The New Zealand novelist Janet Frame had a rather startling story to tell about the relationship between her work as a writer and her existence as a human being. Writing saved her life, she explained, and she meant it literally. In December 1952, at the age of twenty-eight, after spending more than seven years in and out of various psychiatric institutions—following a suicide attempt in 1945 and a hurried diagnosis of schizophrenia—she was institutionalized again and scheduled for a leukotomy, or prefrontal lobotomy. Her mother had signed the consent form. In anguish and fear Frame was counting down the days till the surgery when her short story collection The Lagoon won what was then New Zealand’s most prestigious literary award, the Hubert Church Memorial Prize.

I repeat that my writing saved me. I had seen in the ward office the list of those “down for a leucotomy,” with my name on the list, and other names being crossed off as the operation was performed. My “turn” must have been very close when one evening the superintendent of the hospital, Dr Blake Palmer, made an unusual visit to the ward. He spoke to me—to the amazement of everyone.

As it was my first chance to discuss with anyone, apart from those who had persuaded me, the prospect of my operation, I said urgently, “Dr Blake Palmer, what do you think?”

He pointed to the newspaper in his hand.

“About the prize?”

I was bewildered. What prize? “No,” I said, “about the leucotomy.”

He looked stern, “I’ve decided that you should stay as you are. I don’t want you changed.”

This last-minute reprieve was the beginning of a slow return to life outside institutions (although Frame would later voluntarily spend two long spells in the Maudsley Hospital in London, where she was told that she did not suffer—and never had—from schizophrenia). She went on to publish eleven novels and numerous short stories, to travel (she lived in Ibiza and England and spent long periods of time in the United States), and to win many more prizes and awards. Eleanor Catton’s assessment of Frame as “the greatest New Zealand writer…utterly herself” is now regularly printed on the covers of her novels. But it is her three-volume autobiography, An Angel at My Table (1982–1985), that readers tend to know, and more familiar still is the 1990 film adaptation, directed by Jane Campion, with an astonishing performance by Kerry Fox as the pathologically shy and fragile grown-up Frame.

Writing was Frame’s guardian angel and savior, Campion’s film says, as it plots the close relationship between her personal losses (a twin lost in utero, two sisters drowned due to the same undiagnosed heart conditions, a brother disabled by epilepsy, and the catastrophe of hospitalization) and her ability to transform these experiences into art. Writing kept her alive. But the link between her life and her writing also became a burden, as she increasingly felt trapped by biographical readings of her fiction that located her “genius” in her “madness.” As though to throw readers off the scent, she filled her novels with alter egos, substitute personas, pseudonyms, naming games, and decoys. In 1958 Frame changed her own surname to Clutha, after a river on New Zealand’s South Island. It was less dramatic than the arrival of Dr. Palmer into the back ward of the asylum brandishing a newspaper, but it was another example of how to survive in language.

Frame’s insistence on the gap between her fiction and her autobiography was not unreasonable, but it was complicated by the novels’ persistent yoking of madness with imaginative insight, their repeated assertion that reality was not to be found in the external world of action and other people but only, as she put it in a 1970 interview, in the withdrawn world of “life within.” Her first slippage beyond what she termed the “normal” had occurred in the final year of her degree in teaching, when faced with a school inspector sitting in her class: she found herself mute and eventually walked out of the school, never to return. John Money, a young psychology lecturer at the University of Otago (renamed John Forrest in her autobiography), took an interest in her and recommended a rest cure at Dunedin Hospital, in a ward that, “I was soon shocked to find, was a psychiatric ward.” This marked the beginning of a period of eight years spent moving in and out of closed psychiatric institutions.

From Dunedin she was taken to Seacliff in Oamaru (“where the loonies went”), with later admissions to Sunnyside in Christchurch and to Avondale in Auckland. She received over two hundred electric shock treatments (without muscle relaxant or anesthesia, “each the equivalent, in degree of fear, to an execution”) and was put in insulin comas, locked in back wards, and—in the end—scheduled for brain surgery.

