The American Academy of Arts and Letters sits at the back of Audubon Terrace in Washington Heights, flanked by Boricua College and the Hispanic Society Library and Museum. It is one of eight Beaux Arts buildings tucked into this beautiful and disorienting pocket of Manhattan, where the names of Spanish writers, artists, and conquistadors—Cervantes, Velazquez, Columbus, Balboa—are carved into the friezes and a giant bronze sculpture of El Cid dominates the plaza. The site is a throwback to another New York, when the architecture emulated Paris and money flowed into museums instead of half-empty high-rises. Directly behind Arts and Letters is Trinity Cemetery, a nineteenth-century burial ground whose notable residents include Alexander Hamilton, John Jacob Astor, Ralph Ellison, and Ed Koch.

This Wharton-esque scene turns out to be an ideal setting for a spare, acerbic, and utterly thrilling exhibition of selected works by Christine Kozlov, the New York–born and, for a while, New York–based conceptual artist who died in 2005, at the age of sixty. Curated by Rhea Anastas and the artist Nora Schultz, the show—Kozlov’s first solo outing in the United States—is at once an appraisal of the depth and range of the New York art scene in the 1960s and 1970s and a startlingly contemporary presentation. Without leaning on a narrative of feminist recuperation or revival, Anastas and Schultz make a case for positioning Kozlov alongside her much more widely lauded male contemporaries, most notably her collaborators Mayo Thompson, of the experimental rock band Red Krayola, and Joseph Kosuth. In the show, Koslov’s work stands entirely on its own merits: equal parts playful and haunting, sometimes sinister, and always utterly serious.

Born in New York, Kozlov attended the School of Visual Arts between 1963 and 1967. It was at SVA that she met Kosuth, with whom she opened the Lannis Gallery, later known as the Museum of Normal Art. (In an essay published in 1969 Kosuth describes himself as having “founded” the space “with the aid of Christine Kozlov and a couple of others.”) The short-lived museum hosted several important shows, including an exhibition of “Non-Anthropomorphic Art” by Kozlov, Kosuth, Michael Rinaldi, and Ernest Rossi in 1967. Other collaborators included Donald Judd, Eva Hesse, Robert Smithson, Sol LeWitt, Robert Morris, and Dan Flavin; the curator and critic Lucy Lippard was named as a trustee. Kozlov was especially prolific during the 1960s and 1970s, and this is the period best represented in the exhibition. Still, you can also see a mordant collection of drawings and xeroxes from the 1990s, including newspaper images of the United States’s arsenal of B-2 Stealth Bomber jets.

In the main room sits a boxy reel-to-reel tape recorder, a snaky white cord trailing behind it toward a wall on which a text is mounted inside an aluminum frame. This is Information: No Theory (1970), and it is best described by the text that accompanies it:

- THE RECORDER IS EQUIPPED WITH A CONTINUOUS LOOP TAPE.

- FOR THE DURATION OF THE EXHIBITION THE TAPE RECORDER WILL BE SET AT RECORD. ALL THE SOUNDS AUDIBLE IN THIS ROOM DURING THAT TIME WILL BE RECORDED.

- THE NATURE OF THE LOOP TAPE NECESSITATES THAT NEW INFORMATION ERASES OLD INFORMATION. THE ‘LIFE’ OF THE INFORMATION, THAT IS, THE TIME IT TAKES FOR THE INFORMATION TO GO FROM ‘NEW’ TO ‘OLD’ IS APPROXIMATELY TWO (2) MINUTES.

- PROOF OF THE EXISTENCE OF THE INFORMATION DOES IN FACT NOT EXIST IN ACTUALITY, BUT IS BASED ON PROBABILITY.

First shown at “Conceptual Art and Conceptual Aspects,” a landmark exhibition held at the New York Cultural Center in 1970, the piece has many of the obvious markers of conceptualist practice: a preoccupation with time, duration, and the dialectic of presence and ephemerality, which is another way of saying a preoccupation with where, exactly, the work is. (The answer is, in no one place.) Information: No Theory also engages with the specter of surveillance: we are, it’s helpful to remember, only a couple of years out from Watergate and Francis Ford Coppola’s eavesdropping neo-noir The Conversation (1974). But even as Kozlov’s piece activates our paranoia—“all the sounds audible in the room will be recorded”—it also reassures us, unsettlingly, of our own inconsequence. The sounds we make will be erased, written over as so much “old information.”

