All we know of Saint Hilda of Whitby, the founding abbess of one of the most important monasteries of Anglo-Saxon England, comes from some nine paragraphs in Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, completed around 731 CE. We know that she was born in 614 to Hereric and Breguswith, and that she had an older sister, Hereswith, whose son became king of the East Angles. We know that Hereric, a prince of the royal family of Deira, was poisoned while in exile when Hilda was an infant; that Breguswith raised her and Hereswith in the court of Hereric’s uncle, King Edwin; and that at the age of thirteen Hilda was baptized into the Roman Catholic faith by Bishop Paulinus at York.

Bede divides Hilda’s life in half, devoting just a few words to her first thirty-three years, spent “living most nobly in the secular habit,” and far more to the remaining thirty-three, lived “still more nobly,” devoted to God “in the monastic life.” Sometime around that transition, he writes, Hilda intended to travel to Gaul from the East Angles, but she was persuaded to stay in Britain by Bishop Aidan and, in 657, founded a monastery at Streanaeshalch (later renamed Whitby), at the mouth of the River Esk.

Bishops and kings apparently held Hilda in high regard for her faith and “innate wisdom.” We know that the Northumbrian Church convened a synod at her monastery in 664 to debate the significant issue of whether to follow Roman or Celtic traditions regarding Easter. (The ruling was in favor of Rome, a decision that shaped the practice of Catholicism in England ever after.) Bede includes specific mention of Hilda in describing the parties’ differing opinions (she was for the Celts). Finally, we know that on November 17, 680, at the age of sixty-six, Hilda “joyfully saw death come, or, in the words of our Lord, passed from death unto life.” So profound was her passing, Bede tells us, that two nuns in different monasteries had visions of her soul ascending to heaven.

Bede’s English history covers a period of nearly eight hundred years, yet it mentions only about forty women, mostly in passing. Hilda is one of just three abbesses whose lives it details. As Mary Wellesley has pointed out in these pages,

In each of these accounts he probably used sources that originated in these abbesses’ own institutions and that were either female-authored or based on female testimony. But this source material is never cited, probably because he felt it lacked authority.

Instead Bede “filleted out what he needed,” gliding over significant parts of his female subjects’ lives and shaping their stories “into a form that suited his aims,” in part to present them as models of chastity.1 Still, were it not for his inclusion of Hilda, we might have no record of her at all.

For the British American writer Nicola Griffith, “all we know” is sufficiently tantalizing. “We have no idea what she looked like, what she was good at, whether she married or had children,” she writes.

But clearly she was extraordinary. In a time of warlords and kings, when might was right, she began as the second daughter of a homeless widow, probably without much in the way of material resources and certainly in an illiterate culture, and ended up a powerful adviser to statesmen-kings and teacher of five bishops. Today she is revered as Saint Hilda.

Hild (2013), the first in Griffith’s projected four-volume series of epic historical novels, envisions the life of Hilda—or Hild, as Griffith renders it—from ages three to eighteen in nearly 550 pages. The second book, Menewood (2023), picks up where Hild leaves off and is more than a hundred pages longer, though it spans only three years. What Griffith seeks to explore is how a woman of modest means became one of the most influential people in the violent, patriarchal society of seventh-century Britain. That requires not just good storytelling and prose, though the novels have those, but a critical analysis of the historical record, the political power available to women, and how people, then and now, discover their sense of self, as well as an imagination robust enough to enrobe in flesh a skeleton of cold facts.

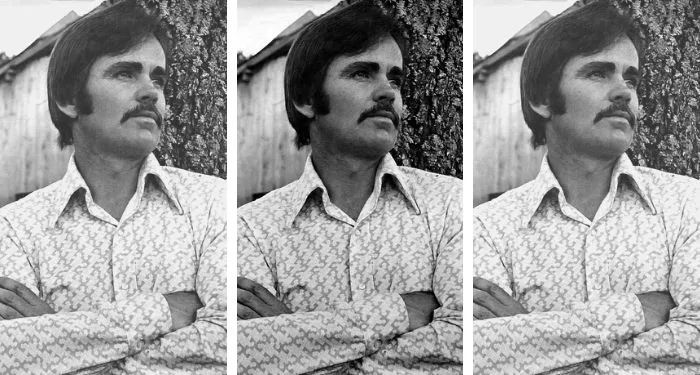

Griffith was born in the northern English city of Leeds in 1960. At the age of fifteen she got her first paid job, working on the excavation of a Roman villa near Helmsley, in North Yorkshire. She briefly studied science at university before dropping out and fronting an all-girl band called Janes Plane; she also studied martial arts and worked as a self-defense teacher. She attended her first Clarion Writers Workshop in Michigan in 1988 and moved to the United States the next year.