The stories that won her the Hubert Church Memorial Prize were written in spells outside the hospital. Soon after her first in-patient stay at Seacliff she had looked up schizophrenia in a psychology textbook and found it described as “a gradual deterioration of the mind, with no cure.” She applied for a job as a maid in a boardinghouse for the elderly in Dunedin and, as she later described it in An Angel at My Table, tried to come to terms with her new reality:

My life away from the boardinghouse consisted of evening lectures on logic and ethics, and weekly “talks” with John Forrest in a small room on the top storey of the University building known as the Professors’ House. I also spent time in the Dunedin Public Library, where I read case histories of patients suffering from schizophrenia, with my alarm and sense of doom increasing as I tried to imagine what would happen to me. That the idea of my suffering from schizophrenia seemed to me so unreal, only increased my confusion when I learned that one of the symptoms was “things seeming unreal.” There was no escape.

My consolation was my “talks” with John Forrest, as he was my link with the world I had known, and because I wanted these “talks” to continue I built up a formidable schizophrenic repertoire: I’d lie on the couch, while the young handsome John Forrest, glistening with newly applied Freud, took note of what I said and did, and suddenly I’d put a glazed look in my eye, as if I were in a dream, and begin to relate a fantasy as if I experienced it as a reality. I’d describe it in detail while John Forrest listened, impressed, serious. Usually I incorporated in the fantasy details of my reading on schizophrenia.

John Money mostly gets a pass in accounts of this period in Frame’s life—he collected the stories she gave to him and arranged for them to be published by Caxton Press. To that extent he was on the side of the angels. But he was a man with seemingly limitless confidence in his own abilities. He was a twenty-four-year-old junior lecturer with a master’s degree in psychology when the twenty-year-old Frame took his class at the University of Otago. He seems to have had no compunction about attempting to analyze Frame, though the task went way beyond his pay grade. He later earned a Ph.D. at Harvard, where where his studies focused on “hermaphrodism,” and was the psychologist in a notorious gender reassignment case in the 1960s. After a botched circumcision when David Reimer was eight months old, Money persuaded the baby’s parents to allow gender reassignment surgery and bring their son up as a girl, with disastrous results. Unlike Dr. Palmer, he was, in effect, declaring, “I do want you changed.” It is frightening to contemplate the sheer power these medical experts wielded over their isolated and vulnerable patients.

Frame continued to lean on a series of male authorities over the years after her release from hospital, often at great cost, but it is not clear where else she could have turned if she was to fulfill her ambition, or rather her need, to write. Her first novel, Owls Do Cry, was written in the eighteen months after she was declared sane and while she was living in a hut in the garden of the novelist Frank Sargeson in Takapuna, a suburb of Auckland. It is set in the fictional town of Waimaru (based on her childhood home in Oamaru) and recounts the fortunes of the Withers family, “using people known to me as a base for the main characters.”

Daily life for Bob and Amy Withers in their isolated home is rackety and underfinanced; the children (Francie, Toby, Daphne, and Chicks) cling to their world of imaginative play, hunting for “treasure” at the town dump and retreating from the realm of school, and later work in the local mill. One sibling, Daphne, appears to dream much of the novel from inside the ward of a psychiatric hospital where she is kept in “the dead room”:

And Daphne lived there alone for many years, amid the assault and insinuation of sound in days unshining and nights without darkness…. And the struggle to take hold of time between the slat-shadows of an unreal sun, for there the day is day but never.

But Daphne herself is not a writer—her way out of the hospital involves undergoing rather than escaping the leukotomy; the surgery “changes” her sufficiently so that she can settle into a job at the mill. It “normalizes” her. This is not the novel’s only departure from Frame family history. Daphne’s older sister, Francie, dies not by drowning in the town pool but by falling into a bonfire in front of her horrified siblings; no one goes to a university where they read Freud, T.S. Eliot, James Frazer, Jung, Dylan Thomas, and George Barker, or obsess over Coleridge’s theory of the primary and secondary imaginations, as Frame did.

