Kelly is a former librarian and a long-time blogger at STACKED. She's the editor/author of (DON'T) CALL ME CRAZY: 33 VOICES START THE CONVERSATION ABOUT MENTAL HEALTH and the editor/author of HERE WE ARE: FEMINISM FOR THE REAL WORLD. Her next book, BODY TALK, will publish in Fall 2020. Follow her on Instagram @heykellyjensen.

In another blow to the First Amendment Rights of library users, the United States District Court for the Northern District of Florida ruled that the Escambia County school board did not violate student or author rights when it pulled And Tango Makes Three from school library shelves. This is the second ruling in a matter of months to put the approved content of public library and public school library materials into the hands of government officials.

It is also a ruling that contradicts one made in the U.S. Middle District Court of Florida in mid-August, where the judge found a Florida law used to remove books from public schools was “overbroad and unconstitutional.”

Peter Parnell and Justin Richardson, the creators of And Tango Makes Three, alongside an elementary school student in the district, filed the lawsuit against Escambia County school board in September 2023. It alleged that the district removed the nonfiction picture book about a pair of penguins at the Central Park Zoo who raised an egg together was removed by the board because it disagreed with their viewpoint. They argued the decision infringed on their free speech rights.

Escambia officials claimed that library collections were government speech. They could curate the collection as they wished and authors did not have a right to have their materials included.

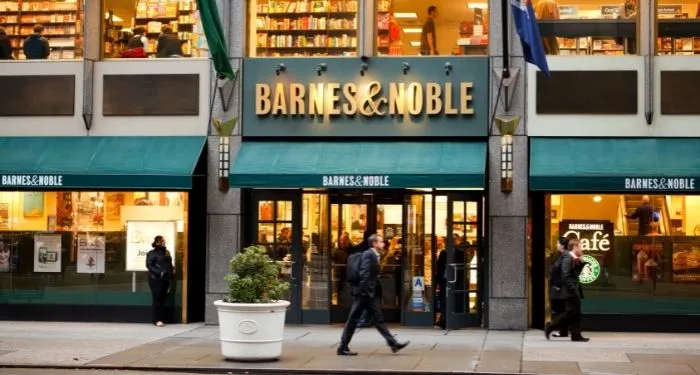

Judge Allen Winsor oversaw the case in the District Court. But rather than lean on the arguments presented by Escambia, he went with a different approach. First, Winsor argued, school libraries are not a public forum for expressing opinions. In that, the authors didn’t have the right to have their books included. Second, Winsor stated that the book being removed from the school library didn’t hinder the student plaintiff’s ability to get the book. He could “order it online, buy it at a bookstore, or borrow it from a friend.” This is a common argument made by the individuals and groups who have been pursuing book bans in public schools and libraries since the unprecedented rise in book censorship began in 2021.

Literary Activism

News you can use plus tips and tools for the fight against censorship and other bookish activism!

The New York Times’s coverage on the case points out that Winsor did not address the issue of “government speech.” Instead, Judge Winsor leaned on the First Amendment argument.

The good news is I need not decide the difficult government-speech issue to resolve the case. If book curation is government speech, the board wins on the merits because the First Amendment would not reach its speech. And even if book curation is not government speech, the board still wins on the merits: when the government decides which books to choose, it is not creating a forum for others to speak, and it is not otherwise implicating Plaintiffs’ First Amendment Rights. Either way, the First Amendment offers Plaintiffs no protection, and the board is entitled to summary judgment.

[…]

[T]here is no principled reason to distinguish book removals from decisions rejecting additions.

And Tango Makes Three was removed from Escambia Schools following a single parent complaint. After multiple review committees elected to keep the book on shelves, the parent appealed the decision to the board, who pulled it. In other words, one complaint from the community was enough to remove the book from an entire school district. Even by Escambia County’s current selection policy, removal of And Tango Makes Three–again, a work of nonfiction–would not be appropriate.

Parnell et al. vs. School Board of Escambia County is the second case this year to directly address the First Amendment rights as they relate to patron access in public libraries. The first came from the Fifth Circuit Court in late May, which argued that the First Amendment cannot be used to challenge book removals in three U.S. states. Library books are government speech and thus, not subject to the Free Speech clause–in other words, Little vs. Llano County provides fertile ground for removing materials from shelves based entirely on political motivation and sets up ample opportunity for the development of biased library collections paid for by taxpayer dollars. The ruling currently applies to Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas, but Judge Winsor pulled liberally from that case in making his decision in Parnell.

At least one of the most prolific book banners in the country, Bruce Friedman, celebrated the judge’s decision. He told Clay County, Florida, schools in a message on X that he’d be seeking to get And Tango Makes Three removed from the district soon.

This is one of two lawsuits that have been filed against Escambia County school board in relation to their mass book bannings. PEN America, Penguin Random House, and a group of authors joined with parents and students in Escambia County, Florida, to file a lawsuit against the school board in May 2023. That case is still moving through the court system.

Parnell and Richardson have filed numerous lawsuits in relation to the banning of And Tango Makes Three, which celebrated its 20th publication anniversary this year. They settled one against Florida’s Nassau County School District, wherein the board not only had to put their book and several others inappropriately removed back on school shelves, but the district also had to acknowledge their decision had no basis.

There are also a lot of unanswered questions as a result of this ruling. Where and how does this square with Judge Mendoza’s from August, wherein the law Florida instituted to remove books was deemed unconstitutional? Where and how does this decision contradict the ruling in 1982’s Island Trees vs. Pico, which held that public school libraries are places for voluntary inquiry and dissemination of information and ideas? If school and public libraries aren’t required to meet the diverse needs and interests of their communities, then what purpose do they even serve?

The future of whether or not public library materials constitute government speech remains to be seen. The plaintiffs in Parnell can appeal the decision, and the decision rendered in Little vs. Llano County from earlier this year is eligible for appeal to the Supreme Court.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·