stock—it would have been on her mother’s side—for she was said to have had her son secretly baptized into the Roman Catholic faith when he was four years old.

Anne Casement had eleven pregnancies, but only four children survived. Of Roger’s siblings his favorite was his sister Nina, eight years older than he. She was one of the numerous loyal and strong-willed women who supported him throughout his life, celebrating his achievements, forgiving his failings, and, at the end, tirelessly petitioning for him to be spared the gallows.

Roger senior had sangfroid to spare, along with a taste for derring-do and a fondness for the histrionic gesture. As the Irish like to say, he did not beg, borrow, or steal these traits. At the end of the 1840s the Hungarian leader Lajos Kossuth and his followers were engaged in a struggle to free their country from Austrian rule. Close to defeat and trapped with his army between Austrian and Turkish forces, Kossuth decided to plead with the British government for help. Suddenly, and seemingly out of the blue, there appeared Captain Roger Casement of the 3rd Light Dragoons, stationed in India, offering to act as emissary to the British foreign secretary, Lord Palmerston.

Kossuth immediately wrote a letter, which Captain Casement carried all the way across Europe on horseback and personally delivered into Palmerston’s hands, interrupting the statesman at his dinner. Palmerston took immediate action, the British Army intervened, and Kossuth and his men were saved. Although Philipps does not mention the quaint circumstance, it is elsewhere reported that when Casement popped up at the Hungarian camp he was sporting a top hat and twirling a furled umbrella. The shine soon faded, however. As Philipps drily notes, “Nothing else in the elder Roger’s life contained even a hint of the glamour of his dash across Europe.” But his son surely recalled the glory that had been. In the early stages of their life together Casement’s parents were possessed of a certain élan, even if they were not much good in day-to-day matters:

The tall, striking couple and their growing band of children…led a peripatetic existence, moving between the Isle of Man, Boulogne, possibly Italy, Jersey (where young Roger became hooked on swimming, according to his sister) and Dalston, Surbiton and Dorking on the outskirts of London.

It was a precarious existence, with Roger senior making frequent appeals for monetary assistance from his relatives in Ireland and issuing hypochondriacal bulletins on his supposedly chronic ill health, “from which death would be a merciful release.” Most of his moaning fell on deaf ears—one of his relatives described him as “an insinuating idler who lived on his debts.”

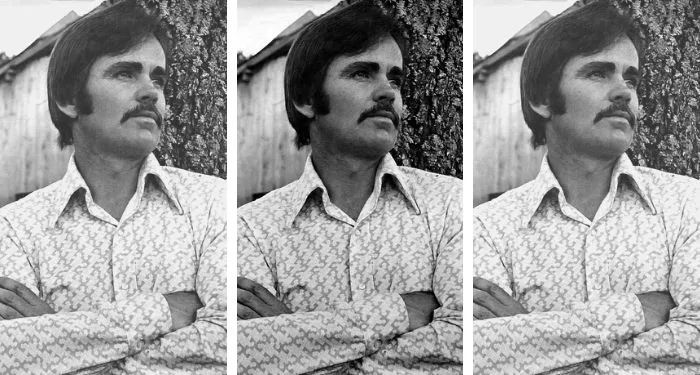

Along with his genetic inheritance, this cosmopolitan, or at least roving, upbringing must account for Roger junior’s front of sophistication and his self-assured deportment, helped by the fact that, as photographs attest, he was surely one of the handsomest men of the age. Behind the mask of beauty, however, there was hidden a secret emotional and sexual self. The temptation to cast him as one of Oscar Wilde’s exquisite but doomed protagonists is irresistible.

When he was nine his mother died, in childbirth, so the boy believed, although her death certificate indicated that she had been suffering from cirrhosis of the liver. Philipps perceptively writes:

She died apart from her family shortly before her fortieth birthday in a boarding house in Worthing, and her alcoholic absences, both emotional and actual, would be a critical factor in her son’s make-up: his inability to regulate and override his emotional responses as a result of the lack of guidance in early years was one of his campaigning strengths, but also a significant catalyst in the tragedy of his last years.

Throughout his life the son remained devoted to his mother’s memory and, according to his cousin Gertrude Bannister, “constantly spoke of [her] gentleness, beauty, bright disposition and religious feeling.” It is one of Casement’s many admirable qualities that he always endeavored to think and speak in the highest and fondest terms of the people around him—though should one of them let him down or turn against him, he was implacable in his anger and reprehension. How ironic it is that he failed to recognize the young man who was his last love as the heartless betrayer he proved to be.