Instead the novel generates the aura of imaginative creativity through the siblings’ responses to the natural world, their games, and their language. Daphne’s inner life is her only life, and the same is true for her epileptic brother, Toby, shunned by most people in town. The plot depends on a rather stark distinction between middle-class conformism (typified by the youngest sister, Chicks, an updated Rosamond Vincy, whose ambitions—which we get in the first person through extracts from her diary—are those of a stereotypical 1950s housewife) and the creative souls of the sick and the outcast.

When the book was published in 1957 it caused a sensation in New Zealand; as Jane Campion recalled, “It was hailed as the country’s long-awaited first great novel.” Campion encountered the book at the age of fourteen, “when my life felt like torture”:

It was this inner world of gorgeously imagined riches that Janet affirmed in Daphne, but also in me, and quite probably in all sensitive teenage girls. We had been given a voice, poetic, powerful and fated—a beautiful, mysterious song of the soul.

What Campion read as the cry of misunderstood girlhood was upheld by the New Zealand cultural nationalists of the 1950s, impatient with a white settler colonial mindset obsessively turned toward Europe, as the voice of an untamed nation. The writers associated with Caxton Press championed “Speaking for Ourselves,” as the title of Frank Sargeson’s 1945 anthology of short stories put it, rather than aping the literary and artistic culture of London and Paris.

The poet Allen Curnow argued that New Zealand “remains to be created—should I say invented,” and advocated local settings and an appreciation of the physical landscape, its dialect, and its history. From today’s perspective the movement’s lack of any real engagement with Maori culture is glaring. It suggests that the driving force behind it was a form of romantic mythmaking rather than a political commitment to the realities of New Zealand’s varied histories and languages. But Frame’s elevation of local “treasure” over philistine suburban domestic conformism fit right in.

Sargeson really was an enabling spirit. He encouraged Frame to develop a writing routine; he fed her three square meals a day, provided a social life when she needed it, and advocated for funding that would allow her to travel to Europe. She left New Zealand in late 1956 and spent much of the next seven years in London, living in lodgings in Clapham Common, Kentish Town, and Camberwell; encountering amorous West Indian immigrants and a bossy, puritanical Irish fellow lodger; working for a short spell as an “usherette” at a cinema in Streatham; and admitting herself to the Maudsley when she fell into depression.

There she found another supportive figure in the psychiatrist Robert Cawley, whom she first met while an in-patient in 1957 and whom she saw twice a week for three years from 1959 to 1961. (She described him as a combined “friend-priest-husband-father,” “with the manners of an angel,” and went on to dedicate seven books to him.) Believing that Frame was not schizophrenic but suffering the effects of her violent incarcerations, Cawley encouraged her to write about her experience of hospitalization. The result was a second semiautobiographical novel, Faces in the Water, published in 1961—the same year as Michel Foucault’s Folie et déraison (later translated as Madness and Civilization) and Erving Goffman’s Asylums, and two years after R.D. Laing’s The Divided Self.

The narrator of Faces in the Water is Istina Mavet (the name joins the Serbo-Croatian for “truth” with the Hebrew for “death”), a woman who cycles through the brutal asylum system over a number of years, is shocked, drugged, punished with solitary confinement, and eventually released. When I first read the novel I assumed that Frame must have been familiar with Goffman’s essays on “total institutions,” based on his research in St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C., which he published in the late 1950s and which were later combined in the 1961 book. There were too many echoes to be coincidental. The account of the punishments and rewards of the system, the public-facing wards masking the violence and horror of the back wards, the inmates who must learn to perform their consent to the codes and language of illness and recovery in order to survive, the patients who are stuck in the hospital because no one else will have them, the apathy of those who have given up: the two books dovetail to an extraordinary degree, Goffman’s an analytical account and Frame’s a story told from the inside.