Kozlov invites us to contemplate our attachment to our own ontological signature, our desire to leave some trace of ourselves in and upon the world. In a droll bit of mise-en-scène, the gallery windows on either side of her tape recorder look out on Trinity Cemetery, with its rows of gravestones and marble tombs. These shrines to personal identity are roped into a relationship with Kozlov’s piece, which promises to eliminate what the cemetery has managed to retain. The juxtaposition makes an unexpected comment on the relationship between aesthetics and social history. It suggests a palimpsest of different New Yorks not so much overwriting as ironizing one another, the world of Gilded Age luminaries jostling against that of an either overtly or implicitly anticapitalist artistic practice that strives to circumvent its own commercialization.

*

Kozlov’s intensely cerebral oeuvre also offers some sensual pleasures, thinned out but unmistakable. Kneeling down beside that recorder to catch the liquid hiss of its tape sliding around the reels, I felt like one of the patrons of the Scope, the bar with the “strictly electronic music policy” that Oedipa Maas visits in Thomas Pynchon’s 1966 novel The Crying of Lot 49. As the Scope’s bartender says, “We got a whole back room full of your audio oscillators, gunshot machines, contact mikes, everything man.” (The passage may allude to the San Francisco Tape Music Center, the experimental hub spearheaded by Ramon Sender, Morton Subotnick, and Pauline Oliveros in the early 1960s.) In Pynchon’s novel, the idea that a crowd of drunks would fall silent to listen to a “chorus of whoops and yibbles burst[ing] from a kind of juke box” is played for laughs (“That’s by Stockhausen”), but Kozlov’s show is full of these sorts of idiosyncratic opportunities, whether in the whirl of a tape recorder or in the improvisational clamor of her performances with the Art & Language collective, played here on a video monitor in black and white.

The most radical aspect of conceptualism is its ambivalence or downright disdain toward institutional capture, its desire to tweak the elementary assumption that if an artist has agreed to show her work there must be something for people to see—and, by extension, to buy. In one room of Arts and Letters, there is a framed telegram addressed to the Morsbroich Museum in Leverkusen, Germany. The museum had invited Kozlov to contribute to an exhibition, and in her telegram she offers to send “a series of cables during the exhibition [that] will supply you with information about the amount of concepts that I have rejected during that time.” “This cable,” she adds, “and the ones following will constitute the work.” On the other side of the gallery, a stack of blank paper is identified, by a sentence typed out on the top sheet, as “271 BLANK SHEETS OF PAPER CORRESPONDING TO 271 DAYS OF CONCEPTS REJECTED.” By dispersing or dislocating the object itself, Kozlov challenges not only conventional notions of the work of art as discrete, whole, autonomous, and reliant on the artist’s singular, virtuosic skills, but also the political economy of the art world, driven as it is by the will and taste of the private collector or else by major museums, whose interests tend to align with those of their corporate sponsors.

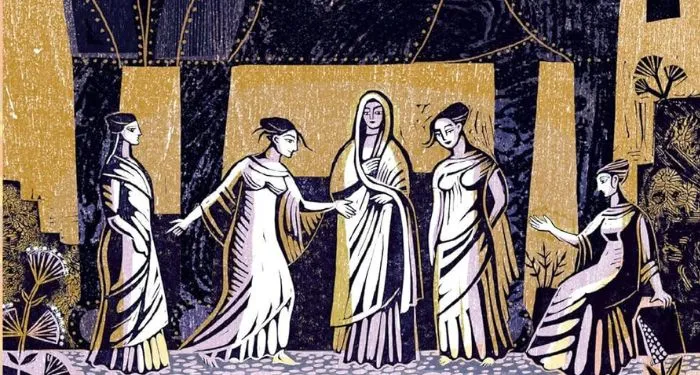

Similarly, two small, nearly square paintings from the late 1960s, A Mostly Painting (Red) and Untitled (After Goya), play with the décalage or gap between image and text as representational systems. Untitled (After Goya) refers to a pair of late eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century paintings by Goya—La maja desnuda and La maja vestida, or The Nude Maja and The Clothed Maja—depicting a fashionable lower-class woman (or maja) in states of undress and dress, respectively. In its day La Maja Desnuda was sufficiently scandalous that it was kept by its owner, the Spanish Prime Minister Manuel de Godoy, in a private room reserved for sexy paintings, along with Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus. In 1808 Godoy, his personal curator Don Francisco de Garivay, and Goya all fell afoul of the Spanish Inquisition, but Goya managed to escape prosecution when officials accepted his claim that he was following in a well-respected tradition—that is, painting naked women in the style of Titian and Velázquez, as opposed to painting naked women merely as smut.