Griffith began her writing career with science fiction. Her first novel, Ammonite (1992), imagines the planet Jeep, on which only women can survive a mysterious virus. Marghe, an anthropologist from Earth hired by an authoritarian conglomerate called Company, ventures among the planet’s tribes to test a vaccine and learn the secrets of their ability to reproduce without men. The book is an amalgam of Joanna Russ’s and Suzy McKee Charnas’s radical feminism and Ursula K. Le Guin’s anthropological interests. Griffith has since written Slow River (1995), another science fiction novel; a crime trilogy about a female ex-cop named Aud Torvingen2; a multimedia memoir; So Lucky (2018), a noirish novel about chronic illness and disability (Griffith was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1993); and Spear (2022), a queer retelling of the Arthurian legend of Percival, or Peretur, with a disguised young woman in the role of hero.

In tackling Hild’s story, Griffith found that the extrapolative techniques of science fiction were, as she told The Paris Review Daily, her “meat and drink—take three facts and build a world from it.” But the Hild novels aren’t science fiction or fantasy. Into each novel Griffith poured roughly a decade of research—about subjects as varied and wide-ranging as martial iconography, herbal medicine, Anglo-Saxon attitudes toward slavery, the production of parchment and ink—to create a historically accurate environment for her heroine. When asked how she navigated the question of when to write speculatively about Hild’s place in historical events and when not to, she explained: “For me, the rule was very simple—if it could have happened, it was fair game. If it was actually written down, I was not going to contravene it.”

Bede’s Hilda, though, wasn’t entirely ordinary. He writes that when she was an infant, her mother had a vision of a precious necklace that “seemed to shine forth with such a blaze of light that it filled all Britain with the glory of its brilliance.” Griffith builds her character’s trajectory around this dream of Hild as “the light of the world,” prophesied to guide the paths of kings.

In her novels, as in Bede’s account, Hild and Hereswith are the children of an exiled, murdered prince. Griffith elaborates, creating for the sisters a situation of uncertainty and threat—without the protection of a king, they are essentially alone in the world. To safeguard her daughters, the cunning Breguswith arranges for Hereswith to make a politically advantageous marriage and encourages belief in Hild’s supernatural abilities by spreading the story of her vision and by teaching Hild to observe and analyze everything that goes on around her. King Edwin, intrigued by Hild’s rumored precognition, takes her on as his seer when she is seven. She dispenses advice in the form of visions or prophecies, and at nine she begins traveling on the war trail with his army and on equally perilous diplomatic missions with a smaller band of warriors known as gesiths.

Two centuries after the end of Roman rule in Britain, it is now a period of Anglo-Saxon expansion; incursions by Picts, Scots, Welsh, and Irish; and efforts to convert the population to Christianity. To rule during this era is to knit together areas of disparate peoples, maintain a complex trade network, and fend off challenges for the throne. Power mixes easily with paranoia, and Edwin, who desires to “build a kingdom to last longer than song itself,” is eager for every advantage available to him—church and seer, might and subtlety. Hild must navigate Edwin’s moods and the growing influence of his bishop, Paulinus, an ambitious and formidable man who seeks to Christianize the whole of Northumbria.

Hild is unusually tall—not long after puberty, she towers over most men. Strong and agile, she doesn’t feel the extremes of cold weather. She learns to battle with a staff (swords are “man magic”) and understands the powerful symbolism of dress in political situations: “Blue-green veil band embroidered with gold-and-silver thread, sewn with lapis and agate and beryl…. No one would be fool enough to get in the way of this woman.” She can choke a man to death with her staff, and she knows the best earrings to bring out the color of her eyes.