I now think I was wrong: what the shared language reveals is the awful similarity in psychiatric care across the Western world before the combined effects of more humane attitudes toward those suffering from mental illness and the release from institutionalization offered by psychotropic drugs. Indeed, Michael King’s biography of Frame, Wrestling with the Angel (2000), quotes a number of letters she wrote during her incarcerations that use the same formulations about back wards and regimes of punishment and that were written long before Goffman’s essays.

But Robert Cawley would have known Goffman’s work—the publication of his research had an almost immediate effect on the drive toward the deinstitutionalization of British psychiatric hospitals. And it may well have lain behind Cawley’s conviction that Frame’s problem was not mental illness but the baleful effects of institutionalization itself.

Paradoxically for a book that is set almost entirely inside a series of closed wards, Faces in the Water is Frame’s most social novel. The characters, including the nurses and doctors, are mentally isolated but forced to relate to one another throughout the years spent living together in confinement. Frame has enormous empathy for her fellow asylum inmates (and perhaps survivor’s guilt), and she characterizes their struggles against cold, hunger, and abandonment with tenderness and care: the “feverish stowing of sandwiches into pockets” on organized “occasions”; the hierarchy of cakes—hollow and currantless for the lost causes, fancy cream for those with a bit more status in the hierarchy. She is acerbic in her judgment of the nurses in charge (“‘For your own good’ is a persuasive argument that will eventually make man agree to his own destruction”) and scathing about the shortcomings of what was called “the ‘new’ attitude” to psychiatric care (“Mental patients are people like you and me”).

The wards are understaffed, and a conversation with a doctor is an impossibility. The long-term patients cling to their few possessions and use tricks of docility and politeness to try to get the reward of a chocolate or a place by the fire. That there are any instances of kindness seems extraordinary, since everyone necessarily has to look out for themselves. But they also have to live with one another. There are moving portraits of her fellow sufferers: Alice, who worked as the ward maid,

seemed daily to grow thinner, and such was her serious, dedicated air as she worked that one could not believe her thinness to be the result of physical exertion but a spiritual consuming of herself. Her true place was aboard the Mayflower or in a Quaker Meeting House; or so one would have thought, until one saw her at night, in bed, combing her waist-long white hair, and by some magic process, as she shook her hair freely about her, unloosening her tight lips and talking, talking of the many times in her life when she had been kidnapped in broad daylight and smuggled aboard ships to the Spanish Main and borne away by wild men at dead of night to caves in the Himalayas. Held for ransom. Tortured. Threatened. And she spoke the truth. As she spoke, what the advertisers might call a “secret ingredient” passed her lips inside the words, and forced us to believe her stories.

Or Carol, an abandoned child with dwarfism, incarcerated since the age of twelve, who rationalizes her situation by explaining that since she was born “jitimate” her mother didn’t want her to grow. It’s a generous, compassionate novel that betrays a real nostalgia for the community of lost souls kept out of sight in the asylums.

Faces in the Water was written while Frame was living in a lodging house in Camberwell, supported by National Assistance—a weekly social security payment. Her third novel, The Edge of the Alphabet, first published in 1963 and recently reissued, is loosely based on her experiences of living in London at that time and reprises some of the family characters from Owls Do Cry. At the beginning of the novel Bob Withers (his wife, Amy, now dead) is seeing his son, Toby, off on the ship to England and worrying about whether he will be safe given his epilepsy. (Frame’s brother, Geordie, did follow his sister to England for a spell in 1957.) On board ship Toby encounters Pat, an Irish bus driver, bossy, puritanical (and racist), who was based on an immigrant from Mayo with whom Frame lodged for a while early in her London stay, and a young woman named Zoe, isolated, shy, a failed teacher who will later work as an usherette in a cinema in Streatham.