Roger Casement senior died when his son was twelve years old. Already young Roger had endured “a disjointed and bewildering childhood,” Philipps writes, “that left him emotionally hollow and with a carapace of withdrawn self-sufficiency.” The boy became the ward jointly of his great-uncle, John Casement, and John’s daughter Katie Pottinger, and when not at boarding school he lived at one or another of their houses.

Happily, his natural flair was not subjected to the blurring effects of overeducation. He left school at fifteen and was never a great reader, except of nationalist tracts and Celtic Twilight kitsch. He received middling class reports, being good at history and geography but not arithmetic. He developed a love for the English poets and for Irish history and legend, though he did not master the Irish language, a lack that was to trouble him all his life. While the poetry he wrote was mostly dewy-eyed, pietistic doggerel, his prose, except when he was aggrieved or angry or both, was stylish, subtle, muscular, and direct. At the end, when all his hopes and aims lay in ruins, he still spoke and wrote with selfless nobility.

Having left school, the orphan went to live with his “wee auntie” Grace Bannister in Liverpool, “the only stable home in Casement’s life,” according to his biographer. There he became close to Grace’s daughter Gertrude, who in later years was to be “the loyal protector of his reputation as a man of ‘gentleness and tender-heartedness,’” Philipps writes. Aunt Grace’s husband was an agent for the Elder Dempster shipping company, and it was through this connection that Roger got his first job, as a clerk. It was a lowly beginning for a man who would rise to “greatness, worldwide acclaim”—and the scaffold.

He was a restless youth and quickly took himself off to sea. He was nineteen when he arrived for the first time in Boma, on the Congo River some sixty miles inland from the Atlantic coast. Already the “Scramble for Africa” was well underway, as European nations competed for riches and power in the so-called Dark Continent. Prominent among the scramblers was Leopold II, King of the Belgians, one of history’s shrewdest and most ruthlessly acquisitive monarchs, whose genius, Philipps writes, was to understand that “any territory belonging to tiny Belgium had to be presented as a largely humanitarian venture.” For years he got away with the pretense that his interest in the fabulously wealthy territories of the Congo was charitably motivated. Instead he turned the Congo into his personal fiefdom, earning millions for himself by trading in palm oil, copper, ivory, and, most lucratively, rubber.

In 1885, at an international conference on the future of Africa, the mention of Leopold’s name brought the delegates to their feet cheering:

He became King-Sovereign of the Congo Free State on 1 June, ruler of a territory that encompassed a thirteenth of the entire African land mass, was larger than Western Europe and seventy-six times the size of Belgium. Bismarck declared that the state was “destined to be one of the most important executors of the [humanitarian] work we intend to do” and hoped for the speedy “realisation of the noble aspirations of its illustrious creator.”

In fact, the Congo became a hell on earth for its indigenous peoples, countless thousands of whom were compelled to slave for Leopold and his savage administrators in the pursuit of more and more natural resources, especially rubber. Far from the benign ruler he pretended to be, Leopold was as cruel and rapacious as any of history’s monstrous despots. As to his “noble aspirations,” one of his subordinates, quoted by Philipps, put the royal view succinctly: “There is no question of granting the slightest political power to negroes. That would be absurd.” Far from giving them anything, Leopold’s enforcers took everything from the Congolese people, including, in many cases, their hands: the cutting off of limbs was one of the most prevalent forms of punishment inflicted on workers who underachieved.

After three round trips from Liverpool to Africa on the cargo ship the SS Bonny, Casement opted to settle in the Congo. To call it a fateful decision would be an understatement. It could be said that not Ireland but Africa was the moral making of Roger Casement.

He worked a number of jobs in the Congo Free State and joined the International African Association, run, as a front for depredations, by Henry Morton Stanley, the explorer, journalist, soldier, and unmitigated scoundrel who boasted that in the course of a yearlong exploratory journey through central Africa he and his men had “attacked and destroyed 28 large towns and three or four score villages.”

At first Casement accepted the rough and tumble of Congolese life, but soon he came to see—as did his friend for a brief period at the time, Joseph Conrad—the horror that lay at the heart of colonialism. In 1888, only three years after his lavish endorsement by the Berlin Conference, Leopold set up the Force Publique, which Philipps describes as “a grim hybrid of a violent military police unit, a mobile guerrilla force and Leopold’s private army.” The treatment by this gang, and other “officials,” of native workers—slaves in all but name—makes for hardly bearable reading. In Leopold’s Congo Free State the white overlords were given absolute power over the indigenous peoples—and we know all too well what human beings are capable of in such circumstances.