Kozlov’s Untitled (After Goya) uses this art-historical anecdote as a launchpad for a thought problem at once philosophical and feminist. A canvas painted entirely gray except for the white block capital lettering spelling out “LAS MAJAS,” the work plays on the non-identity between what semioticians call the signifier, such as a word, and the signified, or the concept or meaning the word picks out. In this case, the phrase evokes Goya’s two paintings as a single unit without referring to them directly. Offering itself as an abstraction or, better, a radical attenuation of those lush eighteenth- and nineteenth-century canvases, Kozlov’s work prompts the viewer to think about the relation between a concept (or memory) of the paintings and the paintings themselves, and about what, if anything, of the aura of exceptionality that surrounds a great work of art may be communicated merely by its name. But there is more going on here than a coy postmodern game. Kozlov’s gray and white canvas suggests a black-and-white photograph or else newsprint, hinting at the reduction of Goya’s paintings, and perhaps figurative painting more generally, to a kind of reportage.

Given the history of La maja desnuda, Kozlov’s painting also invokes the generic status assigned to the female body in Western art—think of Godoy with all his nudes in one room. The difference between a maja clothed or naked is perhaps negligible, Kozlov implies, when even her name is unknown. At the same time, Kozlov is eager to absent herself from her own objects, in acts of self-erasure that might hint at a wish not to join the long line of infinitely iterable female bodies indexed by the words “Las Majas.” One of the vitrines at Arts and Letters includes a poignant document on which Kozlov has recorded the names of the artists represented by the Leo Castelli Gallery—two out of the thirty-three are women—and written “our ‘token’ participation reinforces + supports the gallery system which has both historically excluded and exploited us. The point is that ‘token inclusion’ of the select few undermines our potential organization in the art community.” To refuse tokenization is also to refuse interchangeability; to make oneself almost invisible is to escape being merely “one of the girls.”

*

There is, throughout this exhibition, a noticeable absence or obsolescence of the artist’s hand, in counterpoint to the idealization of the gesture that famously defined American painting during the 1950s and 1960s. While Kozlov diffuses her work across multiple sites of creation and reception, she also all but completely conceals her own tracks, using a variety of technologies to distance herself from her mark: xerox, photostat, typewriters, telegrams, and a writing instrument that might have been a DINgraph, a handheld tool that allows for an almost perfect mimicry of printed text. All this is a meaningful departure from the more traditional, not to say patrimonial, notions of attribution and credit that even many male conceptualists (Kosuth among them) had trouble relinquishing. At a moment when feminist art was beginning its association with the messy, inconvenient, grotesque, and often flagrantly erotic intrusion of the body into the proverbial white space of the gallery, Kozlov’s work tended stubbornly in the other direction. She steps backward from the social logic of personhood and the economic precepts of ownership and property to develop a practice that is material, even sensuous, without being constrained either by its own objectification or by that of the artist herself.

At the same time, an emphasis on repetition runs throughout this show, putting Kozlov in the company of other women artists and writers who, also in the 1960s and 1970s, embraced seriality as a feminist (and leftist) riposte both to the mechanized regimes of industrial production and the airless myth yoking genius to originality. In Eating Piece (2/20/69–6/12/69), Figurative Work No. 1 (1969), Kozlov writes down what she ate every day for a period of four months; Information Drift (1968) is a mounted analog tape on which news bulletins of the shootings of Andy Warhol and Robert Kennedy have been recorded, suggesting the artist at home with her radio on, maybe working, maybe doing chores, maybe doing nothing at all.

Like Bernadette Mayer’s Memory, a collection of journal entries and photographs made every day during the month of July 1971, or her Midwinter Day, a long poem written over the course of twenty-four hours, these pieces are immersed in the ordinary not as an alternative to the more public reality of the newsreel, or the grand narrative of the artist isolated from the quotidian, but as the material condition of aesthetic and intellectual life. They take hold of dailiness, subjecting its traces to philosophical scrutiny and singling out art as precisely that form of human labor that toggles philosophy and existence. Their theme is the moral weight of that proposition.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·