It’s easy to forget that for most of the novel Hild is a child—what ten-year-old wears a slaughter seax on her belt? Her developing sense of self guides the reader through the dense plot. At the beginning of Hild, she plays in a hazel coppice with her friend Cian. Alone together, Cian mimes the swordplay of great battles past while Hild absorbs the sights and sounds around her. “She liked time at the edges of things,” Griffith writes. “The edge of the crowd, the edge of the pool, the edge of the wood—where all must pass but none quite belonged.”

The court travels with Edwin’s annual tour of the regions of his kingdom, during which Hild witnesses the economics of quotidian life. A piece of cheese is “a product of a well-run world in the palm of her hand”: it represents a yearslong process of sheep husbandry, a proper milking schedule, fermentation, cooking, storage, and aging. With each passing year and each trip round the kingdom, Hild’s understanding deepens. “Dogs own space and cats own time,” she tells the queen, Æthelburh. “Kings travel from place to place like a cat but want to own those places like a dog. It’s why there are wars.” Out in the woods or within the royal estate, she sees “an endless song of life around her, eating, crying, dying, breathing, breeding,” yet also begins “to feel her own rhythm.”

In Griffith’s hands, a conversation between Hild and Æthelburh as they sit on a riverbank is as thrilling as a spear thrust through a man’s cheek. The language is rich and abundant with details of the environment’s flora and fauna, almost Edenic in its plenitude; each page beats with life. Hild finds a texture, an extra dimension everywhere: rain sounds “personal, private”; the air smells “secret and satisfied”; a man speaks passionately, “spattering words about him like molten glass.” While drawing a map of the British isle in the dirt for Edwin’s children, Hild names the land’s many rivers—“The great Treonte, which flowed up through Lindsey, north and east into the Humbre. The Daun into the Treonte. Her own Yr, which moved south and east to join the great Use, which, in its turn, joined the Humbre”—in a litany that recalls the cumulative magic of John Ashbery’s poem “Into the Dusk-Charged Air,” a long catalog of rivers from around the world.

When Hild is a teenager, her feelings of erotic pleasure sometimes color the natural world until it’s impossible to separate the two:

Midsummer in Caer Loid…where the skeps would be humming, the plum trees beginning to show dabs of colour as the fruit warmed in the sun, and the fish in the beck packed close enough for children to walk across on their backs. The vill would be waiting, sleek and heavy-lidded—

It’s tempting to characterize Hild as a bildungsroman. Hild certainly develops morally and psychologically over the course of the novel, growing into an astute and wily participant in the political world of the court. But her mother has encouraged her potentiality as a seer from an early age, advising her repeatedly, “Quiet mouth, bright mind.” She seems born into the uncanny, venerated and feared for her special abilities rather like Alia in Frank Herbert’s Dune, accruing epithets and identities like beads on a necklace:

She was an ælf, a freemartin, a hægtes. She was an angel, a maid, a butcher-bird. She was rich, she was subtle, she could break your mind and read your heart. She had the ear of the king. The mouth of the gods.

A list of characters doesn’t appear until Menewood (good luck keeping track of Osric, Oswald, Oswiu, Oswine, Osfrith, and Osthryth without it), but both novels contain maps, family trees, and glossaries, from which we learn that a “freemartin” is a “female calf masculinised in womb by male twin” and a “hægtes” is a “formidable woman, user of uncanny power.” Griffith provides assistance with pronunciation, too, as seventh-century Britain swirled with Old Irish, Brittonic, Latin, and Old English—hence names like Gwladus (OO-la-doose) and Eanflæd (AY-on-vlad) and words such as “gemæcce” (yeh-MATCH-eh), a formal female friendship or “heart friend.”

When Hild is eleven, she advises Edwin to take the town of Lindsey, using a dream and a prophecy to persuade him. He brings her to the battle, partly as a threat in the event she is wrong. During an ambush, “shrieking like a gutted horse,” she half falls, half leaps from the tree where she has been hiding, knife drawn. When Hild comes to, she “wiped the blood off her face with a wet dock leaf and nodded. It wasn’t her blood. It was the blood of those who had fought over her like mad beasts while she lay stunned.”

In Edwin’s tent after the skirmish is won, she recognizes a Welsh enemy captive and speaks to him in British, a language that she knows Edwin’s chief gesith—an Anglisc speaker—can’t quite understand, in order to get valuable information for later use. Gossip among the gesiths transmutes these events into an otherworldly affair: she had foreseen the identity of the captive and “witched” him, and instead of tumbling out of the tree, she “fell from the sky like an eagle.” A group of gesiths begins to follow her out of fear and awe; to others, she is “not human, more like a wall, a tide, the waxing of the moon. A force of nature. Implacable, untouchable.”