In 1901 Casement joined the British Foreign Office and became consul at Boma. In this position he was commissioned to study conditions throughout the vast territory of the Congo Free State. He traveled extensively in the interior for ten grueling weeks and afterward recorded what he had witnessed in a long, detailed, and carefully considered report to the British government. When it was published as an official white paper in February 1904, Casement was enraged to find that the identity of “agents and locations, tribes and individuals” had been redacted, which in his inflamed opinion meant “the report will cease to be a faithful record” and instead would be “absolute fiction and worthless.”

This was his first but by no means last lesson in the inadequacy and evasiveness of those in positions of power. The Foreign Office staff he described as “a wretched set of incompetent noodles,” though he reserved his real fury for Sir Constantine Phipps, the British minister in Brussels, for whom Leopold could do no wrong. Casement described Phipps as a “cur” and “beneath contempt” and wished he could set about him “with a good thick Irish blackthorn.”

All the same, the Casement Report, as it came to be called, did have an effect. A Congo Reform Association was set up, and a number of countries, including the United States, demanded action. Eventually Leopold was forced to order an independent inquiry, which upheld the majority of Casement’s charges against the king and his brutish henchmen. In 1908 the Belgian government took over the administration of the Congo Free State, ending Leopold’s monopoly. The news would hardly have brought much comfort to the bereft and mutilated victims of his years of vile overlordship. Tellingly, it brought little satisfaction to Casement, either. In a letter to the Irish scholar and political activist Alice Stopford Green, another of his female champions, he wrote with startling and surely unintentional bathos, “The Congo will revive and flourish, the black millions again overflow the land—but who shall restore the damaged Irish tongue?”

Already Casement had accumulated as much experience, and made as significant a mark upon the world, as any man might reasonably expect to do in a lifetime, but he still had a long and varied way to go. In early 1908 he arrived in the Brazilian port of Pará, at the mouth of the Amazon, to take up the Foreign Office commission as consul, which put him in charge of another vast and largely undeveloped area of land that was bigger than Western Europe. On the same ship sailing to Brazil was Julio César Arana, a wealthy Peruvian rubber merchant and one of the numerous demons of depravity and greed with whom Casement was compelled to deal throughout his career as a diplomat and reformer.

From Brazil his correspondents began to hear repeated complaints of ill health, and it seems likely that his physical constitution had been permanently damaged by his years in the Congo. Photographs at this time show him thin to the point of emaciation, while his letters to family and friends include outbursts of rage against institutions in South America and the government in Britain that at times make him sound almost paranoid.

He had every cause to be so. He soon came to realize that Arana, owner of the Peruvian Amazon Company, was another Leopold, overseeing a huge enslaved army of workers gathering rubber in the Putumayo region, which encompassed large parts of Peru, Colombia, and Brazil. The treatment of them was a disgrace, and the cruelties inflicted on them were hideous. Since Arana’s company was registered in London and some of its workers were from Barbados, which was part of the British Empire, the government in London was able to investigate its activities. Casement was sent to the Putumayo as part of a British commission of inquiry. Soon, as Philipps relates, “the recitals of the atrocities poured out, including Indians lined up to see how many a single bullet would pass through, thrown into fires, buried alive, limbs and heads cut off.”

In the report Casement wrote, he claimed that the white settlers’ treatment of the native peoples of the Putumayo amounted to a genocide in progress. The worst of the overseers, Armando Normand, along with six others, had killed five thousand workers by “shooting, flogging, beheading, burning” in the seven years the company had been in operation. The report was received by officials in London with shock and outrage; one Foreign Office official, Philipps records, “forgot the diplomatic niceties” and declared Arana “an appalling criminal” who “ought to be hanged.”

Many attempts were made, by Arana and the Peruvian authorities, to block the report; nevertheless it was published in July 1912 by the British government’s Stationery Office, and Sir Roger Casement—he had accepted, with misgivings, a knighthood from King George V the previous year—became a household name. Less than two years later, in May 1914, Philipps has Casement in the London home of Alice Stopford Green, discussing with two other Irish republicans a plan to run guns into Ireland for use in an uprising aimed at severing Britain’s centuries-long hold upon the country.

The account of Casement’s last two years and his involvement with armed republicanism takes up more than half of Philipps’s book. This skews the story somewhat, since the humanitarian work Casement did in the Congo and the Putumayo far outweighs in importance his activities as a rebel.

Still, the narrative of his involvement in the Easter Rising in Dublin in 1916 and its aftermath is intricate and fascinating—for long stretches it reads like a novel by John Buchan—and ultimately heartbreaking. As World War I was raging, the man who for years had been an official of the British Foreign Office traveled to Germany with the aim of persuading Irish prisoners of war to form an Irish Brigade that would be sent to Ireland to join in the uprising against the British. Casement knew full well that he was committing treason and that he would probably pay for it with his life. Such treachery, no matter what the cause in which it was carried out, went against all his instincts as a gentleman and a Christian—“I hate what I am doing,” he wrote—yet his commitment to the fight for an independent Ireland never faltered.