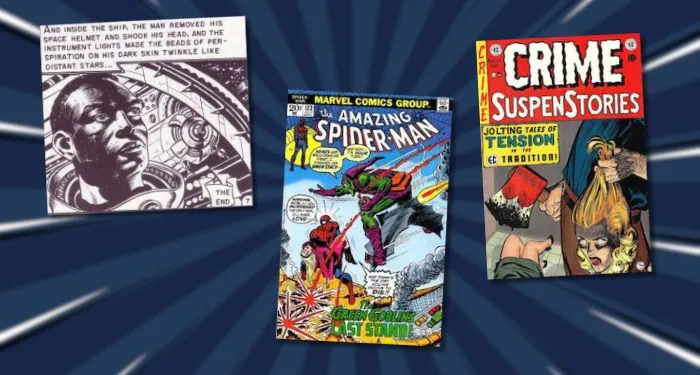

I kept being reminded of other novels while reading this one—the fateful encounters on the emigrant ship recall George Lamming’s 1954 novel The Emigrants, about Jamaican newcomers to Britain; Zoe’s struggles with her identity echo passages from Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook (1962); and the encounters forced on characters by their shared housing recall the London lodging house novels of the early 1960s by Lynne Reid Banks, Alexander Baron, and Sam Selvon. But The Edge of the Alphabet isn’t really like any of those books.

Although it appears to continue the stories of the characters in Owls Do Cry it could hardly be called a sequel, since it decisively rejects the first novel’s broadly realist narrative style. All the main characters live “at the edge of the alphabet,” where “words crumble and all forms of communication between the living are useless.” They cannot connect with one another through speech, but there is a fourth character—the novel’s narrator, Thora Pattern (an obvious play on Frame)—who holds their isolated worlds together. Like the rest of the company, Pattern is hopelessly alone, unsure of herself, and of a morbid cast of mind: “Call my longing in question yet I dream of people. I, Thora Pattern, dream of all people who turn in their sleep and moan, apprehensive of death.”

Toby, Pat, and Zoe are dreamed by the mind of Thora Pattern, and in turn Pattern’s mind is deeply influenced by Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus (1923)—at one point Toby is renamed Orpheus. They occasionally become alert to the fact that they are mere playthings of their creator. “Am I fiction, then?” asks Toby. Frame’s exploration of shared mental states in the midst of extreme isolation may owe something to her reading of Jung (she had briefly been in therapy with an analyst who had trained with Jung in Zurich, and this analyst had introduced her to Rilke), but it also echoes the metafictional games of Muriel Spark’s The Comforters and Evelyn Waugh’s The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold, both of which were published in 1957. Like Caroline Rose in Spark’s novel, and like Pinfold, Frame’s characters overhear themselves being typed into existence. Unlike Waugh and Spark, however, Frame writes a story that is relentlessly bleak, and full of unearned rhetorical flourishes:

Now I, Thora Pattern (who live at the edge of the alphabet where words like plants either grow poisonous tall and hollow about the rusted knives and empty drums of meaning, or, like people exposed to a deathly weather, shed their fleshy confusion and show luminous, knitted with force and permanence), now I walk day and night among the leavings of people, places and moments. Here the dead (my goldsmiths) keep cropping up like daisies with their floral blackmail. It is nearly impossible to bribe them or buy their silence. They are never finished with trinkets pockets lockets gold watches that swing on giant chains against their dust-filled hearts. They leave their marks like fly-specks upon my life. Why do they spatter my vision with the excrement of the past, buzz in my head, seek the snow-crystals of desire?

It’s not fair to criticize a book for being no fun when that clearly wasn’t the aim. The Edge of the Alphabet wants to give voice to the “life within,” but the pattern fails to cohere, and we are left with vague statements about meaning, creation, and death. It’s a far cry from Faces in the Water or the limpid prose of the autobiography. Writing may have saved Frame’s life because fiction allowed her to unmute herself and express her isolated inner world. There is no secret ingredient forcing us to believe her stories. They ask us only to recognize that they were real for her.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·