Menewood bears the fruit of this reputation-building. The novel is bookended by two battles: one at Hæðfeld, where Edwin is killed (no spoilers there—it’s historical fact), and another near Heavenfield, where Oswald of Bernicia defeats Edwin’s killer, the barbarous Cadwallon of Gwynedd, and becomes the Northumbrian overking. At least a third of the novel is cradled in a profound grief (here, I won’t spoil), and that anguish reaches far into the rest of the book, even as Hild begins the daunting task of rebuilding Northumbria’s ruined infrastructure and alliances and mounting an offensive against Cadwallon: the towns are ransacked and burned, the population is either murdered or starving, and the ruling family is either dispersed or dead. Griffith has so thoroughly realized her characters that certain deaths catch the reader like a knife in the ribs. (This reader cried several times.)

After the death of Edwin and his sons, Hild is among the last living members of the family dynasty and in a prime position to claim the throne. But she doesn’t want it. The fate of all kings, she thinks, is to end “bleeding into the mud of the battlefield, whimpering in fear and pain.” All Hild wants is a land of her own, where she can be at peace and relatively independent. That land is “a valley with bog and beck and bramble” hidden in the woods of Elmet (now West Yorkshire), which she discovers in the first novel. Before his death, Edwin gives her this “mene,” and by the opening of the second novel, she has begun building it into a small, secret community where she and others take refuge as Cadwallon sweeps across the kingdom.

Hild’s ability to ramble among languages serves her well in slyly sussing out allegiances and gathering information. Languages have distinct qualities, which Hild thinks of in tactile, often geographical terms. Frankish is “a strange, Latin-stained tongue,” and Irish has a “dark liquid gleam.” Anglisc is “the up-and-down of the Welsh hills, with a skirl of wind and a hint of brook.” British is “the language of the high places, of wild and wary and watchful things. A language of resistance and elliptical thoughts”; it is also “the language of kin-killing and clan feud.” The land itself is also a source of intelligence, even in postwar disarray. In need of a way to feed her growing community, Hild hears what sounds like a shepherd’s whistle and, realizing that it is the mimicking call of starlings flying south, gleans that there are still places north where shepherds are tending flocks.

Everything—in nature, society, and religion, as well as her wyrd, or fate—is part of a pattern, “the living weave of weather, of wave and wood, of wishes and wyrd, hope and happiness. It’s the breath of the world…. We all hear it, we feel it, we breathe it. It sings in us.” She takes comfort in the idea that “it wastes nothing, the pattern”—that each event in one’s life is woven into a greater picture and that even tragedies and disasters have a purpose. This sensibility echoes her drive for fellowship and common cause and informs her “true sight,” which involves “letting the thoughts come, letting the things she already knew arrange themselves in a pattern, a story that others might call a prophecy.”

Though a deeply pleasurable novel, Menewood doesn’t always have the quick pulse of Hild. The tantalizing arc of Hild’s ascent in Edwin’s court can’t be replicated in a sequel, and though Menewood contains many fine moments—including scenes involving Hild’s female lovers and friends; the slaughter at Hæðfeld, which evoked for me Bruegel’s painting The Triumph of Death (1562–1563); and Hild’s darkly victorious ride against Cadwallon—its long middle section in Menewood sags. The novel is so much about safety—the catastrophic loss of it and Hild’s single-minded desire to regain it—that the word appears in some form every few pages, a nagging refrain.

Menewood is a frictionless hideaway where problems are efficiently solved and all inhabitants play a part in the hive of industry, each according to their ability. In this sense it is rather like the world of Lauren Groff’s Matrix (2021), a novel about the late-twelfth-century poet Marie de France that is set almost exclusively within the walls of an English abbey, where work promises reward and protection is the watchword.3 Like Griffith’s Hild, Groff’s Marie is unusually tall, and Matrix invokes some of the same details—cold pottage, chaffinches, and colewort—that appear in Griffith’s books. But while both writers seek to elucidate the place of women in the historical register, Groff’s portrait of Marie reads as hagiography, and the community Marie leads is not, as she observes, “a tapestry of individual threads but a solid sheet like pounded gold.” In contrast, Griffith’s Menewood, like the larger world of Northumbria, is very much about the various threads.