The vicissitudes of his personal struggle further affected the precarious state of his health. In the spring of 1916 he was transported from Germany to Ireland by submarine; the journey was a nightmare:

They hit heavy seas off the Shetland Islands and Casement was horribly sick; the thought of the daily diet of tinned smoked ham and salmon, war bread and coffee, did nothing to help. He was exhausted yet unable to sleep with his mix of adrenaline and misery.

Worse than all this, however, was his fear that he would not make it to shore or would arrive too late. His plan to raise an Irish Brigade in Germany had failed, and so had his attempts to organize large shipments of German arms and ammunition for the rebels. After his capture he was portrayed by the British press as a ringleader of the Easter Rising; in fact, his mission to Ireland was aimed specifically at persuading the rebels to call off the insurrection, which he knew was doomed to failure and would lead to extensive loss of life. To the end, and despite what at times seemed his fanatical devotion to the cause of Irish freedom, his first and strongest concern was the preservation of that most fragile phenomenon, life itself.

The end was squalid, though he bore himself through it all with exemplary courage and dignity. The petty maneuvers of the forces ranged against him were despicable. On and off throughout his life he had kept a record, the infamous Black Diaries, of his homosexual encounters both at home and abroad.* When these incriminating volumes were discovered, British government agents showed them to selected journalists, with the aim of strengthening the case against the commutation of the death sentence that a London court had passed on Casement on June 29, 1916. The next day, the eve of the Battle of the Somme, it was announced that King George “had been pleased to degrade Roger David Casement from the Order of the Knights Bachelor.” A knight no longer, he went to his death on August 3 as plain Roger Casement; probably he preferred it so.

There were other acts of spite against him and those close to him. Shortly before the execution was carried out, Gertrude Bannister was dismissed from her job as a teacher at Queen Anne’s School, Caversham. She wrote to George Bernard Shaw, “When [Casement] was ‘sick and in prison’ & I dared to visit him & to go on doing it, it became too much for their respectability & they firmly removed me!”

Gertrude, and many others of his circle, remained true to him. One did not. In the summer of 1914, on a trip to New York, he had encountered “a burly, blond young man,” Eivind Adler Christensen, a Norwegian immigrant. Philipps suggests that Christensen “may have been selling his favours,” for he claimed to be “out of work, starving almost and homeless.” In fact, he had lodgings in the city, as well as a wife and a young son:

According to Christensen’s account, Casement, always generous to those in distress and presumably attracted to his importuner, asked him to call at his hotel the next morning, when he hired him as a manservant. It was the start of the most intense, fulfilling, treacherous and occasionally farcical relationship of his life.

Casement brought Christensen with him when he returned to Europe and used him on a number of occasions to liaise with officers of the British secret service in various European capitals. One of them, the immensely tall and splendidly named Mansfeldt de Cardonnel Findlay, in a secret meeting at the British legation in Christiania (Oslo), offered Christensen, according to him, £5,000—nearly £500,000 in today’s money—to get rid of his employer by “knock[ing] him on the head.” The details of Christensen’s machinations in relation to Casement are murky and hard to verify. What is certain, however, is that in the run-up to Casement’s trial, “word came from the British embassy in Washington that Adler Christensen had agreed to testify” against his benefactor and sometime lover. In a last letter to his Bannister cousins, Casement spoke of various friends and relatives and made certain last requests; Christensen’s name he did not mention.

From the condemned cell he also composed a valediction to “friends and well-wishers,” in which he wrote:

My last message to everyone is “Sursum corda” [Lift your hearts], and for the rest, my good will to those who have taken my life, equally to all those who tried to save it. All are my brothers now.

John Ellis, the executioner, paid him a final tribute, saying he was “the bravest man it ever fell to my unhappy lot to execute.” After the deed was done, Philipps writes, “Roger Casement’s body was wrapped in a shroud and buried in quicklime in the yard of Pentonville, a resting place he shared with Dr Crippen, among other murderers,” where it lay until 1965, when it was exhumed and transferred to Ireland, to coincide with the anniversary the following year of the Easter Rising.

Yet what is left? A headstone, a name, a handful of dust. Among the figures of 1916 he remains the most enigmatic, the most elusive. This may be due in part to the question of his sexuality—patriots prefer their heroes straight—and to the fact that he sought to prevent or at least postpone Our Glorious Revolution. Or perhaps it was more a matter of personality. In Casement, somehow the private man resisted assumption into public figure. If that is the case, all hail the unknown warrior.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·