And yet at times it can seem as though Griffith has pursued her subject too far into the realm of wishfulness. In Menewood, she has created a community that is egalitarian and inclusive, regardless of religious belief, physical ability, or sexual preference—a utopia in a still largely pagan, pre-Christian Britain. It’s a wonderful notion, but it has the glimmer of a dream rather than the shape of truth, even if early Christianity may have introduced a preoccupation with people’s sex lives where there had not been one; even if ancient Britain did include a diverse population; and even if, as Griffith writes, the historical Hilda’s later community at Whitby similarly “held all possessions in common and all members were treated equally.”

Griffith need not have created an idealized society in order to provide evidence of Hild’s humanity or to make notable her efforts to define her own path. In Hild and elsewhere in Menewood she is fascinating because her story, even extrapolated through fiction, contradicts what we think we know. In trying to understand the concept of sin, Hild asks her sometime confidant, James the Deacon, what counts as a lie. Amused, he responds:

“‘What counts as a lie?’ You’re as slippery as a bishop. If only women could take the vow!”

Hild said solemnly, “What, exactly, counts as a woman?”

Eventually Hild emerges from the cocoon of Elmet a changed person—the driving force of Northumbria’s future and all the more interesting for it. She sheds the mantle of hægtes and becomes flesh and blood. If men once followed her because she appeared otherworldly, now they follow her, as her adviser Gwladus tells her, “because you are exactly what you seem: a woman who wins.”

While researching Menewood, Griffith was dissatisfied by historical accounts of the Battle of Heavenfield, including Bede’s. The claim that the exiled prince Oswald’s small, underequipped band defeated Cadwallon’s overwhelming army of well-supplied fighters thanks in part to divine intervention didn’t add up. She found a more credible explanation in the possible existence of a “knowledgeable, observant, persuasive, and charismatic noble whose counsel on the dynamics of power…was sought by kings.” In her fictional telling, that noble is a woman.

And why not? How many have been left out of history’s songs or reduced to supporting players, if even that? In the 1880s archaeologists discovered the remains of a Viking buried with the accoutrements of a warrior; in 2017 the remains were found to be female, and debate ensued about whether to reinterpret the relationship between the woman and the weapons (they’re only symbolic, some argued; she wasn’t actually a warrior) and whether she and possibly other female warriors were exceptions to the patriarchal norm.

Fiction is an ideal form for illuminating the unknown aspects of historical lives. Without Hilary Mantel’s inventiveness in her Wolf Hall trilogy, for example, we would have little insight into Thomas Cromwell’s motivations and feelings. She told The Paris Review about a documented episode, shortly after Cardinal Wolsey fell from power, when Cromwell was seen crying while standing at a window holding a prayer book. Generations of historians had reported it, usually referring to it as a cynical and performative display, without ever noticing the significance of the day on which it occurred—the day of the dead. “This is a man who, in the last three years, has lost his wife and two daughters,” Mantel said.

He’s now lost his patron and his career is about to be destroyed. Once you realize what day it is, everything changes…. That strikes me as a really powerful example of how evidence is lying all around us and we just don’t see it.

Griffith’s Hild novels are written in that spirit, and in the spirit of our contemporary rediscoveries of women whose accomplishments were excised from history and from memory. “What we read as a history of our nation is a history of men, as viewed by men, as recorded by men,” writes Philippa Gregory in her recent history of England, Normal Women: 900 Years of Making History (2023). “The only women of interest to the male record keepers were mothers, queens, taxpayers and criminals.” Hilda of Whitby was none of these.

Early in Menewood, Hild envisions a form of oral history transmitted matrilineally. It reads as an antidote of sorts to the impersonal, partial histories that minimized or erased Hilda of Whitby and so many others. “I see it,” she tells Cian:

“foremothers and mothers and daughters and their daughters through the ages, standing in a line that reaches the horizon. All the same blood: Here the same eyes or catch in the laugh, there a familiar tilt of the head or snag of dogtooth against the tongue, like an echo. Or like opening a peapod, and inside finding another peapod, and inside that another.” On and on, unbroken.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·